Investigations

1st investigations to order

full blood count

comprehensive metabolic panel

CT chest/abdomen/pelvis

Test

CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, with intravenous contrast, should be performed as part of the initial diagnostic work-up.[2]

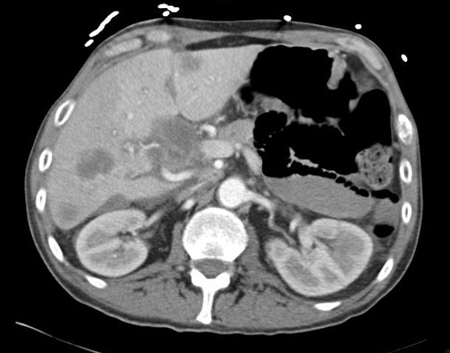

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing lesions in right hepatic lobe, with associated ascites; percutaneous biopsy of one of these lesions revealed adenocarcinoma, but no primary site was identified during routine work-up: a typical presentation of ACUPFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing liver lesions in both hepatic lobes; percutaneous biopsy of a right lobe lesion revealed adenocarcinomaFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing liver lesions in both hepatic lobes; percutaneous biopsy of a right lobe lesion revealed adenocarcinomaFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends].

Result

abnormal masses

MRI

biopsy (pathological assessment)

Test

Diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site (ACUP) requires an accurate pathological assessment of a biopsy specimen.[2]

The specimen should be obtained using core needle biopsy (preferred) and/or fine-needle aspiration from the most easily accessible metastatic site.[2] A core needle, incisional, or excisional biopsy may be performed if additional biopsy material is required.

Biopsy samples should be examined initially by light microscopy to confirm the histological subtype (i.e., adenocarcinoma).[2]

Light microscopy and standard haematoxylin and eosin staining can distinguish tumours with obvious gland formation (well-differentiated to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma) from those with scant glandular structures, consistent with adenocarcinoma due to mucin production (poorly differentiated or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma).

The degree of differentiation of the glandular structures is determined by the pathologist, and is typically classified as well-, moderately, or poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated.[29]

Result

may show well-, moderately, or poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma

immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests

Test

Once a histological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma has been confirmed, IHC testing for specific biomarkers is performed. Biopsy specimens may provide information about tumour lineage and cell (tumour) type to help identify the likely primary tumour site.[2] In some patients, IHC testing may be performed to identify potentially actionable tumour markers (e.g., RAS, HER2, or ALK rearrangements).

Testing for specific IHC markers should follow a stepwise approach based on findings from the initial diagnostic work-up and in consultation with a pathologist.[2][3]

Testing a large series of IHC markers should be avoided.[2]

The following IHC markers may be used to identify tumour lineage and likely primary site:[2]

Pan-keratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2): can indicate a carcinoma lineage.

Cytokeratin-7 (CK7): expression is generally limited to lung, breast, ovary, endometrium, and upper gastrointestinal/pancreatico-biliary cancers, and is not seen in lower gastrointestinal tract tumours.

Cytokeratin-20 (CK20): generally expressed on gastrointestinal epithelium, urothelium, and Merkel cells.

CDX2: suggests colorectal or other gastrointestinal tract primary, or pancreaticobiliary tract primary

SATB2: suggests colorectal or other gastrointestinal tract primary, or osteosarcoma primary.

TTF-1: suggestive of lung or thyroid primary.

Napsin A: suggests lung primary.

GATA3: suggests breast, urinary bladder, salivary gland primary.

PAX8: suggests renal, ovary, endometrial, cervix, thymus, or thyroid primary.

Oestrogen receptor/progesterone receptor: suggests breast, ovary, or endometrial primary.

A more extensive list of IHC markers is available in published guidelines.[2][3][23]

Information garnered from these tests must be considered in conjunction with the clinical scenario and other test results.

If initial IHC markers narrow the differential of likely primary sites, more specific antibodies can be utilised to further solidify the diagnosis.[24] Results of further testing may not alter treatment, therefore caution must be taken to avoid unnecessary delay to treatment initiation.

IHC marker profiles may occasionally differ between primary and metastatic lesions.[25][26][27]

Result

specific tumour antigens are identified via labelled antibodies

Investigations to consider

fecal occult blood test

Test

Ordered if a colorectal primary is suspected.[2]

Result

may be positive

lactate dehydrogenase

urinalysis

Test

Can be used to assess renal function, detect paraneoplastic syndromes, or evaluate for associated metabolic abnormalities.[2]

Result

normal or abnormal

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)/CT

breast imaging (mammography, MRI, ultrasound)

Test

Mammography is required for patients with a clinical presentation suggestive of breast cancer (e.g., axillary, mediastinal, and/or supraclavicular nodal involvement).[2][3][21]

Contrast-enhanced breast MRI and/or breast ultrasound is indicated if mammography is not diagnostic but there is histopathologic evidence for breast cancer.[2]

Result

may show microcalcifications (on mammography) or a mass lesion, which suggests breast cancer

transvaginal ultrasound

Test

Transvaginal ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality for women presenting with ascites to assess for the presence of an ovarian mass.

Colour Doppler should be included in the examination.[22]

Result

may show an adnexal mass, which suggests ovarian cancer

paracentesis

Test

Recommended (if technically possible) in all patients presenting with ascites to assess for peritoneal adenocarcinoma.[21]

Larger volume (>1 litre) paracentesis increases the diagnostic yield.

Result

presence of adenocarcinoma cells in the peritoneal fluid

endoscopy

Test

Endoscopy should be considered if immunohistochemistry tests suggest an upper gastrointestinal or colorectal primary, or if patients have certain clinical findings (e.g., liver metastases; positive supraclavicular nodes).[2]

Result

may show lesions for gastrointestinal or colorectal primary

direct laryngoscopy with or without oesophagoscopy and bronchoscopy

Test

Recommended for patients with cervical lymphadenopathy.[19]

The extent of examinations is dependent on the level of cervical nodes involved.

Additional immunohistochemical testing can help to confirm an occult head and neck primary tumour.

Identified lesions should be biopsied to confirm pathological concordance with the metastatic focus.

Result

may show mucosal lesions for primary head and neck carcinoma, oesophageal carcinoma, or lung carcinoma

serum tumour markers

Test

Assessment of serum tumour markers may be considered in specific clinical scenarios to identify a possible primary site.[2] However, they are non-specific and have no diagnostic role in patients with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary (ACUP).

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) should be measured to assess for possible prostate primary in the following patients: men aged >40 years with ACUP (except for those with metastases limited to the liver or brain); and all men with ACUP presenting with bone metastases or multiple sites of involvement.[2]

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) should be measured (followed by testicular ultrasound, if AFP or beta-hCG is elevated) to assess for possible testicular germ cell primary in the following patients: men aged <50 years with ACUP presenting with positive mediastinal nodes; and men aged <65 years with ACUP presenting with retroperitoneal mass.[2]

CA-125 should be measured to assess for possible ovarian primary (in consultation with a gynaecological oncologist) in the following patients with ovaries: women aged <50 years with ACUP presenting with positive mediastinal nodes; women of any age with ACUP presenting with metastases in the inguinal nodes, chest (multiple nodules), or peritoneum (with or without ascites); and women with ACUP presenting with pleural effusion or retroperitoneal mass.[2]

Testing for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 19-9, and CA 15-3 has no diagnostic role but may be useful in certain circumstances; for example, in assessing treatment response, whereby consideration may be given to establishing a baseline during diagnostic work-up.[2]

Result

may show elevated serum tumour markers (e.g., PSA, AFP, beta-hCG, CA-125)

genetic biomarker testing

Test

Can be performed to identify genetic biomarkers to guide use of biomarker-driven targeted therapy and immunotherapy.[2]

Microsatellite instability (MSI)/mismatch repair (MMR) testing can guide use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Tumour mutational burden (TMB) analysis (using validated and/or US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved assays) can guide use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Molecular profiling (e.g., using next-generation sequencing [NGS] assays) can identify actionable genetic mutations (e.g., BRAF V600E) and alterations (e.g., NTRK or RET gene fusions). Considered after histology is confirmed.

Result

may show genetic biomarkers associated with response to targeted therapy and immunotherapy (e.g., BRAF V600E mutations; NTRK gene fusions; RET gene fusions; TMB-high [≥10 mutations/megabase]; MSI-high/MMR-deficient)

Emerging tests

tissue of origin testing

Test

Tissue of origin testing (e.g., using gene expression profiling and machine learning) has been investigated in patients with cancer of unknown primary to predict a likely primary site and guide site-specific therapy.[30][31][32] Although diagnostic benefit has been demonstrated with tissue of origin testing, clinical benefit has been mixed.

Tissue of origin testing is currently not recommended in patients with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site.[2][3]

Result

may show molecular profile for a likely primary site

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer