Aetiology

The primitive midgut becomes identifiable in the 4th week of gestation.[8] In the 5-week embryo, the midgut is a linear tube from duodenum to rectum suspended from the dorsal abdominal wall by a continuous mesentery.[9] At this stage, the duodenum begins extending in a straight anterior direction into the cephalic limb (jejunum and ileum) to the vitelline duct, which communicates with the extra-corporeal yolk sac. The duct exits at the terminal point of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). This cephalic, or duodeno-jejunal, limb runs parallel and superior to the SMA. The caudal, or caeco-colic, limb courses posteriorly, running parallel and inferior to the SMA to the cloaca.

At 6 weeks, the midgut herniates out of the abdomen into the umbilical cord until the 10th week, when it returns. There is a 90° anti-clockwise rotation during herniation and an additional 180° rotation during return to a complete 270° anti-clockwise rotation.[9]

During the return, while the caecum is completing a separate 270° anti-clockwise rotation anterior to the small intestine, the colonic attachments to the posterior abdominal wall develop.

Rotation may be arrested at any point in this process, creating subsequent abnormalities in intestinal fixation points, and the myriad conditions described by the term malrotation.

Pathophysiology

In the scenario of little or no rotation, the duodenum does not completely rotate and crosses posterior to the SMA to allow creation of a normal ligament of Treitz on the left side of the abdomen. The duodenum continues out into the proximal jejunum on the right side of the SMA continuing to the terminus of the SMA within the ileum. The remainder of the bowel courses back so that the colon is on the left side of the SMA. If lateral attachments (Ladd’s bands) between the caecum and the right upper abdominal wall are created in direct proximity to the duodenum, as in the circumstance of classic incomplete rotation, the caecum will lie anterior to the duodenum and the proximal and distal portions of the small bowel mesentery are folded, allowing the caecum to be located back to the right side of the SMA.

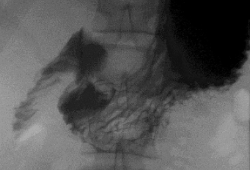

If there is less rotation initially, as in non-rotation, the duodenum then lies at the base of the mesentery on the right, and the colon at the base on the left of the SMA, with a variable distance between these two points. The relative narrowness between these two fixation points in either rotational anomaly is what creates the risk of midgut volvulus. A shorter distance between these fixation points allows the narrow pedicle of the small bowel to easily twist around into a volvulus. An abrupt obstruction of the duodenum results, creating the bilious vomiting seen with volvulus. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Malrotation with volvulus causing complete obstruction of the duodenum that does not sweep to the left, as seen on upper GI contrastFrom the collection of Dr S.D. St Peter [Citation ends].

If the twisting at the base also obstructs flow in the SMA, the entire small intestine and a portion of the colon become acutely ischaemic, and necrosis may soon follow. As such, midgut volvulus causes significant morbidity and mortality unless emergency surgical intervention is performed to prevent irreversible loss of most of the intestine.[2]

In addition to volvulus, Ladd’s bands may contribute to more subtle and likely chronic symptoms from a partial duodenal obstruction. Without concomitant volvulus, these symptoms rarely cause significant morbidity.

Classification

Clinical classification schema

Normal rotation

Two separate, but connected, 270° anti-clockwise turns occur in the foregut-midgut junction and midgut-hindgut junction resulting in a retro-peritoneal duodenum, ligament of Treitz on the left of the spine, and caecum fixed to the right lower lateral abdominal wall. Hence, a broad-based mesentery is created and fixed at opposing sites in the left upper and right lower abdomen.

Occurrence of midgut volvulus does not occur in this setting without secondary adhesions present anteriorly.

Incomplete rotation (or classic malrotation) is limited (90° to 180°) counterclockwise rotation in the foregut-midgut and midgut-hindgut junctions resulting in:

Failure of the duodeno-jejunal limb to rotate posterior and to the left of the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in the lack of a ligament of Treitz, or one that lies to the right of the spine

Incomplete rotation of the caeco-colic limb, which normally leads to Ladd’s bands attaching the caecum across the duodenum in the right upper abdomen

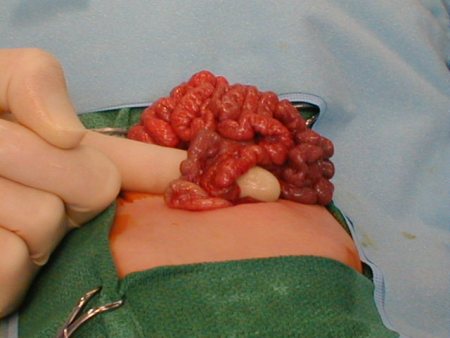

Close proximity of the fixation points for the proximal and distal midgut mesentery.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Narrow base of mesentery in malrotationFrom the collection of Dr S. Shew [Citation ends].

Non-rotation

Minimal (<90°) rotations occurring in the primitive gut junctions around the superior mesenteric artery resulting in no ligament of Treitz, lack of lateral caecal fixation, and variable proximity between the proximal and distal midgut mesentery.

Reverse rotation

Partial clockwise rotation of the foregut-midgut junction anterior to the superior mesenteric artery; this is rare.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer