History, together with a physical and neurological examination, are typically suggestive of an intracranial mass lesion. In the setting of trauma, intracranial haematomas are typically high on the list of differential diagnoses.[47]Vos PE, Alekseenko Y, Battistin L, et al; European Federation of Neurological Societies. Mild traumatic brain injury: EFNS guidelines on mild traumatic brain injury. Eur J Neurol. 2012 Feb;19(2):191-8.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03581.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22260187?tool=bestpractice.com

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scans are imperative when assessing a patient with a moderate or high risk for intracranial injury.[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

Acute subdural haematoma (SDH) typically presents with acute neurological decline following a traumatic brain injury (TBI), which may have caused a temporary or ongoing loss of consciousness. Symptoms may develop over minutes or hours and include: change in consciousness level/coma; acutely altered mental state (e.g., confusion, irritation, changed behaviour); haemiparesis; dizziness; seizures; progressive headache; nausea and vomiting.

Chronic SDH typically presents with symptoms that mimic a gradually evolving mass lesion (e.g., intracranial neoplasm), including focal limb weakness, worsening cognition, dysphasia, headache, and gait disturbance.[30]Rickard F, Gale J, Williams A, et al. New horizons in subdural haematoma. Age Ageing. 2023 Dec 1;52(12):afad240.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38167695?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Dixon-Woods M, et al. Protocol for the development of a multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline for the care of patients with chronic subdural haematoma. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;8:390.

https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/8-390/v1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38434734?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Wat R, Mammi M, Paredes J, et al. The effectiveness of antiepileptic medications as prophylaxis of early seizure in patients with traumatic brain injury compared with placebo or no treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019 Feb;122:433-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30465951?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Blaauw J, Meelis GA, Jacobs B, et al. Presenting symptoms and functional outcome of chronic subdural hematoma patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022 Jan;145(1):38-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34448196?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Brennan PM, Kolias AG, Joannides AJ, et al. The management and outcome for patients with chronic subdural hematoma: a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study in the United Kingdom. J Neurosurg. 2017 Oct;127(4):732-9.

https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/127/4/article-p732.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27834599?tool=bestpractice.com

The symptoms depend on the size and location of the SDH and usually worsen progressively over days or weeks.[32]Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Dixon-Woods M, et al. Protocol for the development of a multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline for the care of patients with chronic subdural haematoma. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;8:390.

https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/8-390/v1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38434734?tool=bestpractice.com

Rare presenting features that suggest progression of the chronic SDH include drowsiness/ decreased consciousness and seizures.[33]Teale EA, Iliffe S, Young JB. Subdural haematoma in the elderly. BMJ. 2014 Mar 11;348:g1682.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24620354?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Blaauw J, Meelis GA, Jacobs B, et al. Presenting symptoms and functional outcome of chronic subdural hematoma patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022 Jan;145(1):38-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34448196?tool=bestpractice.com

According to one retrospective analysis of 1307 patients with chronic SDH, seizures were present in 2%.[51]Blaauw J, Meelis GA, Jacobs B, et al. Presenting symptoms and functional outcome of chronic subdural hematoma patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022 Jan;145(1):38-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34448196?tool=bestpractice.com

The same study found the mean Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at presentation to be 14.2; this reflects the typical finding that the GCS score tends not to be markedly reduced in chronic SDH.[51]Blaauw J, Meelis GA, Jacobs B, et al. Presenting symptoms and functional outcome of chronic subdural hematoma patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2022 Jan;145(1):38-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34448196?tool=bestpractice.com

Because of brain atrophy over time, older patients with chronic SDH are often less symptomatic than younger patients, who are more susceptible to the mass effect from an intracranial haematoma.[53]Rudy RF, Catapano JS, Jadhav AP, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization to treat chronic subdural hematoma. Stroke Vasc Interv Neurol. 2023;3:e000490.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/SVIN.122.000490#:~:text=Embolization%20has%20the%20advantages%20of,population%20associated%20with%20significant%20comorbidities.

Presentation may be delayed in an older person as age-related cerebral atrophy partially protects against mass effect.[30]Rickard F, Gale J, Williams A, et al. New horizons in subdural haematoma. Age Ageing. 2023 Dec 1;52(12):afad240.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38167695?tool=bestpractice.com

If a patient presents with a suspected acute or chronic SDH, it is important to assess their level of consciousness on the GCS, taking account of any baseline impairment due to a pre-existing neurological condition (e.g., dementia).[54]Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4136544?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Key features in the history include recent history of trauma, loss of consciousness or period of decreased alertness, potential seizure activity, loss of bowel and bladder continence, headache, weakness or sensory changes, or changes in cognition, speech, or vision.[3]Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Apr;24(2):294-307.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399248?tool=bestpractice.com

Enquiry about recent use of antiplatelet agents, antithrombotic agents, or anticoagulants is imperative.[12]Stubbs DJ, Davies B, Hutchinson P, et al. Challenges and opportunities in the care of chronic subdural haematoma: perspectives from a multi-disciplinary working group on the need for change. Br J Neurosurg. 2022 Oct;36(5):600-8.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02688697.2021.2024508

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35089847?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients should be asked about any history of easy bruising or difficulty stopping bleeding from small cuts or scrapes. A history of liver or renal disease is important when evaluating coagulation and platelet function.

If a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of chronic SDH, any history of head trauma, however minor, should be ascertained, as should any recent falls, with or without head injury. Chronic SDH usually develops following a trivial, often forgotten, head trauma but it may also develop after a fall without a direct head injury, or spontaneously without any preceding trauma.[30]Rickard F, Gale J, Williams A, et al. New horizons in subdural haematoma. Age Ageing. 2023 Dec 1;52(12):afad240.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38167695?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Miah IP, Holl DC, Blaauw J, et al. Dexamethasone versus surgery for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 15;388(24):2230-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37314705?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Dixon-Woods M, et al. Protocol for the development of a multidisciplinary clinical practice guideline for the care of patients with chronic subdural haematoma. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;8:390.

https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/8-390/v1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38434734?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Teale EA, Iliffe S, Young JB. Subdural haematoma in the elderly. BMJ. 2014 Mar 11;348:g1682.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24620354?tool=bestpractice.com

Only about half of those presenting with chronic SDH give a history of a direct head trauma or a fall with a head injury.[33]Teale EA, Iliffe S, Young JB. Subdural haematoma in the elderly. BMJ. 2014 Mar 11;348:g1682.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24620354?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients should be asked about alcohol intake since people with a history of chronic harmful alcohol use are at higher risk of SDH and excessive alcohol intake is associated with cerebral atrophy. In addition, affected individuals are more likely to develop a coagulopathy and are more prone to falls and the resultant risk of trauma-related SDH compared with people who do not drink harmful levels of alcohol.[38]Doherty DL. Posttraumatic cerebral atrophy as a risk factor for delayed acute subdural hemorrhage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988 Jul;69(7):542-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3389997?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Sim YW, Min KS, Lee MS, et al. Recent changes in risk factors of chronic subdural hematoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012 Sep;52(3):234-9.

https://www.jkns.or.kr/journal/view.php

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23115667?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Whaley CC, Young MM, Gaynor BG. Very high blood alcohol concentration and fatal hemorrhage in acute subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg. 2019 Oct;130:454-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31252079?tool=bestpractice.com

Lastly, clinicians should have a higher index of suspicion for SDH in patients who have recently had a lumbar puncture or drain, a transsphenoidal procedure, or have an intracranial shunt.[41]Hannan CJ, Almhanedi H, Al-Mahfoudh R, et al. Predicting post-operative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak following endoscopic transnasal pituitary and anterior skull base surgery: a multivariate analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2020 Jun;162(6):1309-15.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32318930?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Beck J, Gralla J, Fung C, et al. Spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak as the cause of chronic subdural hematomas in nongeriatric patients. J Neurosurg. 2014 Dec;121(6):1380-7.

https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/121/6/article-p1380.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25036203?tool=bestpractice.com

SDHs can occur in patients with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, often due to ‘over-shunting’ - removal of too much cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which creates a physiological pulling force into the subdural space.[43]Berger A, Constantini S, Ram Z, et al. Acute subdural hematomas in shunted normal-pressure hydrocephalus patients - management options and literature review: a case-based series. Surg Neurol Int. 2018 Nov 28;9:238.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6287333

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30595959?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Sundström N, Lagebrant M, Eklund A, et al. Subdural hematomas in 1846 patients with shunted idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: treatment and long-term survival. J Neurosurg. 2018 Sep;129(3):797-804.

https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/129/3/article-p797.xml?tab_body=fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29076787?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Physical signs of trauma should be sought on the head and neck. Scalp and face abrasions, lacerations, avulsions, or ecchymosis are important to note. Periorbital or retroauricular ecchymosis, and/or otorrhoea or rhinorrhoea, may indicate occult basilar skull fracture. It is also important to always evaluate the cervical spine for tenderness, deformity, ecchymosis, or step-off in all patients with suspected head injury. Cervical spine immobilisation should always be maintained as a protective measure, until potential injury is excluded.

Neurological examination

Calculation of the admission GCS score, in the absence of sedation and paralysis, is important for prognosis and management.[54]Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4136544?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, pupil size, symmetry, and reactivity should be noted.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

If the patient is able to follow commands, the presence of a pronator drift (indicating early hemiparesis) should be noted. If the patient cannot follow commands, the response to stimulation in all four extremities is noted. In older adults, the verbal component of the GCS may be confounded by pre-existing conditions such as delirium, dementia, and aphasia.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

The total GCS score is the sum of points from eye opening, verbal response, and motor response scores (from 3 to 15 points total):

Eye opening: spontaneous (4 points), to verbal command (3 points), to painful stimulation (2 points), none (1 point)

Motor response: obeys verbal commands (6 points), localises to painful stimulus (5 points), flexion withdrawal to painful stimulus (4 points), abnormal flexion response to painful stimulus (3 points), extensor response to painful stimulus (2 points), none (1 point)

Verbal response: oriented conversation (5 points), disorientated conversation (4 points), inappropriate words (3 points), incomprehensible sounds (2 points), none (1 point).

[

Glasgow Coma Scale

Opens in new window

]

The patient may have signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) as the haematoma size increases. These might include altered mental status, oculomotor and pupillary deficits, and vomiting. Late signs of raised ICP include bilateral fixed and dilated pupils and Cushing’s triad (widened pulse pressure due to systolic hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respiration).

Pupillary abnormalities are observed on presentation in 30% to 50% of patients with acute SDH.[55]Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al; Surgical Management of Traumatic Brain Injury Author Group. Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006 Mar;58(suppl 3):S16-24;discussion Si-iv.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16710968?tool=bestpractice.com

The pupillary light response provides diagnostic and prognostic information in patients with TBI.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

Some degree of pupillary asymmetry may be normal, but the development of new pupillary asymmetry can indicate compression of the brainstem with impending uncal herniation, triggering the need for further evaluation and intervention.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

A unilateral unreactive pupil is consistent with an ipsilateral mass lesion, while bilaterally fixed and dilated pupils indicate transtentorial herniation and portend a poor overall prognosis for functional recovery.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

CT of the brain

Non-contrast cranial CT imaging is the investigation of choice for all patients who have suspected acute or chronic SDH based on the history and the physical and neurological examinations.[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Catana D, Koziarz A, Cenic A, et al. Subdural hematoma mimickers: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2016 Sep;93:73-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27268313?tool=bestpractice.com

CT is critical in the evaluation of all head trauma.[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

Bone windowing can help to identify fractures and intracranial air. Brain windowing aids in the identification of haematomas and brain swelling. Subdural fluid collections are usually crescentic in shape, unlike epidural haematomas, which are lenticular and typically do not cross suture lines.[57]Schweitzer AD, Niogi SN, Whitlow CT, et al. Traumatic brain injury: imaging patterns and complications. Radiographics. 2019 Oct;39(6):1571-95.

https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.2019190076?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31589576?tool=bestpractice.com

Acute haematomas are hyperdense, subacute haematomas are usually hyperdense or isodense, and chronic haematomas are usually hypodense, isodense, or mixed-density.[33]Teale EA, Iliffe S, Young JB. Subdural haematoma in the elderly. BMJ. 2014 Mar 11;348:g1682.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24620354?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Alves JL, Santiago JG, Costa G, et al. A standardized classification for subdural hematomas - I. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2016 Sep;37(3):174-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27428027?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Stubbs DJ, Davies BM, Menon DK. Chronic subdural haematoma: the role of peri-operative medicine in a common form of reversible brain injury. Anaesthesia. 2022 Jan;77 Suppl 1:21-33.

https://associationofanaesthetists-publications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/anae.15583

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35001374?tool=bestpractice.com

Rarely, acute SDHs may be almost isodense relative to the brain parenchyma: for example, in the hyperacute phase in a profoundly anaemic patient, or in a patient with an arachnoid tear and a mixture of haemorrhage and CSF. The presence of midline shift, the patency of the basal cisterns, and the effacement of sulcal-gyral patterns underlying the haematoma are noted. Other intracranial haematomas, such as epidural haematomas or cerebral contusions, may be identified. Cerebral swelling may be manifested as the loss of grey-white matter distinction or gyral integrity. SDHs that have a hypodense 'swirl' inside them signify potential hyperacute haematoma with active bleeding.[60]Greenberg J, Cohen WA, Cooper PR. The "hyperacute" extraaxial intracranial hematoma: computed tomographic findings and clinical significance. Neurosurgery. 1985 Jul;17(1):48-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4022287?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Al-Nakshabandi NA. The swirl sign. Radiology. 2001 Feb;218(2):433.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11161158?tool=bestpractice.com

Assessment criteria to guide imaging include the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria®, and the Canadian CT Head Rule criteria.[62]Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001 May 5;357(9266):1391-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11356436?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

For adults who have sustained a head injury, the UK NICE guidelines recommend performing CT scanning within 1 hour if any of the following risk factors are being identified in a patient:[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

Suspected open or depressed skull fracture; any sign of basilar skull fracture (e.g., haemotympanum, raccoon eyes, CSF leakage from ear or nose, Battle's sign); post-traumatic seizure; focal neurological deficit; or repeated emesis

For adults with any of the following risk factors who have experienced some loss of consciousness or amnesia since the injury, NICE recommends performing a CT head scan within 8 hours of the head injury.[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

For children who have sustained a head injury and have any of the following risk factors, NICE recommends performing a CT head scan within 1 hour of the risk factor having being identified:[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, raccoon eyes, CSF leakage from the ear or nose, Battle's sign)

For children aged under 1 year, the presence of bruising, swelling, or laceration of >5 cm on the head.

For children who have sustained a head injury and have more than one of the following risk factors (and none of those listed immediately above), NICE recommends performing a CT head scan within 1 hour of the risk factors having being identified:[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

Dangerous mechanism of injury (high-speed road traffic accident either as pedestrian, cyclist, or vehicle occupant, fall from a height of >3 meters, high-speed injury from a projectile or other object)

For both adults and children on anticoagulant or antiplatelet treatment (excluding aspirin monotherapy) who have sustained a head injury and who have no other indications for a CT head scan, NICE recommends performing a CT scan of the brain within 8 hours of injury or within the hour if they present more than 8 hours after the injury.[63]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Head injury: assessment and early management. May 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng232

The predictive value of many of the above UK NICE criteria were confirmed in one meta-analysis of 71 studies, which showed that seizure, persistent vomiting, and coagulopathy all significantly predicted positive head CT findings in patients with mild brain injury.[64]Pandor A, Harnan S, Goodacre S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical characteristics for identifying CT abnormality after minor brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2012 Mar 20;29(5):707-18.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21806474?tool=bestpractice.com

American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria® state that:[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

The Canadian CT Head Rule is a clinical decision rule derived and validated in adults with minor head injuries. It states that a CT of the head is required in patients with minor head injuries only if they have any of the following:[62]Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001 May 5;357(9266):1391-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11356436?tool=bestpractice.com

[

Canadian Head CT Rule

Opens in new window

]

Glasgow coma score <15 at 2 hours after injury

Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

Any sign of a basal skull fracture

Two or more episodes of vomiting after the injury

Age 65 years or over

Amnesia of the period before the injury of 30 minutes or longer

Dangerous mechanism of injury (pedestrian hit by a vehicle, ejection from a vehicle, fall from ≥3 feet or down ≥5 stairs)

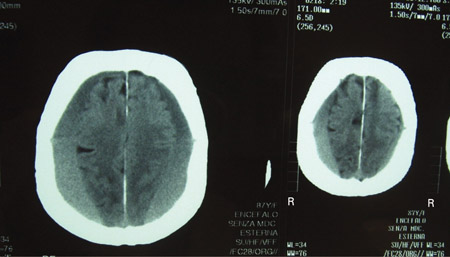

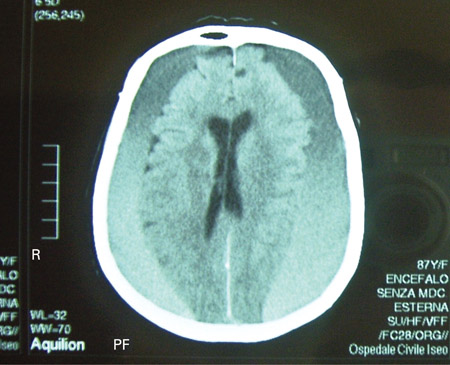

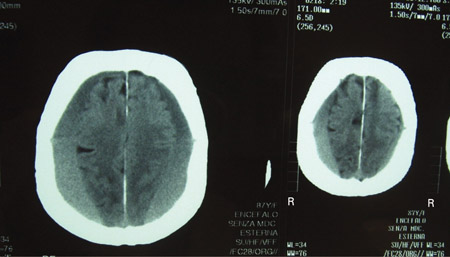

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the brain of an 80-year-old man with a gait disorder and a progressive cognitive impairment dating back about 6 months, showing a bilateral chronic subdural haematoma up to the convexityAdapted from BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0130 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scans of the brain of an 80-year-old man with a gait disorder and a progressive cognitive impairment dating back about 6 months, showing a bilateral chronic subdural haematoma up to the convexityAdapted from BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0130 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scans of the brain of an 80-year-old man with a gait disorder and a progressive cognitive impairment dating back about 6 months, showing a bilateral chronic subdural haematoma up to the convexityAdapted from BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0130 [Citation ends].

MRI of the brain

While CT is considered the first-line imaging modality for suspected intracranial injury, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful when there are persistent neurological deficits that remain unexplained after CT, especially in the subacute or chronic phase or in the absence of trauma history.[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI has superior sensitivity relative to CT for most acute intracranial findings, including small brain contusions, small extra-axial haematomas and diffuse axonal injury.[49]American College of Surgeons. Best practice guidelines: the management of traumatic brain injury. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.facs.org/media/vgfgjpfk/best-practices-guidelines-traumatic-brain-injury.pdf

[65]Griffin AD, Turtzo LC, Parikh GY, et al. Traumatic microbleeds suggest vascular injury and predict disability in traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2019 Nov 1;142(11):3550-64.

https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/142/11/3550/5581280

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31608359?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Yuh EL, Mukherjee P, Lingsma HF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging improves 3-month outcome prediction in mild traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2013 Feb;73(2):224-35.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4060890

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23224915?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI may identify differential diagnoses (e.g., lymphoma, metastasis, sarcoma, infection). Many other pathologies involving the leptomeninges or subdural space can mimic the appearance of SDHs on CT. One review found the most common pathologies mimicking SDH to be lymphoma (29%), metastasis (21%), sarcoma (15%), infection (8%), and autoimmune disorders (8%).[56]Catana D, Koziarz A, Cenic A, et al. Subdural hematoma mimickers: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2016 Sep;93:73-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27268313?tool=bestpractice.com

In nearly 80% of these cases, there was no history of trauma and most presented with a history of progressive headache. With this in mind, additional imaging such as MRI may be considered in patients presenting with an atraumatic history, progressive headache, and possible SDH on CT. In addition, MRI may identify incidental haematomas in patients being evaluated for neurological complaints. Typically, acute haematomas are isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images. Subacute haematomas are usually hyperintense on T1-weighted images and either hypointense or hyperintense on T2-weighted images (dependent on age of haematoma). Chronic SDHs are hypointense on both T1- and T2-weighted images.

When SDH is identified by CT in children with intentional brain injury, subsequent MRI will disclose additional abnormalities in approximately 25% of those imaged.[67]Kemp AM, Rajaram S, Mann M, et al; Welsh Child Protection Systematic Review Group. What neuroimaging should be performed in children in whom inflicted brain injury (iBI) is suspected? A systematic review. Clin Radiol. 2009 May;64(5):473-83.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19348842?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI may be indicated as a follow-up study when there are persistent neurological deficits that remain unexplained after a head CT.[48]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging; Shih RY, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® head trauma: 2021 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5S):S13-36.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00025-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958108?tool=bestpractice.com

Special diagnostic situations

Bilateral SDHs are common, comprising up to 24% of observed chronic SDHs.[3]Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Apr;24(2):294-307.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399248?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Andersen-Ranberg NC, Poulsen FR, Bergholt B, et al. Bilateral chronic subdural hematoma: unilateral or bilateral drainage? J Neurosurg. 2017 Jun;126(6):1905-11.

http://thejns.org/doi/full/10.3171/2016.4.JNS152642

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27392267?tool=bestpractice.com

They can present with mixed patterns: bilateral acute or chronic SDHs or a combination, with acute on one side and chronic on the other. When equal in size, the increase in pressure associated with each subdural is equal, so there is minimal or no midline shift.[3]Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Apr;24(2):294-307.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399248?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnostically this can be challenging, especially when both haematomas are subacute in age and isodense on CT.[3]Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Apr;24(2):294-307.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399248?tool=bestpractice.com

As the brain parenchyma is compressed bilaterally, the direction of the mass effect trends away from lateral shifts (i.e., subfalcine herniation) and towards downwards shifts and central herniation, a potentially fatal complication if not diagnosed and corrected in a timely fashion.[3]Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016 Apr;24(2):294-307.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26399248?tool=bestpractice.com

An epidural haematoma may be present on the contralateral side to SDH. Although rare, this is a potentially life-threatening situation, and a small epidural haematoma contralateral to an acute SDH can rapidly expand when the compressive force of the SDH is relieved by surgical evacuation.[69]Su TM, Lee TH, Chen WF, et al. Contralateral acute epidural hematoma after decompressive surgery of acute subdural hematoma: clinical features and outcome. J Trauma. 2008 Dec;65(6):1298-302.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19077617?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Mohindra S, Mukherjee KK, Gupta R, et al. Decompressive surgery for acute subdural haematoma leading to contralateral extradural haematoma: a report of two cases and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2005 Dec;19(6):490-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16574562?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial recognition is therefore important. Most epidural haematomas are associated with skull fractures coursing through the foramen spinosum, where the middle meningeal artery is injured.[57]Schweitzer AD, Niogi SN, Whitlow CT, et al. Traumatic brain injury: imaging patterns and complications. Radiographics. 2019 Oct;39(6):1571-95.

https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.2019190076?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31589576?tool=bestpractice.com

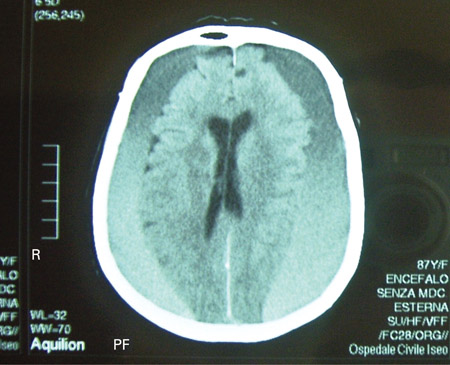

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scans of the brain of an 80-year-old man with a gait disorder and a progressive cognitive impairment dating back about 6 months, showing a bilateral chronic subdural haematoma up to the convexityAdapted from BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0130 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scans of the brain of an 80-year-old man with a gait disorder and a progressive cognitive impairment dating back about 6 months, showing a bilateral chronic subdural haematoma up to the convexityAdapted from BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06.2008.0130 [Citation ends].