Approach

The diagnostic work-up for adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site (ACUP) includes a complete history and physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and biopsy (pathological assessment).[2]

Unnecessary investigations (e.g., those with low diagnostic yield, and those unlikely to affect treatment decisions) should be avoided to prevent delays to treatment initiation.[16]

Key goals of the diagnostic work-up are to:

confirm the absence of a primary site,

confirm the histological subtype, and

identify patients with a favourable subtype (e.g., single metastatic lesion; clinicopathological features analogous to a known primary cancer).

Patients with a favourable subtype may undergo tailored treatment with site-specific therapy, which may improve outcomes. Approximately 20% of patients with cancer of unknown primary (CUP) have a favourable subtype.[2][3] See Aetiology (Classification) for details on favourable subtypes.

If a primary site is identified during diagnostic work-up, the patient should be managed according to guidelines pertaining to the primary site.

History and physical examination

History should include previous biopsies or malignancies, any history of removed or regressed lesions, and any family history of cancer.[2] Lifestyle history (including smoking and alcohol consumption) and a systems review can help determine the overall health and performance status of the patient.

Physical examination should include breast, genitourinary, pelvic, rectal, skin, and head and neck (including oral cavity, thyroid, and lymph nodes).[2]

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of ACUP is typically related to sites of metastatic tumour involvement, which are often multiple, and typically include the liver, lungs, lymph nodes, and bones. Rarely do presenting symptoms and signs elucidate any information regarding the primary site.

Presenting signs and symptoms include:

Pain (e.g., abdominal pain due peritoneal irritation; chest pain due to pleural irritation; bone pain due to pathological fracture with bony involvement)

Localised swelling (e.g., cervical chain adenopathy if superficial lymph nodes are involved; hepatomegaly if liver is involved)

Obstructive jaundice due to pancreaticobiliary lesions

Palpable mass

Symptoms of post-obstructive pneumonia (pneumonia occurring distal to a bronchial mass) occurring with parenchymal lung involvement (e.g., cough, wheeze, dyspnoea)

Haemoptysis occurring with parenchymal lung involvement

Constitutional symptoms (e.g., weakness, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, poor appetite, early satiety, nausea, malaise, and weight loss) that are often progressive

Neuropathic pain or weakness

Headaches and/or seizures

Ascites

Delirium

If a likely primary site is suggested by the history and physical examination, diagnostic tests should be directed to this site.

Laboratory tests

Initial laboratory tests include:[2][3]

Full blood count

Comprehensive metabolic panel (including liver function tests, creatinine, calcium, electrolytes).

Additional tests that may be performed if clinically indicated include:[2][3][17]

Fecal occult blood test (if colorectal primary is suspected)

Lactate dehydrogenase (to assess disease activity and tumour burden; can inform risk assessment and prognosis)

Urinalysis (to assess renal function, detect paraneoplastic syndromes, or evaluate for associated metabolic abnormalities)

Imaging studies

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, with intravenous contrast, should be performed as part of the initial diagnostic work-up.[2]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without intravenous contrast can be performed if CT scan is contraindicated, or if patients have suspected head and neck cancers, brain metastases, or pelvic neoplasms.[3][18][19][20]

Other imaging studies

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/CT (FDG-PET/CT) is not routinely recommended, but may be considered if contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is contraindicated, or if clinically indicated (e.g., if a patient presents with a neck mass).[2][19]

Mammography is required for patients with a clinical presentation suggestive of breast cancer (e.g., axillary, mediastinal, and/or supraclavicular nodal involvement).[2][3][21] Contrast-enhanced breast MRI and/or breast ultrasound is indicated if mammography is not diagnostic but there is histopathologic evidence for breast cancer.[2]

Transvaginal ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality for women presenting with ascites to assess for the presence of an ovarian mass. Colour Doppler should be included in the examination.[22]

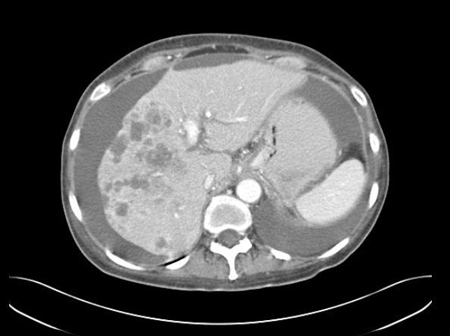

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing lesions in right hepatic lobe, with associated ascites; percutaneous biopsy of one of these lesions revealed adenocarcinoma, but no primary site was identified during routine work-up: a typical presentation of ACUPFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing liver lesions in both hepatic lobes; percutaneous biopsy of a right lobe lesion revealed adenocarcinomaFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, revealing numerous enhancing liver lesions in both hepatic lobes; percutaneous biopsy of a right lobe lesion revealed adenocarcinomaFrom the personal collection of Dr D. Cosgrove [Citation ends].

Biopsy and pathological assessment

Diagnosis of ACUP requires an accurate pathological assessment of a biopsy specimen.[2] The specimen should be obtained using core needle biopsy (preferred) and/or fine-needle aspiration from the most easily accessible metastatic site.[2] A core needle, incisional, or excisional biopsy may be performed if additional biopsy material is required.

Consult with the pathologist prior to any biopsy to determine the extent of specimen required to differentiate between likely primary sites.

Biopsy samples should be examined initially by light microscopy to confirm the histologic subtype (i.e., adenocarcinoma).[2]

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests

Once a histological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma has been confirmed, IHC testing for specific biomarkers is performed. Biopsy specimens may provide information about tumour lineage and cell (tumour) type to help identify the likely primary tumour site.[2] In some patients, IHC testing may be performed to identify potentially actionable tumour markers (e.g., RAS, HER2, or ALK rearrangements).

Testing for specific IHC markers should follow a stepwise approach based on findings from the initial diagnostic work-up and in consultation with a pathologist.[2][3] Testing a large series of IHC markers should be avoided.[2]

The following IHC markers may be used to identify tumour lineage and likely primary site:[2]

Pan-keratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2): can indicate a carcinoma lineage

Cytokeratin-7 (CK7): expression is generally limited to lung, breast, ovary, endometrium, and upper gastrointestinal/pancreatico-biliary cancers, and is not seen in lower gastrointestinal tract tumours

Cytokeratin-20 (CK20): generally expressed on gastrointestinal epithelium, urothelium, and Merkel cells

CDX2: suggests colorectal or other gastrointestinal primary, or pancreaticobiliary tract primary

SATB2: suggests colorectal or other gastrointestinal tract, or osteosarcoma primary

TTF-1: suggess lung or thyroid primary

Napsin A: suggests lung primary

GATA3: suggests breast, urinary bladder, or salivary gland primary

PAX8: suggests renal, ovary, endometrial, cervix, thymus, or thyroid primary

Oestrogen receptor/progesterone receptor: suggests breast, ovary, or endometrial primary

A more extensive list of IHC markers is available in published guidelines.[2][3][23]

Information garnered from these tests must be considered in conjunction with the clinical scenario and other test results.

If initial IHC markers narrow the differential of likely primary sites, more specific antibodies can be utilised to further solidify the diagnosis.[24] Results of further testing may not alter treatment; therefore, caution must be taken to avoid unnecessary delay to treatment initiation.

IHC marker profiles may occasionally differ between primary and metastatic lesions.[25][26][27]

Further investigations

Some patients may undergo additional tests depending on clinical presentation, findings from initial investigations, and pathological assessment.

Endoscopic studies

Endoscopy should be considered if IHC tests suggest upper gastrointestinal or colorectal primary, or if patients have certain clinical findings (e.g., liver metastases; positive supraclavicular nodes).[2]

Direct laryngoscopy with or without esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy is recommended for patients with cervical lymphadenopathy.[19] The extent of examination is dependent on the level of cervical nodes involved. Additional IHC testing can help to confirm an occult head and neck primary tumour.

Paracentesis

Paracentesis (if technically possible) is recommended in all patients presenting with ascites to assess for peritoneal adenocarcinoma.[21]

Serum tumour markers

Assessment of serum tumour markers may be considered in specific clinical scenarios to identify a possible primary site.[2] However, they are nonspecific and have no diagnostic role in patients with ACUP.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) should be measured to assess for possible prostate primary in the following patients:[2]

Men aged >40 years with ACUP (except for those with metastases limited to the liver or brain)

All men with ACUP presenting with bone metastases or multiple sites of involvement

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) should be measured (followed by testicular ultrasound, if AFP or beta-hCG is elevated) to assess for possible testicular germ cell primary in the following patients:[2]

Men aged <50 years with ACUP presenting with positive mediastinal nodes

Men aged <65 years with ACUP presenting with retroperitoneal mass

CA-125 should be measured to assess for possible ovarian primary (in consultation with a gynecologic oncologist) in the following patients with ovaries:[2]

Women aged <50 years with ACUP presenting with positive mediastinal nodes

Women of any age with ACUP presenting with metastases in the inguinal nodes, chest (multiple nodules), or peritoneum (with or without ascites)

Women with ACUP presenting with pleural effusion or retroperitoneal mass

Testing for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 19-9, and CA 15-3 has no diagnostic role but may be useful in certain circumstances; for example, in assessing treatment response, whereby consideration may be given to establishing a baseline during diagnostic work-up.[2]

Genetic biomarker testing

The following investigations can be performed to identify genetic biomarkers to guide use of biomarker-driven targeted therapy and immunotherapy:[2]

Microsatellite instability (MSI)/mismatch repair (MMR) testing to guide use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Tumour mutational burden (TMB) analysis (using validated and/or US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved assays) to guide use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Molecular profiling (e.g., using next-generation sequencing [NGS] assays) to identify actionable genetic mutations (e.g., BRAF V600E) and alterations (e.g., NTRK or RET gene fusions). Considered after histology is confirmed.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer