Aetiology

The aetiology of craniopharyngioma is unknown at present, and the pathogenesis is not completely understood. The tumour epithelium is thought to originate in either of two ways: from embryological remnants or by metaplasia of mature tissues.[5][12][18]

The most common histological form of craniopharyngioma, the adamantinomatous variant (present in nearly all childhood instances and the majority of those in adults), is thought to arise from neoplastic transformation of embryonic remnant squamous cell nests of the involuted craniopharyngeal duct (which in cranial development initially connects Rathke's pouch with the stomodeum).[5][12][18] During the process of growth and rotation of Rathke's pouch, leading to formation of the anterior pituitary, these cell remnants remain throughout the sellar region, extending superiorly to the median eminence. Their proliferation results in tumour formation.

The metaplastic hypothesis suggests that the squamous papillary variant (15% of all adult craniopharyngiomas) arises as a result of metaplasia of the adenohypophyseal cells in the pars tuberalis with formation of squamous cell nests.[5][12][18] On a molecular basis, the adamantinomatous variant has a dysregulated Wnt signalling pathway with excess beta-catenin accumulation.[19] As beta-catenin-mediated Wnt signalling regulates cellular proliferation, morphology, and development, mutations in genes encoding beta-catenin (e.g., CTNNB and APC) may play a role in tumour initiation and growth.

The squamous papillary variant does not show evidence of accumulation of beta-catenin and dysregulated Wnt signalling. However, several studies have shown the presence of activating mutations in the BRAF gene in the squamous papillary type.[20]

Pathophysiology

Both the embryonic and metaplastic modes of craniopharyngioma pathogenesis explain the intracranial topography (sellar, infra- or suprachiasmatic) of the tumour. This in turn provides an explanation for how these tumours present (intracranial hypertension, visual loss, or endocrinological dysfunction), and the characteristic cranial imaging findings.

The specific size and location of the tumour (sellar, extrasellar, above or below, in front of or behind the optic chiasm) dictate the surgical approach and adjuvant surgical procedures (cyst aspiration, cerebrospinal fluid shunting).[4][5][6][21] As craniopharyngiomas are often intimately attached to the hypothalamus, and optic apparatus, postoperative morbidity may develop.

Classification

Pathological classification[1]

Craniopharyngiomas are divided into two histopathological tumour types, both classed as grade 1 tumours by the World Health Organization.[2]

Adamantinous type (>80% of tumours):

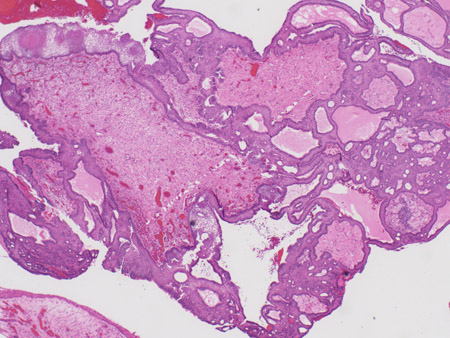

Adamantinous epithelium, with calcification, keratin nodule formation; often poorly demarcated from brain. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: adamantinous histology (low power) with complex arrangements of epithelium, cysts, and gliotic brainFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

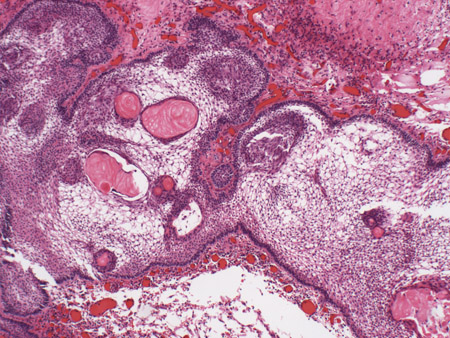

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: adamantinous histology (medium power) with epithelial ribbons showing reticular areas and nodules of keratinFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

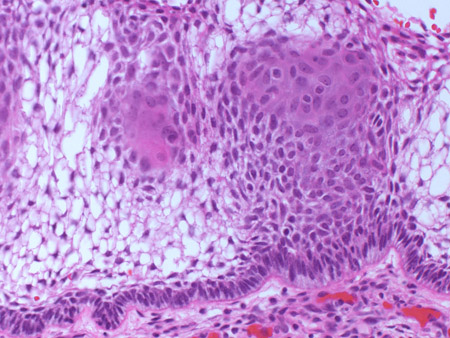

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: adamantinous histology (medium power) with epithelial ribbons showing reticular areas and nodules of keratinFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: adamantinous histology (high power) with basal-aligned columnar cells, stellate reticulum, and epithelial keratinisationFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Craniopharyngioma: adamantinous histology (high power) with basal-aligned columnar cells, stellate reticulum, and epithelial keratinisationFrom the collection of Marc C. Chamberlain [Citation ends].

Squamous papillary type (<20% of tumours):

Squamous epithelium, with squamous papillary formations; well demarcated from brain; occur mostly in adults.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer