Aetiology

Meckel's diverticulum is a congenital abnormality of unknown cause. It results from an incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric (vitelline) duct. In the 3-week-old embryo, the yolk sac communicates with the gut through a wide vitelline duct, which receives its blood supply from paired vitelline arteries. During week 8, the duct is normally obliterated when the placenta replaces the yolk sac as the source of fetal nutrition. The left vitelline artery usually involutes and the right one forms the superior mesenteric artery.[13] Failure of obliteration of the vitelline duct may result in a spectrum of abnormalities, the most common being the formation of Meckel's diverticulum. It is a true diverticulum containing all layers of the normal intestinal wall.

Pathophysiology

Many people with Meckel's diverticulum remain asymptomatic throughout life; studies suggest the lifetime risk for symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum is 4.2% to 9.0%.[1][7][8] Symptomatic complications most often arise from ectopic tissue within the diverticulum or from residual bands that connect the apex of the diverticulum to the abdominal wall. Around 40% to 60% of Meckel's diverticula contain heterotopic mucosa, and in most cases, this is of gastric origin (most Meckel's diverticula with non-gastric heterotopic material contain pancreatic tissue).[1][3][13]

The most common causes of symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum are intestinal obstruction, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, and inflammation of the Meckel's diverticulum, with or without perforation.[1]

Bleeding occurs in 30% to 40% of symptomatic patients in both paediatric and adult patient groups.[3][14][15] Up to 90% of bleeding diverticula contain heterotopic gastric mucosa that secretes acid, resulting in ileal mucosal ulceration adjacent to the diverticulum.[13] Helicobacter pylori has not been shown to infect heterotopic gastric mucosa in Meckel's diverticulum and therefore is not believed to play a role in symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum.[16][17]

Intestinal obstruction of various causes occurs in nearly half of symptomatic children and in over one third of symptomatic adults.[1][3][15] Obstruction can result from several mechanisms:[13]

Omphalomesenteric band, the most frequent, acts as a fulcrum around which the small intestine may twist, causing a variant of mid-gut volvulus

Entrapment of intestine within a mesodiverticular band

Intussusception that is caused when the diverticulum acts as a lead point for an ileocolic or ileoileal intussusception

A diverticulum incarcerated in an abdominal wall hernia (known as Littre's hernia)

Strictures from chronic, recurrent inflammation.

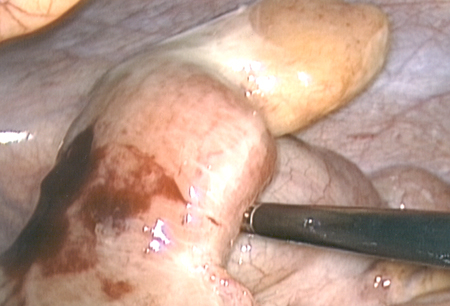

Meckel's diverticulitis is usually seen in adults rather than children, and accounts for 20% to 35% of symptomatic cases in adults.[18][19][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Inflamed Meckel's diverticulumFrom the collection of Dr Ali Tavakkoli; used with permission [Citation ends]. It is clinically indistinguishable from appendicitis, with periumbilical pain that radiates to the right lower quadrant.[3] Atypical abdominal locations of Meckel's diverticulum have been reported, owing to a mobile or 'floating' diverticulum.[5] In general, a Meckel's diverticulum is less prone to inflammation than the appendix, because most diverticula have a wide mouth and are therefore less likely to become obstructed. Diverticular obstruction can lead to distal inflammation, necrosis, and perforation, resulting in an abscess, peritonitis, or, rarely, haemoperitoneum.[6]

It is clinically indistinguishable from appendicitis, with periumbilical pain that radiates to the right lower quadrant.[3] Atypical abdominal locations of Meckel's diverticulum have been reported, owing to a mobile or 'floating' diverticulum.[5] In general, a Meckel's diverticulum is less prone to inflammation than the appendix, because most diverticula have a wide mouth and are therefore less likely to become obstructed. Diverticular obstruction can lead to distal inflammation, necrosis, and perforation, resulting in an abscess, peritonitis, or, rarely, haemoperitoneum.[6]

Meckel's diverticulum may also be a high-risk area for ileal malignancy.[20] One retrospective review of histology specimens from 373 patients found that 19 (5.1%) of the patients had evidence of malignancy; neuroendocrine tumours were the most prevalent type (63%).[21] Of the 15 patients with data on metastases, 5 (33%) had metastases at the point of diagnosis. The authors suggested that although malignancy in Meckel's diverticulum is rare, the consequences of an untreated cancer with high risk of metastases justifies prophylactic resection of incidental Meckel's diverticulum. Further studies are needed to validate this and to identify the mechanisms underlying this finding.

Classification

Clinical

No formal classification exists but commonly classified as:

Asymptomatic: incidental finding on imaging or intraoperatively

Symptomatic: may present with signs and symptoms of bleeding, obstruction, inflammation, or perforation.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer