Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is an obstetric emergency. Early diagnosis relies on accurate quantification of blood loss as well as frequent assessment of patient-specific risk factors, vital signs, and clinical symptoms and signs of haemorrhage.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;126(1):155-62.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2015/07000/national_partnership_for_maternal_safety_.22.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26241269?tool=bestpractice.com

The goal is to recognise PPH before any deterioration in vital signs and ensure timely intervention to control blood loss.

Early identification of high-risk patients during the antenatal period is vital in mitigating potential delays in delivering appropriate care and enabling swift responses during critical situations, thereby fostering improved maternal outcomes.

Since derangements of vital signs may only become apparent in later stages of PPH, continued meticulous assessment of ongoing blood loss is paramount.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Muñoz M, Stensballe J, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. A NATA consensus statement. Blood Transfus. 2019 Mar;17(2):112-36.

https://www.bloodtransfusion.it/bt/article/view/243

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30865585?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care. Nov 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng235

Primary PPH occurs within 24 hours of delivery and accounts for the vast majority of cases. Secondary PPH occurs >24 hours and up to 12 weeks postpartum and accounts for 1% to 2% of cases.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Make a clinical diagnosis of primary PPH based on an estimated blood loss (EBL) ≥500 mL within 24 hours of birth.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. 2012 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548502

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23586122?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Muñoz M, Stensballe J, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. A NATA consensus statement. Blood Transfus. 2019 Mar;17(2):112-36.

https://www.bloodtransfusion.it/bt/article/view/243

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30865585?tool=bestpractice.com

Be aware that the degree of EBL that warrants a diagnosis of primary PPH varies between guidelines. Check your local protocol.

Primary PPH was traditionally defined as EBL >1000 mL following caesarean delivery or >500 mL after a vaginal birth.[1]Escobar MF, Nassar AH, Theron G, et al. FIGO recommendations on the management of postpartum hemorrhage 2022. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022 Mar;157 Suppl 1(suppl 1):3-50.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.14116

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35297039?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Hunt BJ, Allard S, Keeling D, et al. A practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage. Br J Haematol. 2015 Sep;170(6):788-803.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjh.13580

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26147359?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines from the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) define primary PPH as the loss of ≥500 mL from the genital tract within 24 hours of birth.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

This definition is endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO).[5]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. 2012 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548502

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23586122?tool=bestpractice.com

By contrast, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) now endorses the reVITALIZE criteria for diagnosing primary PPH.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

These criteria define primary PPH as an EBL ≥1000 mL regardless of mode of delivery OR any volume of blood loss accompanied by signs and symptoms of hypovolaemia within 24 hours of birth.[6]Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jul;124(1):150-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24901267?tool=bestpractice.com

These updated diagnostic criteria are intended to promote early detection of PPH by tackling visual underestimation of EBL and placing equal focus on clinical symptoms and signs of haemorrhage.[1]Escobar MF, Nassar AH, Theron G, et al. FIGO recommendations on the management of postpartum hemorrhage 2022. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022 Mar;157 Suppl 1(suppl 1):3-50.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.14116

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35297039?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jul;124(1):150-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24901267?tool=bestpractice.com

Ensure your assessment of PPH incorporates both EBL and clinical signs/symptoms of blood loss. Do not rely solely on either alone.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Muñoz M, Stensballe J, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. A NATA consensus statement. Blood Transfus. 2019 Mar;17(2):112-36.

https://www.bloodtransfusion.it/bt/article/view/243

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30865585?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Andrikopoulou M, D'Alton ME. Postpartum hemorrhage: early identification challenges. Semin Perinatol. 2019 Feb;43(1):11-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30503400?tool=bestpractice.com

Be aware that assessment of vital signs remains a crucial element in early detection of PPH since visual estimation of blood loss often underestimates the extent of haemorrhage.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

The following are all signs of acute blood loss: tachycardia (heart rate >100 beats per minute); hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mmHg); tachypnoea (respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute); decreased urine output; decreased pulse pressure (the difference between systolic and diastolic pressures: normally 35-45 mmHg).[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jul;124(1):150-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24901267?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]American College of Surgeons Trauma Committee. Advanced trauma life support for doctors. 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2018.

https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications/news-and-articles/bulletin/2018/06/atls-10th-edition-offers-new-insights-into-managing-trauma-patients/

Conversely, if PPH is clinically suspected based on EBL, start immediate treatment even if the patient has normal vital signs.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Andrikopoulou M, D'Alton ME. Postpartum hemorrhage: early identification challenges. Semin Perinatol. 2019 Feb;43(1):11-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30503400?tool=bestpractice.com

The association between vital sign thresholds and degree of haemorrhage is more variable in obstetric patients compared with the general adult population because of the physiological increase in circulating blood volume.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

Derangements of vital signs are often a late manifestation of significant blood volume loss and hypovolaemic shock.[73]Guly HR, Bouamra O, Little R, et al. Testing the validity of the ATLS classification of hypovolaemic shock. Resuscitation. 2010 Sep;81(9):1142-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20619954?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Pacagnella RC, Souza JP, Durocher J, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between blood loss and clinical signs. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57594.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0057594

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23483915?tool=bestpractice.com

In pregnancy, traditional signs of hypovolaemia such as heart rate and blood pressure are normally maintained in the normal range until blood loss exceeds 1000 mL; tachycardia, tachypnoea, and a slight fall in SBP occur with blood loss of 1000-1500 mL; a SBP <80 mmHg, associated with worsening tachycardia, tachypnoea, and altered mental state, usually indicates a PPH >1500 mL.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Muñoz M, Stensballe J, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. A NATA consensus statement. Blood Transfus. 2019 Mar;17(2):112-36.

https://www.bloodtransfusion.it/bt/article/view/243

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30865585?tool=bestpractice.com

Various maternal early warning scores exist and can provide an obstetric-specific set of abnormal parameters that indicate the need for urgent bedside evaluation to identify and recognise obstetric emergencies, including haemorrhage. Check your local protocol for details of which score to use.

Examples of maternal early warning scores include:

NHS England’s national Maternity Early Warning Score (MEWS), which started roll-out in 2023 to replace a variety of modified scores used in different institutions.[75]Health Innovation Oxford & Thames Valley Patient Safety. National Maternity Early Warning Score (MEWS) tool. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.patientsafetyoxford.org/clinical-safety-programmes/safety-in-maternity/national-maternity-early-warning-score-mews-tool

The scoring system and response triggers are summarised in the diagrams below.[76]NHS England National Patient Safety Improvement Programme. Early recognition and management of deterioration of women and babies. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.patientsafetyoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Early-recognition-and-management-of-deterioration-in-women-and-babies-.pdf

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: NHS England Maternity Early Warning ScoreNHS England. National Patient Safety Improvement Programmes: early Recognition and Management of Deterioration of Women and Babies (https://www.patientsafetyoxford.org); used with permission [Citation ends].

Scotland has its own national Maternity Early Warning System.[77]Health Improvement Scotland. Scottish Patient Safety Programme. The Scottish Maternity Early Warning System (MEWS) [internet publication].

https://ihub.scot/improvement-programmes/scottish-patient-safety-programme-spsp/maternity-and-children-quality-improvement-collaborative-mcqic/maternity-care/scottish-maternity-early-warning-system-mews

In the US, the Maternal Early Warning Criteria encompass changes in blood pressure (systolic or diastolic), heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, urine output, and maternal confusion or unresponsiveness.[78]Mhyre JM, D'Oria R, Hameed AB, et al. The maternal early warning criteria: a proposal from the national partnership for maternal safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014 Nov-Dec;43(6):771-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25203897?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, the shock index (SI) can serve as a predictive indicator of haemodynamic changes resulting from acute blood loss, even when blood pressures remain within the normal range.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Pacagnella RC, Souza JP, Durocher J, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between blood loss and clinical signs. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57594.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0057594

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23483915?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Nathan HL, El Ayadi A, Hezelgrave NL, et al. Shock index: an effective predictor of outcome in postpartum haemorrhage? BJOG. 2015 Jan;122(2):268-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25546050?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]El Ayadi AM, Nathan HL, Seed PT, et al. Vital sign prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in women with hypovolemic shock: the role of shock index. PLoS One. 2016 Feb 22;11(2):e0148729.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0148729

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26901161?tool=bestpractice.com

The SI is calculated by dividing the maternal heart rate by the SBP.

SI values above 0.9 have been associated with an increased risk of requiring massive transfusion, admission to the intensive care unit, and adverse outcomes related to PPH.

Risk factors

Consider the following key risk factors for PPH based on the patient's history and clinical course: placenta praevia/low lying placenta; placenta accreta spectrum; thrombocytopenia; active bleeding during labour and delivery; maternal coagulopathy; history of PPH in prior delivery; prior caesarean delivery, uterine surgery, or multiple laparotomies; and current use of therapeutic anticoagulation.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Safe Motherhood Initiative: obstetric hemorrhage bundle [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative/obstetric-hemorrhage

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Be aware that many birthing patients who experience PPH do not have any risk factors.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

It is important to assess risk on an ongoing basis both antenatally and upon admission, with adjustments made as additional risk factors emerge during labour or the postpartum period.[52]Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;126(1):155-62.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2015/07000/national_partnership_for_maternal_safety_.22.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26241269?tool=bestpractice.com

Secondary PPH

Secondary PPH is defined as excessive bleeding that occurs more than 24 hours after delivery and up to 12 weeks postpartum.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

It may be associated with: subinvolution of the placental site; retained products of conception; infection (e.g., endometritis); inherited coagulation defects (e.g., factor deficiency such as von Willebrand).[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

In some cases, secondary PPH may be the first presentation of a bleeding disorder.

Strongly suspect endometritis as the cause if the woman presents with uterine tenderness and a low-grade fever or other signs of infection.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Ensure a meticulous physical examination of the uterus, cervix, vagina, vulva, and perineum to facilitate an accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment of the underlying cause of PPH.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

Be aware of the most common causes of PPH, which are classified by the 'four Ts' mnemonic:[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

Tone - uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH, accounting for approximately 70% to 80% of cases.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

It can be associated with intrapartum infection (chorioamnionitis or endometritis).[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Trauma - is the second most common cause of PPH, present in 20% to 30% of cases.[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

Maternal trauma is indicated by the presence of obstetric lacerations, expanding haematomas, or suspected uterine rupture.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

Tissue - retained placenta/membrane or placenta accreta spectrum is the third most common cause of PPH, present in 10% of cases.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

Thrombin - acquired or inherited coagulopathy accounts for <1% of cases of PPH.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

Note that more than one of the above causes can be present in any individual case of PPH.

Suspect uterine atony first as the most likely underlying aetiology of PPH.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

However, if bleeding is ongoing and uncontrolled, do not delay the decision to move the patient to the operating room for better visualisation and/or administration of anaesthesia as a traumatic cause may be present.

Perform a bimanual examination with abdominal fundal palpation to evaluate the tone of the uterus.[5]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. 2012 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548502

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23586122?tool=bestpractice.com

A soft, poorly contracted (boggy) uterus above the level of the umbilicus despite uterine massage is diagnostic for uterine atony.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

Uterine rupture may be diagnosed postpartum through palpation of a uterine defect on bimanual examination. Note that the most common prior intrapartum symptoms associated with uterine rupture include acute-onset persistent abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, tachysystole on tocometry, loss of fetal station, and/or a non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing in the setting of a prior uterine scar.[81]Guiliano M, Closset E, Therby D, et al. Signs, symptoms and complications of complete and partial uterine ruptures during pregnancy and delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014 Aug;179:130-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24965993?tool=bestpractice.com

If the uterine fundus cannot be palpated during a PPH, consider evaluating for uterine inversion, as incomplete or partial uterine inversion may not be immediately recognised on initial examination. A mass may or may not be palpated within the uterus, or visualised protruding from the vagina, representing the uterine fundus. These patients may experience significant shock or hypotension out of proportion to the degree of blood loss, due to vasovagal stimulation.[82]Gilmandyar D, Thornburg LL. Surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Semin Perinatol. 2019 Feb;43(1):27-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30578144?tool=bestpractice.com

Ensure a thorough examination of the abdomen and pelvis that allows for proper visualisation of the cervix and the entire length of the vaginal walls.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Muñoz M, Stensballe J, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, et al. Patient blood management in obstetrics: prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. A NATA consensus statement. Blood Transfus. 2019 Mar;17(2):112-36.

https://www.bloodtransfusion.it/bt/article/view/243

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30865585?tool=bestpractice.com

A detailed pelvic examination is required to identify unrepaired cervical, sulcal, or perineal lacerations, as well as expanding pelvic haematomas. Early intervention is paramount to prevent worsening of PPH.

It is important to note that PPH resulting from some forms of trauma (e.g., cervical or high vaginal lacerations) may only be detected during an examination under anaesthesia in the operating room.[83]Widmer M, Piaggio G, Hofmeyr GJ, et al. Maternal characteristics and causes associated with refractory postpartum haemorrhage after vaginal birth: a secondary analysis of the WHO CHAMPION trial data. BJOG. 2020 Apr;127(5):628-34.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.16040

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31808245?tool=bestpractice.com

Assess for retained products of conception, which complicates approximately 2% to 3% of all births.[84]Cheung WM, Hawkes A, Ibish S, et al. The retained placenta: historical and geographical rate variations. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(1):37-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21280991?tool=bestpractice.com

Retained placental tissue is diagnosed with careful bimanual examination upon postpartum palpation of placental tissue or membranes within the uterine cavity. Bedside ultrasonography can be used to assess the endometrial stripe for the presence of intrauterine placental tissue.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

Inspect the placenta itself to ensure intact placental delivery, and to assess for the presence of missing placental tissue or membranes.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorder (placenta accreta, increta, or percreta) may have been diagnosed antenatally on ultrasound and appropriate preparations for delivery should have been made. Have a high suspicion for PAS disorder in any case of morbidly adherent placenta suspected intraoperatively, an inability of the placenta to separate after delivery, or the presence of adherent portions of placental tissue despite manual removal.

In patients with refractory PPH, a laparotomy may be performed to further evaluate the pelvic and abdominal organs and to identify concealed haemorrhage sources such as broad ligament and retroperitoneal haematomas.[82]Gilmandyar D, Thornburg LL. Surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Semin Perinatol. 2019 Feb;43(1):27-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30578144?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial investigations

Use an objective method to measure blood loss (e.g., by weighing blood-soaked drapes or surgical sponges).[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

Weighing blood-soaked drapes or sponges is a more precise and objective approach that minimizes the risk of underestimating blood loss and facilitates early identification and intervention for PPH.[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Toledo P, McCarthy RJ, Hewlett BJ, et al. The accuracy of blood loss estimation after simulated vaginal delivery. Anesth Analg. 2007 Dec;105(6):1736-40.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2007/12000/the_accuracy_of_blood_loss_estimation_after.37.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18042876?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Patel A, Goudar SS, Geller SE, et al. Drape estimation vs. visual assessment for estimating postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006 Jun;93(3):220-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16626718?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Al Kadri HM, Al Anazi BK, Tamim HM. Visual estimation versus gravimetric measurement of postpartum blood loss: a prospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011 Jun;283(6):1207-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20508942?tool=bestpractice.com

Visual estimation can result in underestimation of blood loss by 33% to 50%, particularly when large volumes are lost.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;126(1):155-62.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2015/07000/national_partnership_for_maternal_safety_.22.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26241269?tool=bestpractice.com

Objective measurement of cumulative quantitative blood loss (QBL) - including the use of under-buttock drapes during vaginal births and real-time weight measurements of blood-soaked materials - is advocated by the WHO and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) as an essential part of an obstetric haemorrhage detection and management bundle.[12]International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Uterine atony and uterotonics in postpartum haemorrhage. October 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.figo.org/resources/figo-statements/uterine-atony-and-uterotonics-postpartum-haemorrhage

[55]Lyndon A. Cumulative quantitative assessment of blood loss. CMQCC Obstet Hemorrhage Toolkit Version. 2015;2:80-5.[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

Some studies have cast doubt on the effectiveness of QBL measurements in preventing PPH or improving maternal outcomes.[88]Zhang WH, Deneux-Tharaux C, Brocklehurst P, et al. Effect of a collector bag for measurement of postpartum blood loss after vaginal delivery: cluster randomised trial in 13 European countries. BMJ. 2010 Feb 1;340:c293.

https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c293.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20123835?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Hancock A, Weeks AD, Lavender DT. Is accurate and reliable blood loss estimation the 'crucial step' in early detection of postpartum haemorrhage: an integrative review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015 Sep 28;15:230.

https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-015-0653-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26415952?tool=bestpractice.com

There is no robust evidence that specifically demonstrates a reliable correlation between QBL measurements and postpartum haemoglobin measurements.[90]Hamm RF, Wang E, Romanos A, et al. Implementation of quantification of blood loss does not improve prediction of hemoglobin drop in deliveries with average blood loss. Am J Perinatol. 2018 Jan;35(2):134-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28838005?tool=bestpractice.com

The E-MOTIVE trial, published in 2023, assessed use of a calibrated drape for early detection of excessive blood loss following vaginal birth among 210,132 women in four African nations. Use of the drapes triggered an immediate treatment bundle for any woman with blood loss of ≥500 mL (as indicated by a red action line on the drapes) or with blood loss ≥300 mL (yellow warning line) together with hypotension or tachycardia. This combined PPH early detection and treatment bundle was associated with a 60% reduction in the composite primary outcome of severe PPH (blood loss ≥1000 mL), or laparotomy or maternal death from PPH (risk ratio 0.40, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.50; P <0.001) when compared with usual care.[91]Gallos I, Devall A, Martin J, et al. Randomized trial of early detection and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jul 6;389(1):11-21.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2303966

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37158447?tool=bestpractice.com

In response to the E-MOTIVE findings, the WHO commissioned a systematic review on methods to assess postpartum blood loss. This led to a recommendation to use an objective method to quantify blood loss in all women giving birth, such as calibrated drapes for those having vaginal birth.[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

The WHO highlighted that to be effective in improving outcomes, objective approaches to quantifying blood loss must be combined with a standardised protocol to ensure prompt initiation of treatment immediately on detection of PPH.[71]World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on the assessment of postpartum blood loss and use of a treatment bundle for postpartum haemorrhage. 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240085398

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38170808?tool=bestpractice.com

In guidance that predates publication of the E-MOTIVE trial results and the WHO recommendation, the UK RCOG states that use of blood collection drapes for vaginal deliveries and the weighing of swabs is an option to address visual underestimation of blood loss.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

The ACOG has published tips for quantification of blood loss following vaginal and caesarean delivery.[92]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Quantitative blood loss in obstetric hemorrhage: ACOG Committee opinion, number 794. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Dec;134(6):e150-6.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/fulltext/2019/12000/quantitative_blood_loss_in_obstetric_hemorrhage_.40.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31764759?tool=bestpractice.com

Order a blood test in all patients with suspected PPH including full blood count plus blood type and cross-match.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care. Nov 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng235

Send a stat blood sample for type and cross-match for any patient with suspected PPH, to facilitate timely administration of blood product replacement, if indicated.

Notify the blood bank so that at least 2 units of blood can be type and cross-matched for the patient.[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Bear in mind that on admission to labour and delivery, an initial type and screen should have been ordered for any patient deemed to be at medium risk for PPH and a type and cross should have been sent for any patient deemed high risk.[7]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Safe Motherhood Initiative: obstetric hemorrhage bundle [internet publication].

https://www.acog.org/community/districts-and-sections/district-ii/programs-and-resources/safe-motherhood-initiative/obstetric-hemorrhage

[8]Goffman D, Ananth CV, Fleischer A, et al. The New York State Safe Motherhood Initiative: early impact of obstetric hemorrhage bundle implementation. Am J Perinatol. 2019 Nov;36(13):1344-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30609429?tool=bestpractice.com

Request coagulation profile analysis in any case of significant PPH.[2]Hunt BJ, Allard S, Keeling D, et al. A practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage. Br J Haematol. 2015 Sep;170(6):788-803.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjh.13580

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26147359?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care. Nov 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng235

Early identification of coagulation abnormalities can aid in the timely administration of appropriate blood products or adjunctive medical therapies.[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Thrombin (clotting factor deficiency) is the underlying cause of <1% of cases of PPH.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Mar 15;75(6):875-82.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2007/0315/p875.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390600?tool=bestpractice.com

Fibrinogen levels increase during pregnancy to around 4-6 g/L by the time of delivery, hence a level of 2-3 g/L (which would be reassuring in a non-pregnant patient) indicates significant blood loss in PPH.[2]Hunt BJ, Allard S, Keeling D, et al. A practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage. Br J Haematol. 2015 Sep;170(6):788-803.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjh.13580

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26147359?tool=bestpractice.com

If disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or another acquired or inherited coagulopathy is suspected, evaluation of the patient's coagulation status is especially crucial.[21]Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 29;384(17):1635-45.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10181876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33913640?tool=bestpractice.com

Request serum profiles to assess prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalised ratio (INR), and fibrinogen to confirm the diagnosis.

Further investigations

Uterine ultrasound can be used to assess for retained products of conception, although the diagnosis of retained products is unreliable.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

[93]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: postpartum hemorrhage. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3113019/Narrative

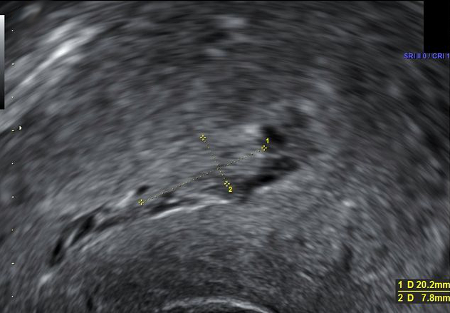

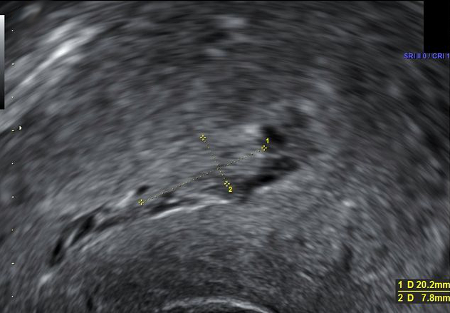

Bedside ultrasonography can be used to assess the endometrial stripe for an echogenic mass, strongly indicating the presence of intrauterine placental tissue.[3]Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28937571?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound is particularly important in investigation of secondary PPH, which can be caused by retained products of conception.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ultrasound image showing retained product of conception within the endometrial cavity (measuring 20 x 8mm) in a woman with secondary PPH. The image was taken on day 22 post-deliveryDu R, et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2021;14:e245009; used with permission [Citation ends].

In haemodynamically stable patients in whom conventional medical treatment has failed to stop the bleeding, further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast can be considered, particularly in suspected intra-abdominal haemorrhage or post-surgical complications.[93]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: postpartum hemorrhage. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/3113019/Narrative

In women presenting with secondary PPH, ensure an assessment of vaginal microbiology with high vaginal and endocervical swabs.[4]Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 52. BJOG. 2017 Apr;124(5):e106-49.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14178

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27981719?tool=bestpractice.com

Emerging investigations

Thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) are rapid point-of-care tests that can aid in the evaluation of coagulopathy. They are increasingly used in obstetric facilities to guide transfusion needs and elucidate the underlying factors contributing to coagulopathy in patients experiencing PPH.[94]Holcomb JB, Minei KM, Scerbo ML, et al. Admission rapid thrombelastography can replace conventional coagulation tests in the emergency department: experience with 1974 consecutive trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256(3):476-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22868371?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Haas T, Spielmann N, Mauch J, et al. Comparison of thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) with standard plasmatic coagulation testing in paediatric surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2012 Jan;108(1):36-41.

https://www.bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(17)32513-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22086509?tool=bestpractice.com

Standard coagulation assays performed on plasma have limitations in assessing clinically significant coagulopathy caused by ongoing blood loss and specific coagulation factors such as factor XIII, platelet function, and fibrinolytic system activity.[94]Holcomb JB, Minei KM, Scerbo ML, et al. Admission rapid thrombelastography can replace conventional coagulation tests in the emergency department: experience with 1974 consecutive trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256(3):476-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22868371?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Haas T, Spielmann N, Mauch J, et al. Comparison of thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) with standard plasmatic coagulation testing in paediatric surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2012 Jan;108(1):36-41.

https://www.bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(17)32513-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22086509?tool=bestpractice.com

TEG and ROTEM® offer distinct advantages over standard assays by enabling the evaluation of coagulation using whole blood, including assessment of platelet function and the timing and extent of fibrinolysis. This rapid and precise detection of coagulation abnormalities can be invaluable in cases of ongoing PPH.[96]Hunt H, Stanworth S, Curry N, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) for trauma induced coagulopathy in adult trauma patients with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 16;(2):CD010438.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010438.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25686465?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Wikkelsø A, Wetterslev J, Møller AM, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to monitor haemostatic treatment versus usual care in adults or children with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 22;(8):CD007871.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007871.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27552162?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Da Luz LT, Nascimento B, Shankarakutty AK, et al. Effect of thromboelastography (TEG®) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) on diagnosis of coagulopathy, transfusion guidance and mortality in trauma: descriptive systematic review. Crit Care. 2014 Sep 27;18(5):518.

https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-014-0518-9

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25261079?tool=bestpractice.com

However, the use of TEG and ROTEM® is currently limited by the absence of standardised normal reference ranges, making it challenging to interpret results and compare them between different healthcare settings. Variations in baseline parameters for specific obstetric populations further contribute to the complexity of accurate interpretation.[96]Hunt H, Stanworth S, Curry N, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) for trauma induced coagulopathy in adult trauma patients with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 16;(2):CD010438.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010438.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25686465?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Wikkelsø A, Wetterslev J, Møller AM, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) or thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to monitor haemostatic treatment versus usual care in adults or children with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 22;(8):CD007871.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007871.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27552162?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Da Luz LT, Nascimento B, Shankarakutty AK, et al. Effect of thromboelastography (TEG®) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) on diagnosis of coagulopathy, transfusion guidance and mortality in trauma: descriptive systematic review. Crit Care. 2014 Sep 27;18(5):518.

https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-014-0518-9

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25261079?tool=bestpractice.com

[99]Lee J, Wyssusek KH, Kimble RMN, et al. Baseline parameters for rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) in healthy pregnant Australian women: a comparison of labouring and non-labouring women at term. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020 Feb;41:7-13.

https://www.obstetanesthesia.com/article/S0959-289X(19)30558-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31831279?tool=bestpractice.com

Innovative app-based techniques supported by artificial intelligence (e.g., the US Food and Drug Administration-approved Triton System™) have emerged to enhance the measurement of ongoing blood loss. Leveraging mobile monitoring capabilities, the Triton System™ captures images of blood-soaked surgical materials and employs feature extraction technology to provide accurate haemoglobin measurements.[100]Konig G, Holmes AA, Garcia R, et al. In vitro evaluation of a novel system for monitoring surgical hemoglobin loss. Anesth Analg. 2014 Sep;119(3):595-600.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2014/09000/in_vitro_evaluation_of_a_novel_system_for.15.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24806138?tool=bestpractice.com

[101]Holmes AA, Konig G, Ting V, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel system for monitoring surgical hemoglobin loss. Anesth Analg. 2014 Sep;119(3):588-94.

https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2014/09000/clinical_evaluation_of_a_novel_system_for.14.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24797122?tool=bestpractice.com

While the potential benefits of this technology are promising, its long-term efficacy in the context of obstetric care requires further evaluation.