Bladder cancer most commonly presents with haematuria (visible or non-visible).[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

Cancer-related haematuria is characteristically intermittent. Urological evaluation is required in all adults with visible haematuria and should be considered in adults with non-visible (microscopically confirmed) haematuria in the absence of a demonstrable benign cause.[58]Peterson LM, Reed HS. Hematuria. Prim Care. 2019 Jun;46(2):265-73.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095454319300119?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31030828?tool=bestpractice.com

Awaiting confirmation of non-visible haematuria on repeated samples (if potential precipitating causes have been excluded) before more extensive evaluation risks missing clinically significant cancers.[59]Jubber I, Shariat SF, Conroy S, et al. Non-visible haematuria for the detection of bladder, upper tract, and kidney cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2020 May;77(5):583-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791622?tool=bestpractice.com

All patients suspected of having bladder cancer require a thorough history and physical examination, although the examination is often unremarkable, particularly in patients with early disease.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

If Lynch syndrome is suspected (based on personal or family history, or presentation at young age), germline testing and genetic counselling should be considered.[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

See Screening.

Assessment of non-visible haematuria

Non-visible haematuria, defined as ≥3 red blood cells (RBCs) per high-power field, is a common presentation of bladder cancer.[59]Jubber I, Shariat SF, Conroy S, et al. Non-visible haematuria for the detection of bladder, upper tract, and kidney cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2020 May;77(5):583-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791622?tool=bestpractice.com

Threshold for evaluation with cystoscopy and imaging should be low in the absence of a clear cause and complete resolution of haematuria.

Risk stratification and risk-based evaluation are recommended; these are the same for patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy as for those who are not.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

The American Urological Association recommends evaluation according to risk of urological cancer.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

Low-risk patients meet all of the following criteria:

Women aged <60 years; men aged <40 years

Never smoker or <10 pack years

3-10 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

No risk factors for urothelial cancer

Intermediate-risk patients meet one or more of the following criteria:

Women aged ≥60 years; men aged 40-59 years

10-30 pack year smoking history

11-25 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

Previously low-risk patient with no prior evaluation and 3-25 RBC per high-power field on repeat urine microscopy

Any additional risk factor for urothelial cancer (additional risk factors include irritative lower urinary tract symptoms, prior pelvic radiotherapy, prior cyclophosphamide/ifosfamide chemotherapy, family history of urothelial cancer, family history of Lynch syndrome, occupational exposure to aromatic amines or benzene chemicals, chronic indwelling foreign body in the urinary tract).

High-risk patients meet one of more of the following criteria:

Men aged ≥60 years (women should not be categorised as high risk based on age alone)

>30 pack year smoking history

>25 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

History of visible haematuria

One or more additional risk factors for urothelial cancer (see above) plus any high-risk feature

For low-risk patients with non-visible haematuria, urine microscopy should be repeated within 6 months rather than performing immediate renal ultrasound or cystoscopy. If non-visible haematuria persists on repeat testing, the patient is reclassified as intermediate or high risk.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

Intermediate-risk patients should be offered renal ultrasound and cystoscopy.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

For select intermediate-risk patients who wish to avoid cystoscopy, urine cytology or a validated urine-based tumour marker assay may be considered to determine whether cystoscopy is required. Renal and bladder ultrasound should still be performed. If cystoscopy is not performed, urinalysis should be repeated within 12 months, with cystoscopy recommended if non-visible haematuria persists.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

High-risk patients should be offered cystoscopy and axial renal imaging, ideally with computed tomography (CT) urography.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

MR urography is an alternative if CT urography is contraindicated. Renal ultrasound with retrograde pyelogram is an option if CT and MRI are contraindicated. Ultrasound has the advantage of avoiding radiation exposure, but provides less detail than CT urogram.

Shared decision-making is recommended to determine follow-up for patients whose work-up produces a negative result. Most patients do not require ongoing monitoring or further evaluation, unless they have multiple risk factors, visible haematuria, or new or worsening urological symptoms. A positive repeat urinalysis should prompt shared decision-making regarding further evaluation.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

See Assessment of non-visible haematuria.

Assessment of visible haematuria

All patients with visible blood in the urine require investigation, even when related to over-anticoagulation. Complete spontaneous cessation of bleeding does not exclude the possibility of life-threatening malignancy.

Older patients with painless, visible haematuria should be considered at high risk for malignancy. Adults aged >45 years with unexplained visible haematuria (without urinary tract infection) should be referred for imaging and cystoscopy.[62]Ingelfinger JR. Hematuria in adults. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 8;385(2):153-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34233098?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. May 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

Evaluation of visible haematuria is based on the patient’s symptoms and clinical and laboratory findings. Urinalysis should be the initial test, followed by urine culture if infection is suspected.[62]Ingelfinger JR. Hematuria in adults. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 8;385(2):153-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34233098?tool=bestpractice.com

If dysmorphic red cells and casts are observed on microscopy, evaluation for glomerulopathy should be considered. The presence of crystals may suggest nephrolithiasis.[62]Ingelfinger JR. Hematuria in adults. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 8;385(2):153-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34233098?tool=bestpractice.com

If a transient cause is suspected, repeat urine microscopy should be carried out at a suitable interval.[64]O'Connor E, McVey A, Demkiw S, et al. Assessment and management of haematuria in the general practice setting. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021 Jul;50(7):467-71.

https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2021/july/haematuria-in-the-general-practice-setting

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34189542?tool=bestpractice.com

The presence of renal colic should prompt evaluation for nephrolithiasis; acute onset of frequency and dysuria should prompt urine culture (with antibiotic treatment if indicated).

Evaluation with cystoscopy and imaging with CT or magnetic resonance (MR) urography or renal ultrasound is required if other likely causes are excluded.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[65]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: hematuria. 2019 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69490/Narrative

See Assessment of visible haematuria.

Assessment of irritative voiding symptoms

Irritative voiding symptoms, including urgency, dysuria, and increased frequency, may occur, particularly in patients with CIS or high-grade bladder cancer.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

[50]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

However, the risk of bladder cancer in a patient presenting with irritative voiding symptoms in the absence of visible haematuria is low.[66]Schmidt-Hansen M, Berendse S, Hamilton W. The association between symptoms and bladder or renal tract cancer in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 Nov;65(640):e769-75.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4617272

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26500325?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Shephard EA, Stapley S, Neal RD, et al. Clinical features of bladder cancer in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 Sep;62(602):e598-604.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3426598

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22947580?tool=bestpractice.com

Common causes of dysuria (e.g., urinary tract infection, prostatitis) and urinary frequency (e.g., benign prostatic hypertrophy, overactive bladder) should be excluded. See Assessment of dysuria.

In patients being evaluated for bladder cancer, urine cytology may be useful as an adjunct to cystoscopy in patients with irritative voiding symptoms to help detect CIS or high-grade tumours.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

UK guidelines recommend an urgent specialist referral for patients aged ≥60 years who have unexplained non-visible haematuria and dysuria.[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. May 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

Cystoscopy and upper tract imaging

Cystoscopy is key to making the diagnosis.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

[50]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

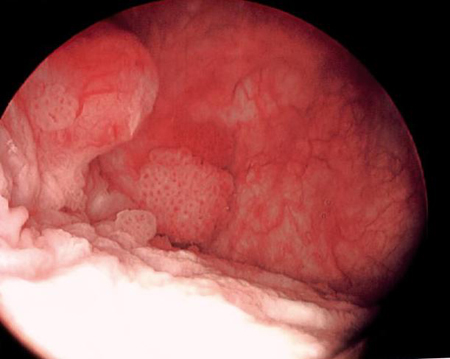

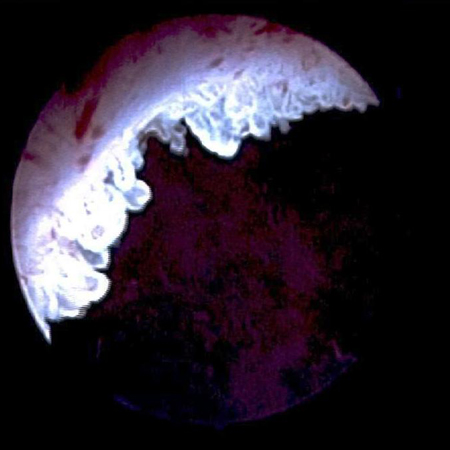

Direct visualisation of the bladder mucosa with a cystoscope allows identification of suspicious lesions. Low-grade tumours are papillary and easy to visualise, but high-grade tumours can be papillary, flat, or in situ and difficult to visualise with white light. Rough erythematous patches can be indicative of CIS, although the urothelium often appears normal.

Visualisation at cystoscopy may be improved by narrow-band imaging or blue light (fluorescence) cystoscopy in addition to white light; both appear to improve diagnostic accuracy compared with white light alone.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[68]Zheng C, Lv Y, Zhong Q, et al. Narrow band imaging diagnosis of bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2012 Dec;110(11 Pt B):E680-7.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11500.x/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22985502?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: a meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. Eur Urol. 2013 Nov;64(5):846-54.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0302283813003539?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23602406?tool=bestpractice.com

Random biopsies or biopsy of areas positive on blue light or narrow band cystoscopy may be needed to diagnose CIS.

Patients should be scheduled for transurethral resection of a bladder tumour (TURBT) if a lesion suspicious of a urothelial bladder tumour is identified at cystoscopy.

All patients with suspicious lesions detected at cystoscopy should undergo imaging of the upper tract collecting system if they have not already done so. This serves to identify nodal metastasis and obstruction (hydronephrosis).[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

CT urography, which images the urinary tract with contrast during the excretory phase, is the preferred modality.

MR urography is an alternative if CT urography is contraindicated. Renal ultrasound with retrograde pyelogram is an alternative for patients in whom CT and MRI are contraindicated.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Imaging may be obtained before or after resection; National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend CT or MRI before resection if possible.[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

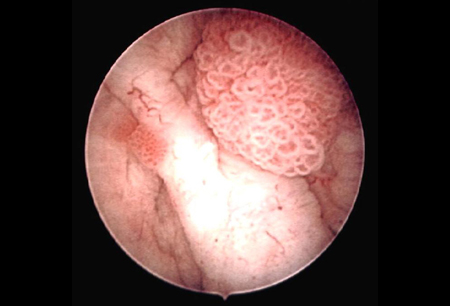

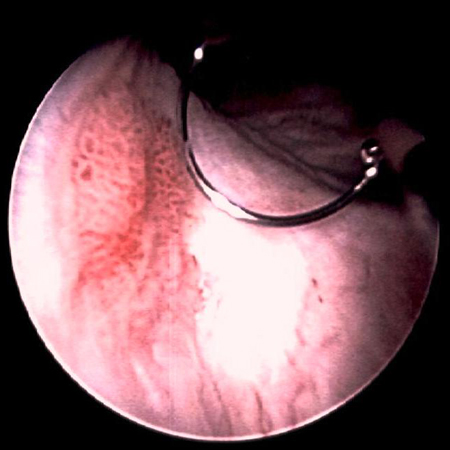

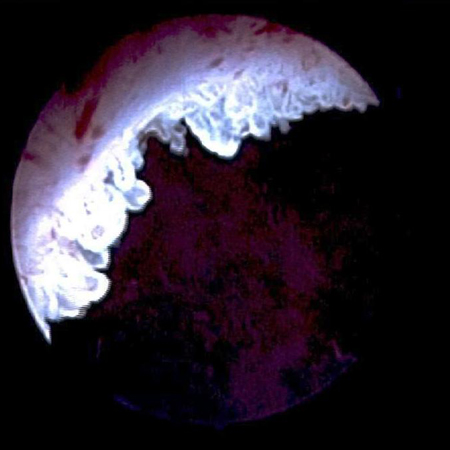

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade, non-invasive (Ta) papillary urothelial carcinoma; note adjacent satellite tumour, illustrating the field effectFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumoursFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

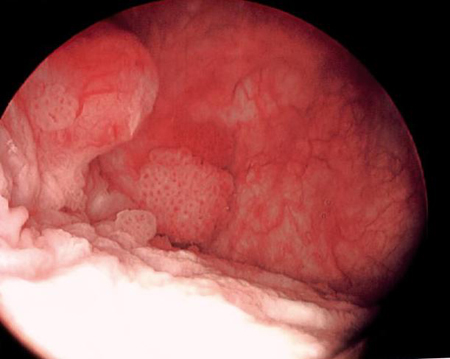

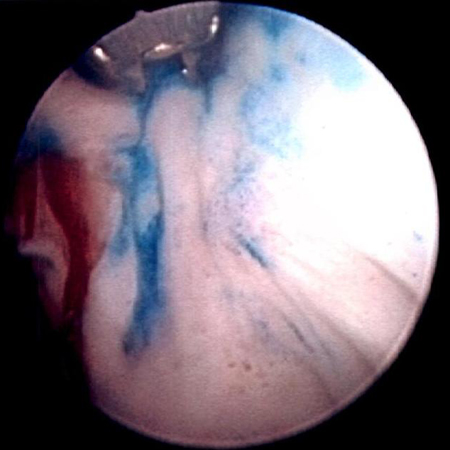

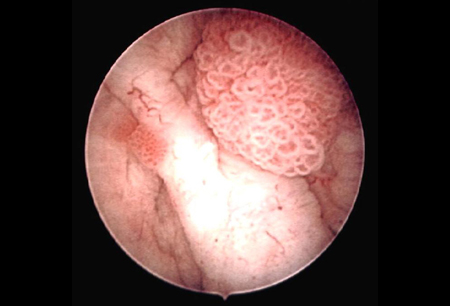

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumoursFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumours surrounded by small satellite tumours with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumour on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumours. Low- and high-grade tumours often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

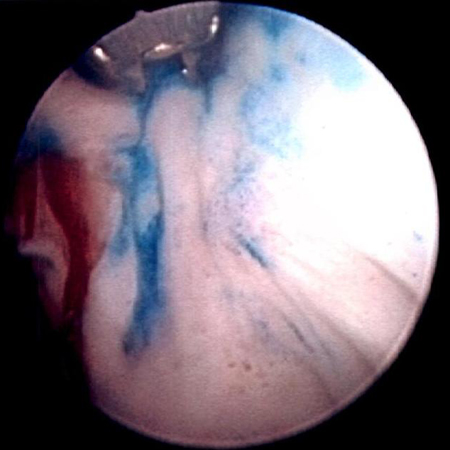

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumours surrounded by small satellite tumours with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumour on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumours. Low- and high-grade tumours often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumour at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumours not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

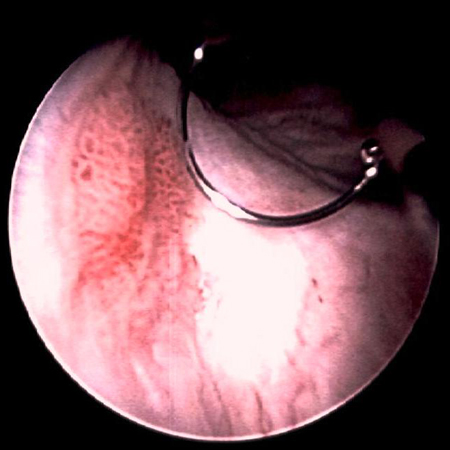

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumour at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumours not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

Transurethral resection of a bladder tumour (TURBT)

TURBT is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Initial resection allows pathological confirmation of the diagnosis with assessment of histology, grade, and depth of invasion. Fragments must be of adequate size and depth to allow for assessment of detrusor muscle invasion.

Bimanual examination under anaesthesia is performed at the time of TURBT to assess for a palpable mass or fixation to the pelvic wall, unless it is clear that the tumour is not invasive (multiple small papillary tumours).[50]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Enhanced cystoscopy (narrow-band imaging or fluorescence) may improve detection of difficult-to-visualise lesions when used to guide TURBT.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[70]Maisch P, Koziarz A, Vajgrt J, et al. Blue versus white light for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 1;12(12):CD013776.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013776.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34850382?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessmen. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Lai LY, Tafuri SM, Ginier EC, et al. Narrow band imaging versus white light cystoscopy alone for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 8;4(4):CD014887.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD014887.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35393644?tool=bestpractice.com

Blue light (fluorescence) cystoscopy is preferred to guide TURBT because it may reduce the risk of recurrence, especially for higher risk non-muscle-invasive tumours.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[70]Maisch P, Koziarz A, Vajgrt J, et al. Blue versus white light for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 1;12(12):CD013776.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013776.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34850382?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessmen. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

The evidence for reduced recurrence is less certain for narrow-band imaging cystoscopy.[60]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[71]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessmen. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Lai LY, Tafuri SM, Ginier EC, et al. Narrow band imaging versus white light cystoscopy alone for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 8;4(4):CD014887.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD014887.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35393644?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Gravestock P, Coulthard N, Veeratterapillay R, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of narrow band imaging for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2021 Dec;28(12):1212-7.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/iju.14671

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453459?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Sari Motlagh R, Mori K, Laukhtina E, et al. Impact of enhanced optical techniques at time of transurethral resection of bladder tumour, with or without single immediate intravesical chemotherapy, on recurrence rate of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. BJU Int. 2021 Sep;128(3):280-9.

https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.15383

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33683778?tool=bestpractice.com

Multiple bladder biopsies can be done at the time of initial resection to detect carcinoma in situ.

Further work-up for muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Patients with presumptive (based on TURBT and imaging) or pathologically confirmed muscle-invasive bladder cancer should have a full blood count, chemistry profile (including alkaline phosphatase), chest CT or x-ray, and abdominal/pelvic CT or MRI.[50]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[75]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

MRI is considered the best imaging modality for local staging of bladder cancer due to superior soft tissue contrast resolution compared with CT.[50]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

[75]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

Bladder multi-parametric (mp) MRI and the vesical imaging-reporting and data system (VI-RADS) has been proposed for preoperative staging and to more accurately predict muscle invasion.[76]Del Giudice F, Pecoraro M, Vargas HA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of vesical imaging-reporting and data system (VI-RADS) inter-observer reliability: an added value for muscle invasive bladder Cancer Detection. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Oct 15;12(10):2994.

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/12/10/2994

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33076505?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Del Giudice F, Barchetti G, De Berardinis E, et al. Prospective assessment of vesical imaging reporting and data system (VI-RADS) and its clinical impact on the management of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients candidate for repeated transurethral resection. Eur Urol. 2020 Jan;77(1):101-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31699526?tool=bestpractice.com

However, best practice for mpMRI and thresholds for VI-RADS scoring have yet to be determined.[78]Panebianco V, Briganti A, Boellaard TN, et al. Clinical application of bladder MRI and the Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System. Nat Rev Urol. 2024 Apr;21(4):243-251.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38036666?tool=bestpractice.com

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan may be useful in the assessment of patients at high risk of metastatic disease (e.g., those with muscle invasion and lymphovascular invasion).[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[79]Lu YY, Chen JH, Liang JA, et al. Clinical value of FDG PET or PET/CT in urinary bladder cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2012 Sep;81(9):2411-6.

http://www.ejradiology.com/article/S0720-048X(11)00657-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21899971?tool=bestpractice.com

CT, MRI, and PET/CT have similar specificities for detection of nodal metastasis, but MRI and PET/CT have superior sensitivity.[80]Crozier J, Papa N, Perera M, et al. Comparative sensitivity and specificity of imaging modalities in staging bladder cancer prior to radical cystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2019 Apr;37(4):667-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30120501?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with symptoms or clinical suspicion of bone metastasis (e.g., bone pain or elevated alkaline phosphatase) should be evaluated with MRI, fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT, or a bone scan.[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[75]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

Genetic testing

Somatic tumour testing for DNA alterations including FGFR3 may be considered to guide targeted treatment in patients with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic disease, or for access to clinical trials. Testing for HER2 overexpression and microsatellite instability/mismatch repair status may also be considered for these patients.[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Urine cytology and markers of bladder cancer

Cytology remains the standard and most accepted urinary marker for bladder cancer, but false-negatives are common.

Cytology is not routinely indicated for initial evaluation of non-visible haematuria.[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

[81]Tan WS, Sarpong R, Khetrapal P, et al. Does urinary cytology have a role in haematuria investigations? BJU Int. 2019 Jan;123(1):74-81.

https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.14459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30003675?tool=bestpractice.com

However, urine cytology has high sensitivity for high-grade tumours and CIS.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

Cytology may be useful in evaluating high-risk patients with equivocal findings on cystoscopy, or as an adjunct for patients with irritative voiding symptoms or other risk factors for carcinoma in situ (e.g., smoking, exposure to chemicals, family history).[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

[52]American Urological Association. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline (2025). 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/microhematuria

Urine cytology can also be used for post-treatment surveillance.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The sensitivity of urine cytology for low-grade tumours is limited.[21]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). 2025 [internet publication].

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Non-muscle-Invasive-BC-2025.pdf

[82]Maas M, Todenhöfer T, Black PC. Urine biomarkers in bladder cancer - current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Urol. 2023 Oct;20(10):597-614.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37225864?tool=bestpractice.com

Using the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology (TPS) improves the screening and surveillance potential of urine cytology.[83]Pastorello RG, Barkan GA, Saieg M. Experience on the use of The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytopathology: review of the published literature. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2021 Jan-Feb;10(1):79-87.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213294520303239?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33160893?tool=bestpractice.com

Urine biomarkers for bladder cancer have increased sensitivity compared with urine cytology, but specificity is lower.[61]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[84]Soorojebally Y, Neuzillet Y, Roumiguié M, et al. Urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis and NMIBC follow-up: a systematic review. World J Urol. 2023 Feb;41(2):345-59.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36592175?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Budman LI, Kassouf W, Steinberg JR. Biomarkers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008 Jun;2(3):212-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2494897

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18682775?tool=bestpractice.com

They may help to determine the most appropriate frequency for follow-up cystoscopy and aid in the diagnosis of high-risk patients, but do not replace cystoscopy and cytology.[84]Soorojebally Y, Neuzillet Y, Roumiguié M, et al. Urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis and NMIBC follow-up: a systematic review. World J Urol. 2023 Feb;41(2):345-59.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36592175?tool=bestpractice.com

Urine biomarkers include bladder tumour antigen (BTA), nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22), ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ (a fluorescence immunocytological diagnostic test using 3 tumour-related monoclonal antibodies), and UroVysion (a fluorescent in situ hybridisation [FISH] of centromeres of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 and to the 9p21 locus of chromosome 9 associated with bladder cancer).

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumoursFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumoursFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumours surrounded by small satellite tumours with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumour on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumours. Low- and high-grade tumours often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumours surrounded by small satellite tumours with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumour on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumours. Low- and high-grade tumours often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumour at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumours not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumour at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumours not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].