Approach

A directed history and dilated fundus examination are typically sufficient to diagnose age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Prognosis and treatment are dependent on the type of AMD and severity of disease. Ancillary studies may be used as indicated to differentiate type and severity of disease and to plan treatment strategies.

Clinical evaluation

In the early stages of the disease, patients may have no history of visual complaints or very mild distortion of vision.[28] Other symptoms include micropsia, metamorphopsia, decreased vision, scotoma, photopsia, and difficulties with dark adaptation.[4][39][40] Patients may experience difficulty with daily activities such as driving and reading, especially in dim lighting.[41][42]

A patient presenting with the neovascular form of the disease may report a rapid-onset central distortion or scotoma in one eye.[41]

In geographic atrophy, patients may present with slow, progressive loss of central vision.[41]

Key components of the directed history are age and smoking history.[4] A family history of AMD may suggest a genetic predisposition.[39][40]

Ophthalmic examination

Both eyes are examined for signs of disease because AMD is often bilateral. Initial and follow-up examination comprises a comprehensive eye examination, Amsler grid examination, and stereo biomicroscopic examination of the macula by slit-lamp.[4][40]

An Amsler grid examination of the involved eye may reveal a central area of distortion or scotoma.[42]

Dilated fundus examination

Dilated fundus examination identifies characteristics of disease and determines the stage of disease.

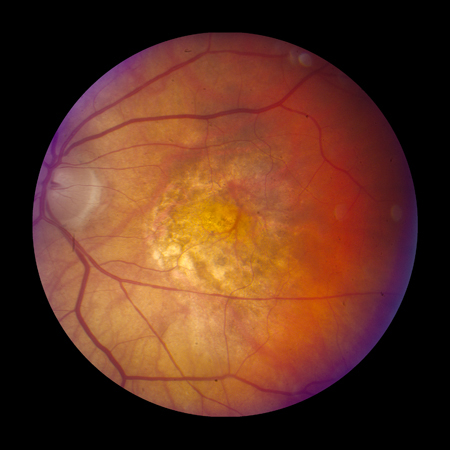

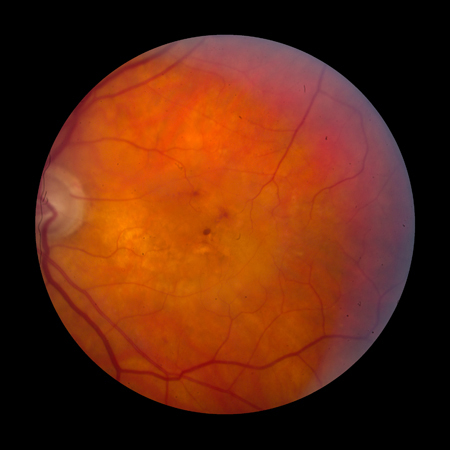

Patients in the early stages of disease will typically have intermediate-sized drusen. Patients with intermediate disease will typically have pigmentary changes, and medium and/or large drusen.[2][4][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Early AMD (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 2)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intermediate AMD (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 3)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intermediate AMD (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 3)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

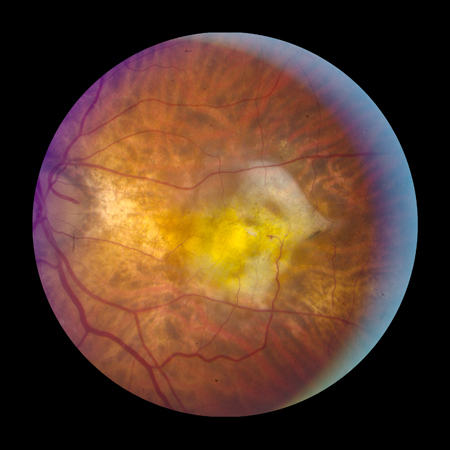

Late-stage disease is characterised by geographic atrophy and/or neovascular AMD. The signs of neovascular AMD include subretinal haemorrhage, retinal pigment epithelial detachment, retinal oedema, cysts, and lipid exudates. Long-standing neovascular disease can present with severe visual loss and a fibrovascular scar with or without subretinal fluid.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Late AMD with central geographic atrophy (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 4)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Late AMD with choroidal neovascularisation with exudation (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 4)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Late AMD with choroidal neovascularisation with exudation (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 4)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fibrovascular scar from end-stage AMD (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 4)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fibrovascular scar from end-stage AMD (Age-Related Eye Disease Study Group [AREDS] category 4)Reproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

Subretinal drusenoid deposits are small drusen-like deposits that form between the photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium. Subretinal drusenoid deposits have been associated with increased risk of progression to late AMD.[41]

Imaging

Various imaging modalities are available, but optical coherence tomography (OCT) is the most widely used for diagnosing and managing AMD.[41]

OCT

In most practice settings, it is routine to use OCT to detect subclinical disease in patients with AMD.[41]

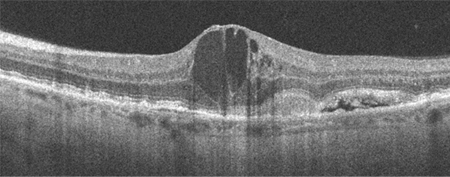

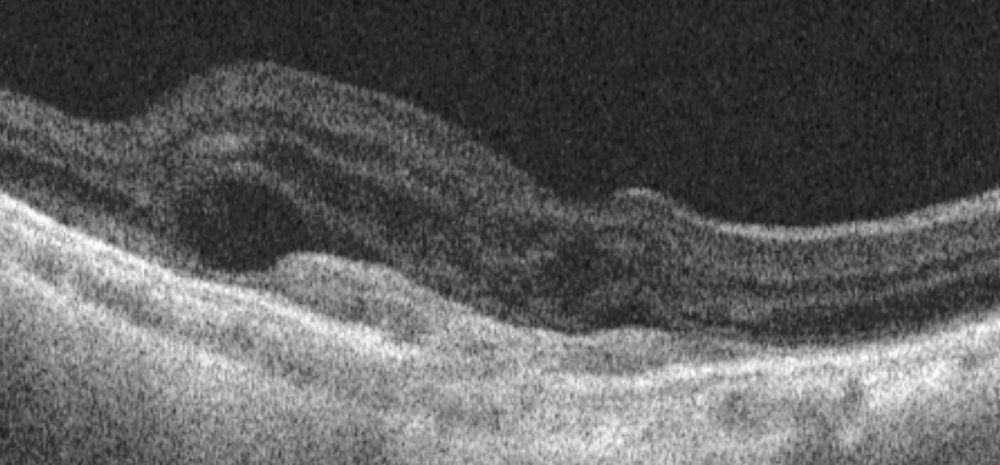

OCT can be used to test for or confirm the presence of subretinal or intraretinal fluid, the degree of retinal thickening (which may not be apparent on biomicroscopy alone), and, with OCT angiography, confirm the presence of macular neovascularisation (MNV), fibrosis and a hyper-reflective (fibrovascular) scar.[4][41][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High resolution optical coherence tomography image showing subretinal and intraretinal fluidReproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Optical coherence tomography image showing subretinal hyper-reflective lesion, and subretinal and intraretinal fluidFrom the collection of Sajjad Mahmood MA, MB BCHIR, FRCOphth; used with permission [Citation ends].

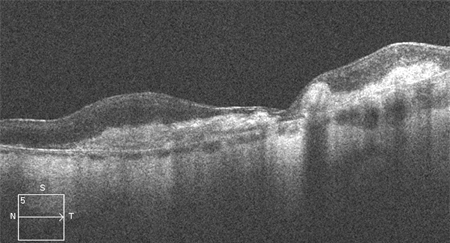

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Optical coherence tomography image showing subretinal hyper-reflective lesion, and subretinal and intraretinal fluidFrom the collection of Sajjad Mahmood MA, MB BCHIR, FRCOphth; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High resolution optical coherence tomography image showing hyper-reflective scarReproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High resolution optical coherence tomography image showing hyper-reflective scarReproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

Response to treatment can also be monitored using OCT. This can involve determining qualitative and quantitative changes in the volume of subretinal and intraretinal fluid before initiating treatment and over time in response to treatment.[43]

OCT angiography

OCT angiography detects blood flow using the change in OCT characteristics of the same area of retina over successive scans.[44] This can be used to image blood vessels and detect MNV in only a little more time than a standard OCT scan, and without the need for intravenous administration of fluorescein.[44][45] Active leak from vessels cannot be shown in the same way as fluorescein angiography, but if MNV is confirmed in conjunction with other signs of activity on the OCT scan, it may be sufficient to initiate therapy.[41][44][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Optical coherence tomography angiography image showing hyper-reflective lesion which corresponds with a network of choroidal neovascularisation; this has proliferated in between the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epitheliumFrom the collection of Sajjad Mahmood MA, MB BCHIR, FRCOphth; used with permission [Citation ends].

Fluorescein angiography

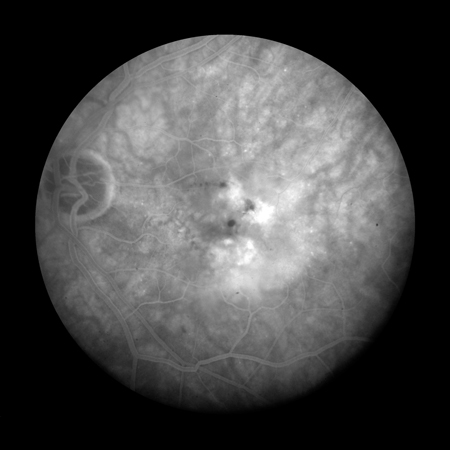

Fluorescein angiography is considered the definitive test for the confirmation of MNV and may be ordered if history and/or clinical examination or OCT suggests MNV.[4][41] It can be used to confirm that the blood vessels are actively leaking, as well as their anatomical location, and to measure the distance of MNV from the fovea. The result may assist in determining treatment; however, OCT angiography, when available, may be preferred in the first instance, and fluorescein angiography is not needed if sufficient information is available from structural OCT and/or OCT angiography.

Fluorescein angiography can be used to rule out the presence of active MNV, unless the MNV is blocked by haemorrhage.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fluorescein angiogram showing active choroidal neovascularisationReproduced from Scheie Eye Institute's patient image database; used with permission [Citation ends].

The presence of drusen (hyperfluorescence and hypofluorescence), geographic atrophy (transmission defects), and MNV (expanding hyperfluorescence) can be confirmed using fluorescein angiography. Fluorescein angiography may also assist in distinguishing between types of MNV.

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography

ICG angiography is usually considered an adjunctive or secondary test. ICG angiography allows a better visualisation of the deeper choroidal vessels and can help identify features of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, features of which may also be present in patients with neovascular AMD.[46] It can be used to detect type 3 MNV and may be helpful in situations where the source of leakage is obscured by subretinal haemorrhage, which makes interpretation of fluorescein studies difficult.[42]

Autofluorescence

Autofluorescence imaging is useful for delineating areas of geographic atrophy in dry AMD.[4][41] It can be used to detect drusen and subretinal drusenoid deposits. Autofluorescence can also be used to confirm lipofuscin deposition. This is referred to as ‘vitelliform deposition’ in the context of drusen and dry AMD, and is also a feature of adult vitelliform dystrophy (a condition that may be misdiagnosed as AMD).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer