Approach

Complete history and physical examinations are both important for the diagnosis of a popliteal cyst. A duplex ultrasound of the limb confirms the clinical diagnosis.[19]

Clinical evaluation

Location, duration, and type of pain should be determined to evaluate whether symptoms can be attributed to the cyst itself, or are secondary to the underlying cause of the cyst. Previous history of knee trauma, arthritis, or history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) should be sought. The popliteal fossa should be evaluated for masses. The leg should be evaluated for swelling secondary to oedema, and a vascular examination performed.

A ruptured popliteal cyst may be associated with calf ecchymosis and significant pain, and, rarely, with compartment syndrome, presenting with sensory or motor deficits secondary to elevated intra-compartmental pressures. In some patients, there may be decreased range of movement and inability to straighten the knee.

Popliteal cysts are usually visible as a bulge behind the knee, which is particularly noticeable upon standing and in comparison to the uninvolved knee. Cysts are generally soft and minimally tender. It is common for a popliteal cyst to expand and shrink over time. Large cysts, especially if ruptured, will produce calf tenderness on examination.

Tests

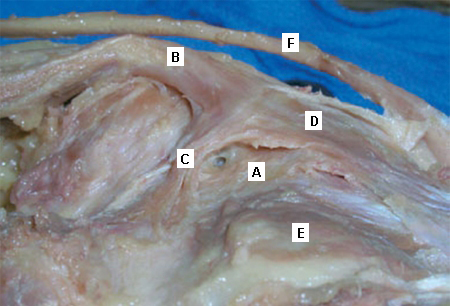

Patients suspected of having a popliteal cyst on clinical examination should undergo a duplex ultrasound of the limb.[19] This helps to identify the cyst and evaluates other possible pathologies such as DVT, haematoma, popliteal artery aneurysm, popliteal vein aneurysm, or soft tissue mass. However, while ultrasound has high specificity and sensitivity for detecting popliteal cysts, it is user dependent; diagnosis is therefore influenced by the skill of the operator.[20][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anatomical dissection of the posteromedial knee capsule. The weak area (A) is identified between the two expansions of the semimembranosus muscle (B), the oblique popliteal ligament (C), and the expansion over the sheath of the popliteus muscle (D). The semitendinosus muscle (E) and popliteus muscle (F) are also indicatedAdapted from Labropoulos N, Shifrin DA, Paxinos O. New insights into the development of popliteal cysts. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1313-1318; used with permission [Citation ends].

If a popliteal cyst is identified, the next step is to identify the underlying aetiology of cyst formation. The presence of a popliteal cyst may be the first sign of underlying joint pathology. The most common joint pathologies include meniscal tear and knee joint arthritis. Appropriate further work-up is then directed by the cause. See Meniscal tear; Osteoarthritis.

If ultrasound fails to show a cause for the patient's symptoms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful to identify any underlying knee joint pathology.[19] Computed tomography scan is an alternative, but MRI is the preferred test, with a greater yield.

Knee x-rays are not diagnostic for popliteal cysts but should be obtained as they can identify loose bodies (small fragments of bone and cartilage in the synovial fluid) and other commonly associated conditions such as osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis.[21] The presence of calcification should raise the suspicion of malignancy.[22]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer