Investigations

1st investigations to order

FBC

Test

Always required.

May demonstrate anaemia or iron deficiency.

Result

low Hb, microcytosis, hypochromia

blood type and crossmatch

Test

Recommended if transfusion may be required.

Result

blood type

urea and electrolyte

Test

May demonstrate renal impairment or failure.

May indicate high urea secondary to upper gastrointestinal bleeding and/or dehydration.

Result

high urea/Cr; high urea

coagulation status

Test

Assessment of coagulation status should be performed by measuring the INR, PT, and PTT in all patients. For patients taking anticoagulants and having haemodynamical instability, vitamin K supplementation, prothrombin complex concentrate, fresh frozen plasma, or direct oral anticoagulant reversal agents may be appropriate.

Result

prolongation of PT or PTT or INR could be present suggesting a decreased clotting ability

oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

Test

Most common method of ruling out an upper gastrointestinal bleed.

Non-diagnostic in 10% of patients.[47]

If bleeding is too severe or lesion is not identified, proceeding to CT angiography is recommended.

Result

gastric and proximal duodenum epithelium abnormalities and findings that could be the source of bleeding including ulcers, polyps, masses, angiodysplasias or vessels

push enteroscopy

Test

As an alternative to oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD), push enteroscopy may be performed using a paediatric colonoscope to intubate deeper into the small bowel/proximal jejunum, compared with standard OGD.

If the bleeding lesion is located to the proximal small bowel (and is not a mass), push enteroscopy may then be used to identify and cauterise the lesion.[8] Push enteroscopy involves passing ('pushing') a long, fine endoscope (typically 2.6 m long, with a diameter of 11.2 mm) through the stomach, duodenum, and onwards into the jejunum.

Result

small bowel pathology that could be the source of bleeding including ulcers, polyps, masses, angiodysplasias

colonoscopy

Test

Most common method of establishing the diagnosis of colonic angiodysplasias.

Non-diagnostic in 10% of patients.[47]

Emergency colonoscopy may miss diagnosis in 40% of patients.[48][49] In hospitalised patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding, the American College of Gastroenterology and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend a non-urgent inpatient colonoscopy, as re-bleeding may be missed if an urgent colonoscopy performed.[35][38]

If bleeding is too severe or lesion is not identified, proceeding to CT angiography is recommended.

Result

colonic and terminal ileum abnormalities that could be the source of bleeding including ulcers, polyps, masses, angiodysplasias or vessels

Investigations to consider

wireless capsule enteroscopy

Test

Capsule endoscopy should be the next test in the evaluation of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding when findings on standard examinations (OGD, colonoscopy, and/or mesenteric angiography) are negative.[8][39][40][50]

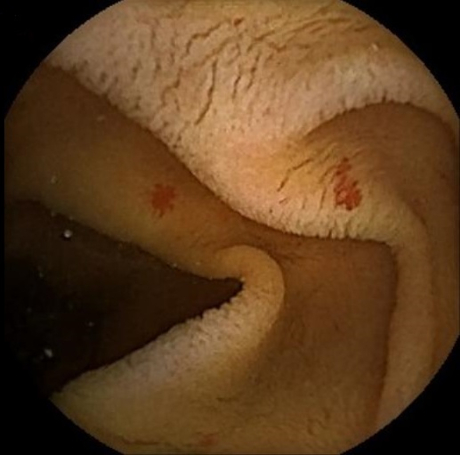

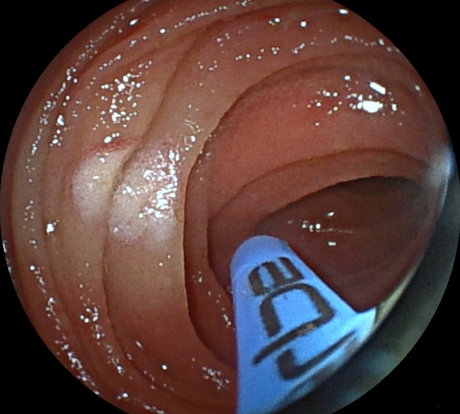

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel angiodysplasia seen during small bowel capsule endoscopyFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

Capsule endoscopy allows wireless evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract.[9] It is typically performed in elective settings. One retrospective cohort study reported 66.3% favourable outcome in patients after capsule endoscopy-guided therapy.[51]

Can detect selective caecal lesions.

Result

abnormal small bowel epithelium: ulcers, angiodysplasias, erosions, small bowel mass, stenosis

CT angiography

Test

CT angiography should be performed as the first diagnostic study in emergency setting in patients with haemodynamic instability and can be considered as the initial diagnostic study in such patients when active bleeding is suspected.[18] Recommendations are against using CT angiography as a first-line test in haemodynamically stable patients in whom bleeding has subsided as the yield is low.[18] CT angiography is reported to improve the detection of gastrointestinal bleeding compared with colonoscopy and standard angiography.[42][43][44] In patients with overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding, CT imaging can determine the location, assess the intensity of the bleed, and identify the cause of bleeding.[18]

CT angiography is rapid and non-invasive, but lacks therapeutic capability. Radiation exposure and contrast allergy are potential concerns. In this setting, a capsule endoscopy may be more appropriate.

Result

active gastrointestinal bleeding from an angiodysplastic vessel when intravenous contrast is seen in bowel lumen

selective mesenteric angiography

Test

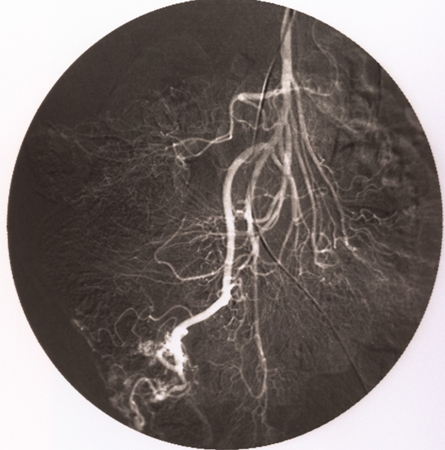

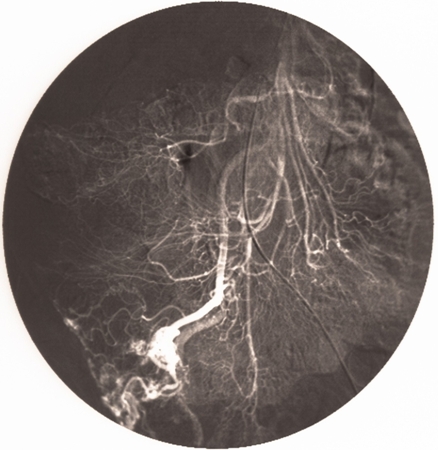

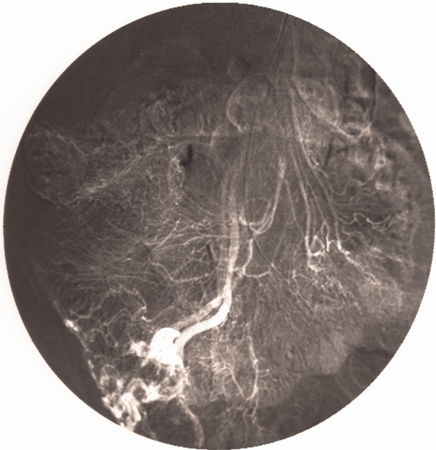

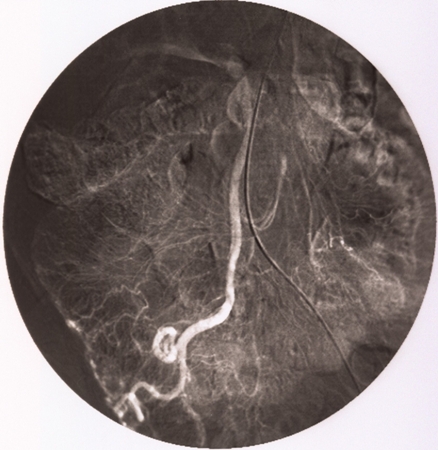

Indicated in massive haemorrhage, when endoscopy is non-diagnostic, or to control bleeding when therapeutic endoscopy fails.[52][53][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogram. Vascular tufts and tangles from local mass of irregular vessels displayedImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogramImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ileocolic artery on mesenteric angiogramImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Early and intensely filling vein resulting from direct arteriovenous communicationImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

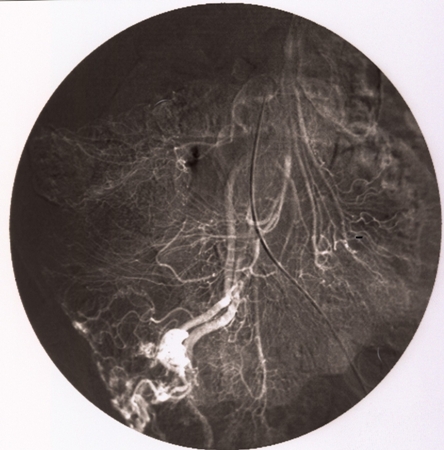

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Early and intensely filling vein resulting from direct arteriovenous communicationImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mesenteric angiogram. Persistent opacification beyond normal venous phaseImage donated by Dr DeNunzio, Derby, UK [Citation ends].

Accuracy in detecting lower gastrointestinal bleeding ranges from 40% to 92%.[54][55][56][57]

Has potential to control bleeding (by vasopressin or embolisation techniques) and to localise bleeding to facilitate bowel resection.

Result

active gastrointestinal bleeding, with contrast in bowel lumen; vascular tufts or tangles from local mass of irregular vessels; early and intensely filling vein resulting from direct arteriovenous communication and persistent opacification beyond normal venous phase

technetium Tc-99m radionuclide scan

Test

Positive result when focus of activity is identified, and increases in intensity with time.

Indicated to detect and localise mild to moderate bleeding.

Can detect bleeding rates as slow as 0.05 to 0.1 mL/minute.[58]

Labelled erythrocytes have long intravascular half-life that enables continuous imaging of the gastrointestinal tract for several hours and, thus, are preferred for lower gastrointestinal bleeding imaging over Tc-99m sulfur colloid.[18] Tc-99m-labelled erythrocytes remain in the bloodstream for 24 hours; patients can be re-scanned without re-injection 24 hours later if initial scan is negative.[59][60]

Sensitivity is 93% and specificity is 95%.[61]

Although sensitive at detecting bleeding, poor at localising bleeding site.[18]

Can be used only in haemodynamically stable patients as labelling takes a long time.[18]

Result

positive

CT enterography

Test

In patients with suspected small bowel bleeding and negative capsule endoscopy, multi-phase CT enterography should be performed to locate the bleeding source, especially in those aged >40 years.[8][18] In patients with haemodynamic stability with suspected small bowel bleeding, CT enterography should be performed instead of CT angiography if colonoscopy, OGD, and capsule endoscopy are negative.[18] CT enterography can be considered when capsule endoscopy fails to identify the bleeding source and ongoing bleeding is suspected.[8][18] CT enterography is also the preferred technique for haemodynamically stable patients with suspected small bowel bleeding who are at risk for video capsule retention.[18]

Result

luminal contrast extravasation on arterial phase or portal venous phase

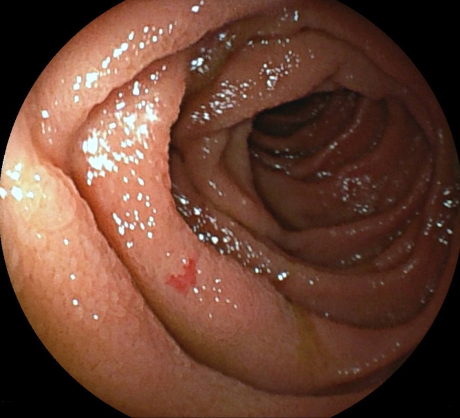

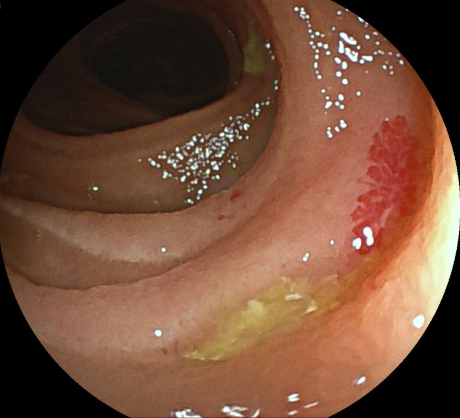

device-assisted enteroscopy

Test

Device-assisted enteroscopy (DAE), such as single-balloon or double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), may be performed. DAE involves a fine, long endoscope (200 cm) with a balloon on its tip, and in case of DBE with an overtube with a second balloon. Through the inflation and deflation of balloons, along with alternating pushing and pulling manoeuvres, DAE allows for deep progression into the small bowel either via the oral or anal route.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasiaFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasia after treatment with argon plasma coagulationFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic (device-assisted enteroscopy) image of small bowel angiodysplasia after treatment with argon plasma coagulationFrom the personal collection of Dr Elli, Milan, Italy; used with permission [Citation ends].

Result

small bowel abnormalities and findings that could be the source of bleeding including ulcers, polyps, masses, angiodysplasias

Emerging tests

magnetic resonance angiography

Test

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be considered if conventional investigation does not show bleeding sources. Further investigation is required. May be considered in patients in whom CT angiography is unsuitable because of persistence of oral contrast in the bowel or in younger patients to avoid radiation exposure.[8][34]

MRA lacks therapeutic capability and may require use of intravenous contrast agent.[4]

Result

active gastrointestinal bleeding shown as presence of contrast in bowel lumen

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer