Aetiology

The primary aetiological factor involved in Barrett's oesophagus is gastro-oesophageal reflux. However, there is evidence that combined acid and bile reflux are the primary causative agents. In one study of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, more than 50% had abnormal levels of bile in the oesophagus.[12] The highest level of oesophageal bile was in patients with Barrett's oesophagus, and about one half of patients with Barrett's oesophagus with abnormal oesophageal bile exposure had normal bile levels in the stomach. Barrett's oesophagus, and oesophageal mucosal injury overall, was most common in patients exposed to a combination of acid and bile, and uncommon in patients exposed only to bile. Mucosal injury was less common in those exposed to acid alone, but still significantly higher than normal.[13]

Pathophysiology

The American College of Gastroenterology defines Barrett's oesophagus as a change in the oesophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognised at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular oesophagus and excludes intestinal metaplasia of the cardia.[14] However, not all intestinal metaplasia is endoscopically visible. Non-goblet epithelium can be intestinalised.[15] Gradually we are are developing a better understanding of the complex molecular mechanisms that are implicated in the conversion of normal squamous oesophageal epithelium to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma.[16]

For Barrett's oesophagus to develop, environmental factors must interact with genetically determined characteristics. Because Barrett's oesophagus is rarely familial (although there are some 'multiplex' families with Barrett's oesophagus which places them at substantial risk of adenocarcinoma) it is likely that these characteristics are normal variations (polymorphism), rather than a single gene mutation.[17]

The more commonly accepted pathogenetic mechanism involves metaplastic columnar stem cell development from a local (squamous epithelium stem cell) or bone marrow (bone marrow derived stem cell) source. The stem cell origin of Barrett's oesophagus can explain its persistence and the predisposition to developing adenocarcinoma. The proposed origins of these altered metaplastic stem cells are:

the basal cell layer of the squamous epithelium

stem cells originating from the gastro-oesophageal junction proliferating in response to acid and duodeno-gastro-oesophageal reflux

stem cells from the neck of the oesophageal sub-mucosal glands migrating to, and proliferating in, the surface of the distal oesophagus after squamous mucosa injury

bone marrow stem cell migration to the injured epithelium.

These changes may be mediated by activation or inactivation of transcription factors and modulation of signalling pathways at the cellular level. Gastro-oesophageal reflux can produce genetic alterations, which result in increased production of transcription factors promoting intestinal cell differentiation (metaplasia) and decreased production of transcription factors promoting squamous cell differentiation.[18]

There are several candidate genes whose alteration may lead to development of intestinal metaplasia.[19] Expression of the cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene in the oesophageal squamous epithelium seems to be increased as a result of reflux, and down-regulated as a result of anti-reflux surgery.[20] In addition, the homoeotic transcription factor Cdx2 (Caudal-type homeobox 2) has been discovered to be the 'master switch' gene for intestinal epithelium. Its loss or deletion is associated with the development of metaplasia.[21]

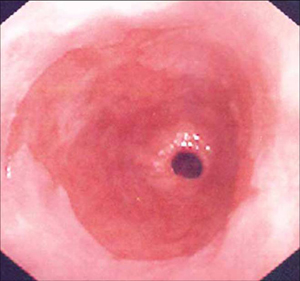

Ultimately, the importance of intestinal metaplasia is in its malignant potential. Although the exact genetic and molecular mechanisms have not been elucidated, it seems that the intraluminal refluxate acts as a pro-proliferative driver leading to the genetic and, more important, biological characteristics of malignancy. These include activation of cell surface pH controllers (e.g., sodium-hydrogen exchangers), which lead to cell signalling changes (e.g., transforming growth factor-beta, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and protein kinase C), resulting in disruption of the p53 gene, leading to evasion of apoptosis. These hyper-proliferating cells will eventually require angiogenesis to maintain growth. This is usually mediated by the cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene. Eventually, it is hoped that an understanding of the molecular events that occur in the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence will lead to biomarkers to identify patients who are destined to develop adenocarcinoma.[19] Although it is clear that Barrett’s oesophagus increases the risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, quantifying the risk has been difficult. One systematic review set the risk as 6.3/1000 person-years, with a 95% confidence interval of 4.7 to 8.4/1000 people and substantial heterogeneity of the data.[22][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's oesophagus; note salmon-coloured mucosa extending superior to the gastro-oesophageal junction as a continuous columnFrom the personal collection of Dr Vic Velanovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's oesophagus; note salmon-coloured mucosa extending superior to the gastro-oesophageal junction with marked irregular borderFrom the personal collection of Dr Vic Velanovich; used with permission [Citation ends].

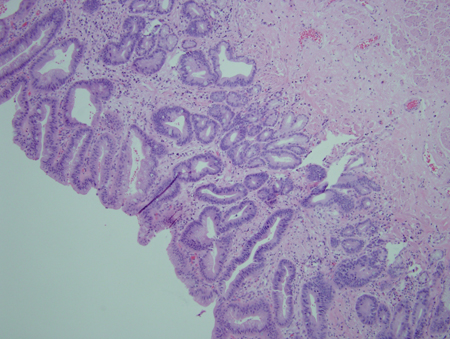

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's oesophagus; note salmon-coloured mucosa extending superior to the gastro-oesophageal junction with marked irregular borderFrom the personal collection of Dr Vic Velanovich; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia without dysplasia, demonstrating columnar epithelium with goblet cells from superior to the gastro-oesophageal junctionCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends].

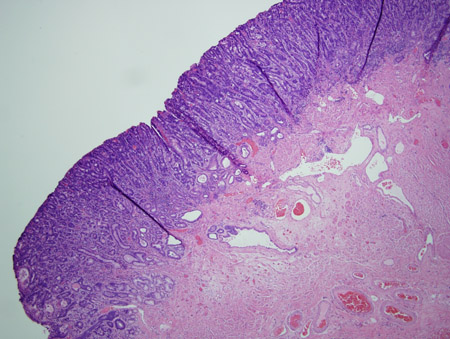

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia without dysplasia, demonstrating columnar epithelium with goblet cells from superior to the gastro-oesophageal junctionCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with low-grade dysplasia; note the more irregular cells and nucleiCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with low-grade dysplasia; note the more irregular cells and nucleiCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with high-grade dysplasia; note more advanced irregularity of the cellsCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with high-grade dysplasia; note more advanced irregularity of the cellsCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with high-grade dysplasia associated with a focus of intramucosal carcinoma; note the frankly malignant cells beyond the confines of the basement membrane to involve the lamina propriaCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Barrett's metaplasia with high-grade dysplasia associated with a focus of intramucosal carcinoma; note the frankly malignant cells beyond the confines of the basement membrane to involve the lamina propriaCourtesy of Adrian Ormsby, MD, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer