Surgery is almost always performed, regardless of age, in order to:[3]Van Effenterre R, Boch AL. Craniopharyngioma in adults and children: a study of 122 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 2002 Jul;97(1):3-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12134929?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Garre ML, Cama A. Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007 Aug;19(4):471-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17630614?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Puget S, Garnett M, Wray A, et al. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. J Neurosurg. 2007 Jan;106(1 suppl):3-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17233305?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Fischer EG, Welch K, Shillito J, et al. Craniopharyngiomas in children. Long-term effects of conservative surgical procedures combined with radiation therapy. J Neurosurg. 1990 Oct;73(4):534-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2398383?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al. Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012 Oct;10(4):293-301.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22920295?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Hankinson TC, Palmeri NO, Williams SA, et al. Patterns of care for craniopharyngioma: survey of members of the american association of neurological surgeons. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49(3):131-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24577430?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Mortini P, Losa M, Pozzobon G, et al. Neurosurgical treatment of craniopharyngioma in adults and children: early and long-term results in a large case series. J Neurosurg. 2011 May;114(5):1350-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21214336?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgery relieves raised intracranial pressure, and prevents progressive worsening of presenting symptoms or development of new symptoms.

Surgery may include biopsy only, cyst aspiration, or tumour resection (either partial or complete). Surgery can also include placement of a CSF diverting shunt to treat any associated hydrocephalus. This may follow placement of a temporary external ventricular drain for management of acute hydrocephalus. On occasion, high-dose intravenous corticosteroids can be used to treat any associated peri-tumoural oedema.

Contrast-enhanced brain imaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]/computed tomography [CT]) helps determine the surgical approach and provides a baseline for evaluating residual disease and response to treatment.

Baseline endocrine and ophthalmological evaluations with appropriate consultations must be performed to aid in monitoring effects of surgery upon endocrine function.[7]Defoort-Dhellemmes S, Moritz F, Bouacha I, et al. Craniopharyngioma: ophthalmological aspects at diagnosis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):321-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700306?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Halac I, Zimmerman D. Endocrine manifestations of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005 Aug;21(8-9):640-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16047216?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Hopper N, Albanese A, Ghirardello S, et al. The preoperative endocrine assessment of craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):325-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700307?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Sorva R, Heiskanen O, Perheetupa J. Craniopharyngioma surgery in children: endocrine and visual outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988 Apr;4(2):97-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3401877?tool=bestpractice.com

If high-dose intravenous corticosteroids are started for peri-tumoural oedema, they should be tapered to oral hydrocortisone or the patient evaluated for adrenal insufficiency once treatment with high-dose corticosteroids has been stopped.[35]Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Craniopharyngioma: Guidelines for the management of children and young people (CYP) aged up to 19 years. Oct 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.cclg.org.uk/sites/default/files/2025-03/craniopharyngioma-oct21.pdf

Following primary surgery, radiotherapy may be required for any residuals.[36]Stripp DC, Maity A, Janss AJ, et al. Surgery with or without radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngiomas in children and young adults. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004 Mar 1;58(3):714-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14967425?tool=bestpractice.com

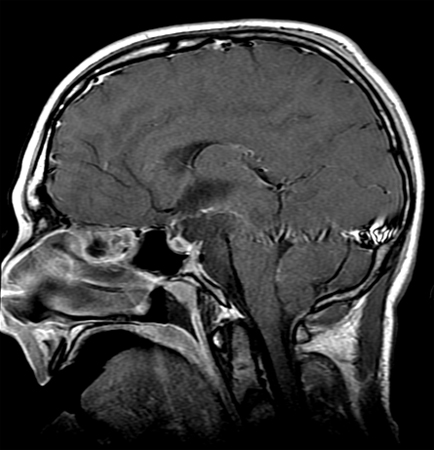

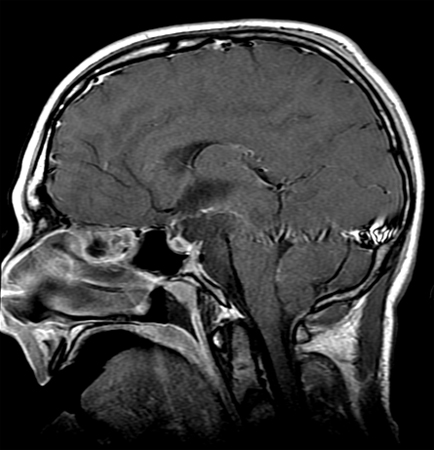

As endocrinopathies are common (both pre- and postoperatively), hormone replacement therapy is usually necessary, depending upon the specific endocrine deficiencies.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: sagittal post-contrast MRIFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma (postoperative): sagittal post-contrast MRIFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma (postoperative): sagittal post-contrast MRIFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

Surgery

The extent of surgical resection and the potential risks of surgery depend on tumour size and location.[11]Dhellemmes P, Vinchon M. Radical resection for craniopharyngiomas in children: surgical technique and clinical results. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700308?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Puget S, Garnett M, Wray A, et al. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. J Neurosurg. 2007 Jan;106(1 suppl):3-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17233305?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al. Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012 Oct;10(4):293-301.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22920295?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Raper DM, et al. Endoscopic skull base surgery: a comprehensive comparison with open transcranial approaches. Br J Neurosurg. 2012 Oct;26(5):637-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22324437?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Hoffman HJ, De Silva M, Humphreys RP, et al. Aggressive surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1992 Jan;76(1):47-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1727168?tool=bestpractice.com

Gross total resection should be achieved if possible; however, while maximising resection, long-term side effects should also be minimised, bearing in mind the availability of adjuvant radiotherapy for subtotally resected lesions.

When adherent to nearby structures, such as the basilar artery, hypothalamus, or optic chiasm, surgery may be limited. In these cases, tissue biopsy for diagnosis and decompression of important anatomical structures is often attempted, without complete resection. Caution is required if intracystic therapies are used, as leakage carries toxicity to the optic structures and perforator vessels.

Surgical approach

Depends upon the anatomy (relationship to the sella, optic chiasm, and third ventricle) and size of the tumour as determined preoperatively by cranial MRI.[29]Curran JG, O'Connor E. Imaging of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005 Aug;21(8-9):635-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16078078?tool=bestpractice.com

A number of surgical approaches may be used:[39]Fong RP, Babu CS, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic endonasal approach for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg Sci. 2021 Apr;65(2):133-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33890754?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Soldozy S, Yeghyayan M, Yağmurlu K, et al. Endoscopic endonasal surgery outcomes for pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2020 Jan 1;48(1):E6.

https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/48/1/article-pE6.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31896083?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Palmisciano P, Young K, Ogasawara M, et al. Craniopharyngiomas invading the ventricular system: a systematic review. Anticancer Res. 2022 Sep;42(9):4189-97.

https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/42/9/4189.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36039438?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Cossu G, Jouanneau E, Cavallo LM, et al. Surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in adult patients: a systematic review and consensus statement on behalf of the EANS skull base section. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020 May;162(5):1159-77.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32112169?tool=bestpractice.com

Transcortical or transcallosal approaches allow a transventricular (from above) approach, which is indicated for tumours that involve the third ventricle and are above the optic chiasm.

Sub-frontal translamina terminalis approach is indicated for tumours located anterior to the optic chiasm or in the anterior third ventricle.

Pterional trans-sylvian approach. It can be combined with an orbito-zygomatic approach and translamina terminalis depending on tumour extent and location.

Microscopic trans-sphenoidal approach (either transnasal or sub-labial) is utilised if the tumour is totally intrasellar (pituitary fossa).

Extended endoscopic endonasal surgery is increasingly used given the ability to directly visualise the tumour relationship to critical structures such as the optic chiasm, pituitary gland etc. It is associated with decreased risk of hypothalamic injury and higher chance of gross total resection.

For large multi-compartmental tumours, a combined approach using two or more of these options may be used either in combination or a staged fashion.[11]Dhellemmes P, Vinchon M. Radical resection for craniopharyngiomas in children: surgical technique and clinical results. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):329-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700308?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Hoffman HJ, De Silva M, Humphreys RP, et al. Aggressive surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1992 Jan;76(1):47-52.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1727168?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical complications include risk of arterial injury (anterior cerebral arteries, carotid and the basilar artery) with resulting strokes, pituitary dysfunction, arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D; previously known as diabetes insipidus), visual loss, and hypothalamic dysfunction. A higher incidence of hormone deficiency has been reported among paediatric patients undergoing complete resection compared with those managed with conservative surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy.[43]Tan TSE, Patel L, Gopal-Kothandapani JS, et al. The neuroendocrine sequelae of paediatric craniopharyngioma: a 40-year meta-data analysis of 185 cases from three UK centres. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Mar;176(3):359-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28073908?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al. A systematic review of the results of surgery and radiotherapy on tumor control for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Feb;29(2):231-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23089933?tool=bestpractice.com

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is typically used in the treatment of patients who have had either surgical biopsy or incompletely resected tumours.[44]Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al. A systematic review of the results of surgery and radiotherapy on tumor control for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Feb;29(2):231-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23089933?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Weiss M, Sutton L, Marcial V, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of childhood craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989 Dec;17(6):1313-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2689398?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Habrand JL, Ganry O, Couanet D, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngioma: a 25-year experience and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 May 1;44(2):255-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10760417?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Varlotto JM, Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, et al. External beam irradiation of craniopharyngioma: long-term analysis of tumor control and morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Oct 1;54(2):492-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12243827?tool=bestpractice.com

Although complete resection remains the mainstay for select patients, data from retrospective studies suggest that long-term outcomes with subtotal resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy continue to improve and that subtotal resection without adjuvant radiation was an independent risk factor for tumour recurrence/progression.[16]Zacharia BE, Bruce SS, Goldstein H, et al. Incidence, treatment and survival of patients with craniopharyngioma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Neuro Oncol. 2012 Aug;14(8):1070-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22735773?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al. Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2010 Apr;28(4):E5.

https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/28/4/article-pE5.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20367362?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Fouda MA, Karsten M, Staffa SJ, et al. Management strategies for recurrent pediatric craniopharyngioma: new recommendations. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2021 May 1;27(5):548-55.

https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/27/5/article-p548.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33668031?tool=bestpractice.com

The optimum timing of radiotherapy in children remains uncertain, and due to the cognitive risks of administering radiotherapy to young children, delaying until there is evidence of progression may be preferable in selected individuals.[26]Gan HW, Morillon P, Albanese A, et al. National UK guidelines for the management of paediatric craniopharyngioma. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023 Sep;11(9):694-706.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37549682?tool=bestpractice.com

Advances in radiotherapy techniques have made this option more effective and safe, and definitive radiotherapy may be an option in some patients. Whilst this remains controversial, observational data suggest that outcomes with definitive radiotherapy (radiotherapy alone) are comparable to those of established craniopharyngioma treatment modalities.[50]Hill TK, Baine MJ, Verma V, et al. Patterns of care in pediatric craniopharyngioma: outcomes following definitive radiotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2019 Feb;39(2):803-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30711960?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Zhang C, Verma V, Lyden ER, et al. The role of definitive radiotherapy in craniopharyngioma: a SEER analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug;41(8):807-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28263230?tool=bestpractice.com

Head-to-head prospective studies are required.

Modality

The radiotherapy technique used (conventional fractionated external beam radiation, conformal external beam radiation; or advanced techniques including intensity-modulated radiation, stereotactic radiosurgery, and proton beam therapy) is dependent upon patient and tumour factors including patient age and preference, prior treatment for craniopharyngioma, the size of the residual tumour, its anatomic relationship to surrounding neural structures (in particular, the optic nerve and chiasm), and availability. Conventional fractionated external-beam radiotherapy (photon-based) administered daily for 5-6 weeks with a median tumour dose of 54 Gy is considered the standard of care for most tumours.[46]Habrand JL, Ganry O, Couanet D, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngioma: a 25-year experience and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 May 1;44(2):255-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10760417?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Varlotto JM, Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, et al. External beam irradiation of craniopharyngioma: long-term analysis of tumor control and morbidity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Oct 1;54(2):492-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12243827?tool=bestpractice.com

Where available and suitable, precision modalities (e.g., proton beam therapy, fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy) seem to be associated with higher rates of tumour control.[52]Harary PM, Rajaram S, Hori YS, et al. The spectrum of radiation therapy options for craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2025 Jun;173(2):275-88.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40063185?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Jalali R, Ghosh S, Chatterjee A, et al. High-precision radiotherapy achieves excellent long-term control and preserves function in pediatric craniopharyngioma-Subset analysis of a randomized trial. Neuro Oncol. 2025 Sep 17;27(8):2147-57.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40056158?tool=bestpractice.com

Stereotactic radiosurgery involves the delivery of a single large fraction, or several fractions, of radiation dosage, either via a linear accelerator (LINAC) or as multiple cobalt beams (Gamma Knife). Limited studies exist, although experience with other extra-axial intracranial tumours (e.g., meningiomas) suggests this is credible and effective therapy. The application of stereotactic radiosurgery is limited by tumour location in relation to the optic chiasm and nerve, and tumour size and geometry. The technique is best suited for the treatment of small (<2 cm), spherical tumours, or low-volume residual disease.[46]Habrand JL, Ganry O, Couanet D, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of craniopharyngioma: a 25-year experience and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999 May 1;44(2):255-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10760417?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Niranjan A, Kano H, Mathieu D, et al. Radiosurgery for craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Sep 1;78(1):64-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20005637?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Chung WY, Pan DH, Shiau CY, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000 Dec;93(suppl 3):47-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11143262?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Scarzello G, Buzzaccarini MS, Perilongo G, et al. Acute and late morbidity after limited resection and focal radiation therapy in craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19 Suppl 1:399-405.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700317?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Minniti G, Saran F, Traish D, et al. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy following conservative surgery in the control of craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol. 2007 Jan;82(1):90-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17161483?tool=bestpractice.com

Radiotherapy in many instances will result in hypopituitarism and consequently the need for hormone replacement therapy.[25]Sorva R, Heiskanen O, Perheetupa J. Craniopharyngioma surgery in children: endocrine and visual outcome. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988 Apr;4(2):97-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3401877?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Scarzello G, Buzzaccarini MS, Perilongo G, et al. Acute and late morbidity after limited resection and focal radiation therapy in craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19 Suppl 1:399-405.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700317?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Müller HL. Consequences of craniopharyngioma surgery in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;96(7):1981-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21508127?tool=bestpractice.com

Other possible complications include loss of vision (secondary to a radiation-induced optic neuropathy), rarely radiation injury/necrosis of the anterior temporal lobes, radiation injury to the hypothalamus, and induction of neurocognitive deficits.[59]Poretti A, Grotzer MA, Ribi K, et al. Outcome of craniopharyngioma in children: long-term complications and quality of life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004 Apr;46(4):220-9.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00476.x/pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15077699?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Kiehna EN, Mulhem RK, Li C, et al. Changes in attentional performance of children and young adults with localized primary brain tumors after conformal radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Nov 20;24(33):5283-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17114662?tool=bestpractice.com

Endocrine therapy

Endocrine replacement therapy depends upon the specific endocrine deficiency.[5]Karavitaki N, Cudlip S, Adams CB, et al. Craniopharyngiomas. Endocr Rev. 2006 Jun;27(4):371-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16543382?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Halac I, Zimmerman D. Endocrine manifestations of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005 Aug;21(8-9):640-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16047216?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Hopper N, Albanese A, Ghirardello S, et al. The preoperative endocrine assessment of craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):325-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700307?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Garre ML, Cama A. Craniopharyngioma: modern concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007 Aug;19(4):471-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17630614?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Müller HL. Consequences of craniopharyngioma surgery in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;96(7):1981-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21508127?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Müller HL, Gebhardt U, Teske C, et al. Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after three year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Jul;165(1):17-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21490122?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Jul 1;56(7):1120-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21488157?tool=bestpractice.com

No improvement is seen in baseline endocrine dysfunction following surgery (with the possible exception of hyperprolactinaemia). Indeed, the incidence increases following therapy as a consequence of surgery (lowest risk with trans-sphenoidal surgery).

Approximate prevalence of specific deficiencies includes growth hormone (75%), hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (75%), adrenocorticotrophic hormone deficiency (25%), hypothyroidism (25%), and AVP-D (>70% in children; 50% in adults).[5]Karavitaki N, Cudlip S, Adams CB, et al. Craniopharyngiomas. Endocr Rev. 2006 Jun;27(4):371-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16543382?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Halac I, Zimmerman D. Endocrine manifestations of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005 Aug;21(8-9):640-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16047216?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Hopper N, Albanese A, Ghirardello S, et al. The preoperative endocrine assessment of craniopharyngiomas. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Apr;19(suppl 1):325-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16700307?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Müller HL, Gebhardt U, Teske C, et al. Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after three year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Jul;165(1):17-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21490122?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Jul 1;56(7):1120-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21488157?tool=bestpractice.com

See Hypopituitarism.

Management of recurrent/refractory disease

Recurrent or treatment refractory disease is established both clinically and radiographically. If present, repeat surgery may be indicated.[49]Fouda MA, Karsten M, Staffa SJ, et al. Management strategies for recurrent pediatric craniopharyngioma: new recommendations. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2021 May 1;27(5):548-55.

https://thejns.org/pediatrics/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/27/5/article-p548.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33668031?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Liubinas SV, Munshey AS, Kaye AH. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011 Apr;18(4):451-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21316970?tool=bestpractice.com

Radiotherapy may be used to treat recurrence, and observational data suggest that stereotactic radiosurgery is an effective, minimally invasive option in this context.[54]Niranjan A, Kano H, Mathieu D, et al. Radiosurgery for craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Sep 1;78(1):64-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20005637?tool=bestpractice.com

Recurrences may manifest as a recalcitrant tumour cyst requiring surgical drainage (aspiration) and sometimes placement of an intratumoural cyst catheter and sub-galeal reservoir. This allows repeated fluid aspiration and, if necessary, instillation of intracavitary radioactive colloidal phosphorus/yttrium.[64]Julow J, Backlund E-O, Lanyi F, et al. Long-term results and late complications after intracavitary yttrium-90 colloid irradiation of recurrent cystic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007 Aug;61(2):288-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17762741?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Van den Berg JH, Blaauw G, Breeman WA, et al. Intracavitary brachytherapy of cystic craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 1992 Oct;77(4):545-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1527612?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Pollack IF, Lunsford LD, Slamovits TI, et al. Stereotaxic intracavitary irradiation for cystic craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg. 1988 Feb;68(2):227-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3276836?tool=bestpractice.com

Alternatively, chemotherapy agents may be placed; a variety of drugs have been utilised, including bleomycin, methotrexate, and cytarabine.[67]Zhang S, Fang Y, Cai BW, et al. Intracystic bleomycin for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jul 14;7:CD008890.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6457977

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27416004?tool=bestpractice.com

Intracystic chemotherapy may be considered in a research setting for persistent tumours despite other therapies, but it is not a first-line treatment option.

Caution is required if intracystic therapies are used, as leakage carries toxicity to the optic structures and perforator vessels.

In exceptional instances (e.g., tumour still present despite prior surgery/radiotherapy and no longer operable), patients may be treated with systemic chemotherapy.[63]Liubinas SV, Munshey AS, Kaye AH. Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011 Apr;18(4):451-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21316970?tool=bestpractice.com

However, data for chemotherapy in refractory craniopharyngioma are limited, and there is no standard systemic regimen.

Long-term sequelae

In addition to immediate management of the craniopharyngioma and endocrine deficiencies, the detection and management of the potential longer-term sequelae (such as delayed optic atrophy, hypopituitarism, obesity, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes mellitus) is essential, particularly in children.[58]Müller HL. Consequences of craniopharyngioma surgery in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;96(7):1981-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21508127?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Sahakitrungruang T, Klomchan T, Supornsilchai V, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and insulin dynamics in children after craniopharyngioma surgery. Eur J Pediatr. 2011 Jun;170(6):763-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21107605?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A, et al. Long-term outcomes and complications in patients with craniopharyngioma: the British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014 Apr 1;88(5):1011-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24661653?tool=bestpractice.com

Quality of life is significantly impacted. Craniopharyngioma is best thought of as a chronic disease that is multi-dimensional.[70]Müller HL. Childhood craniopharyngioma. Pituitary. 2013 Mar;16(1):56-67.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22678820?tool=bestpractice.com

Additionally, adults with craniopharyngioma have a substantially elevated risk of cardiovascular disease relative to the general population, added to the reduced health already common to these patients.[71]Erfurth EM. Endocrine aspects and sequel in patients with craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jan;28(1-2):19-26.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25514328?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma (postoperative): sagittal post-contrast MRIFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma (postoperative): sagittal post-contrast MRIFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].