Approach

Your Organisational Guidance

ebpracticenet urges you to prioritise the following organisational guidance:

Aanhoudende hoest bij kinderen in de eerste lijnPublished by: Werkgroep Ontwikkeling Richtlijnen Eerste Lijn (Worel)Last published: 2017La toux prolongée chez l’enfant en première ligne de soinsPublished by: Groupe de Travail Développement de recommmandations de première ligneLast published: 2017The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) 2006 guideline defines upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) as a syndrome characterised by chronic cough (i.e., present for ≥8 weeks) related to upper airway abnormalities.[1] More recent guidelines specific to UACS are lacking. The British Thoracic Society recommends diagnosing patients with chronic cough using a general approach focused on defining treatable traits of cough, rather than using terms like UACS.[6]

Central to the diagnosis is the presence of abnormal sensations arising from the throat (e.g., patients may describe something stuck in the throat). As there are no pathognomonic findings or definitive tests to establish a diagnosis, the ACCP recommends that diagnosis should be determined by considering a combination of criteria, including the history, physical exam, imaging (to exclude other causes), and, ultimately, the response to specific therapy. An empirical trial of therapy is considered to be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Improvement or resolution of cough in response to treatment is pivotal to confirming the diagnosis.[1]

History

A thorough history is an important first step in the assessment of any patient with a chronic cough. The initial approach should cover aspects common to the evaluation of any chronic cough, and the physician should first ascertain whether there are any causes that are easily remedied. The approach should also focus on identifying red-flag symptoms that warrant further work-up (e.g., haemoptysis, chest pain, persistent voice change). These symptoms should arouse suspicion for more serious conditions such as bronchiectasis, pulmonary tuberculosis, or lung cancer.

A complete drug history should be taken, as ACE inhibitors are a common cause of chronic cough.[31][32] An upper respiratory illness (e.g., common cold) is often present.

Seasonal allergen exposure may be a key trigger and should prompt investigation to determine atopic status to seasonal aeroallergens. Certain occupations have been associated with UACS. Common work exposures associated with occupational rhinitis include laboratory animal workers with allergic rhinitis from laboratory animal allergy, or non-allergic rhinitis associated with endotoxin exposure; and bakers with allergic rhinitis to wheat, egg, enzymes, or other high-molecular-weight allergens in a bakery.[30]

The character and timing of the cough along with associated features provide important clues towards the underlying cause.[33] Typically, the cough is dry and has been present for at least 8 weeks. In some patients, the cough may be minimally productive; however, a daily productive cough should prompt consideration of pulmonary or sinus pathology (e.g., bronchiectasis or rhinosinusitis).

Assess upper airway symptoms

Symptoms are generally non-specific, and many clinical features overlap with a general cough hypersensitivity syndrome. The key diagnostic feature is an unpleasant sensation in the throat. The description of this symptom can vary; however, it is typically described as an unpleasant feeling in the throat as if something is stuck or lodged there, or is tickling or irritating it. Postnasal drip is a central feature. It is often described as a feeling of mucus dripping from the back of the nose into the throat, and is commonly associated with throat-clearing maneuvers.

Patients may report a change in voice quality (e.g., dysphonia, hoarseness). This can be considered a feature of UACS; however, other causes should also be considered and ruled out. A clinically relevant overlap between disorders of laryngeal function (e.g., cough, voice disturbance, difficulty breathing air into the lungs with inspiratory stridor, swallowing difficulty) is well-recognised.[23][24][34] A thorough history should therefore explore these aspects of airway 'health'. Screening questionnaires are now available to highlight the presence of laryngeal hypersensitivity.[35]

Nasal and sinus symptoms

Careful attention should be paid to nasal and sinus symptoms in order to consider if sinus imaging or laryngoscopy is required. Features of rhinitis may coexist and include persistent clear nasal discharge, sneezing, and intermittent nasal blockage. In the context of allergic rhinitis, additional prominent features include nasal pruritus and conjunctivitis. Clinical features such as unilateral nasal symptoms, facial pain, thick green discharge, recurrent nosebleeds, or persistent loss of smell are not typical features of rhinitis and warrant further ENT assessment.[36] Loss or decreased sense of smell is associated with nasal polyps and may also indicate a higher likelihood of comorbid asthma or type 2 lower airway inflammation.[37][38]

Additional contributory factors

Gastro-oesophageal reflux may coexist with UACS.[39] Although symptoms of heartburn/indigestion may be self-reported, it is important to be aware that other features (e.g., cough with phonation, on eating, on bending over, or on first becoming ambulatory in the morning) may indicate atypical reflux as a relevant aggravating factor.

Cigarette smoking can be a cause of, or contributing factor to, chronic cough. Active smoking can complicate the evaluation of chronic cough due to UACS and the assessment of response to empirical treatment.

Physical exam

Oropharyngeal exam may reveal visible mucus and a cobblestone appearance to the posterior oropharyngeal wall and local upper airway structures. Intranasal abnormalities (e.g., crusting, mucosal oedema) or nasal disease (e.g., oedema, polyps) may be noted. Some patients with upper airway abnormalities may have an inspiratory wheeze arising from the glottis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oropharynx with evidence of generalised oedema, enlarged uvula, and some cobblestone change.Image courtesy of Mr Guri Sandhu; used with permission [Citation ends].

Investigations

There are no definitive tests; however, a trial of empirical therapy (i.e., a first-generation antihistamine plus a decongestant) has been recommended to confirm the diagnosis in the presence of a supportive history and examination, and imaging that rules out alternative diagnoses. Patients with UACS generally respond to empirical therapy and a response is required for confirmation of the diagnosis according to ACCP criteria.[1]

The following tests should be ordered in all patients to rule out other causes:

FBC: may show eosinophilia, which most commonly suggests allergy

Chest x-ray: may show pulmonary pathology

Spirometry: may show obstruction/airway disease

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO): may indicate the presence of type 2 inflammation in the lower airways. See Asthma in adults.

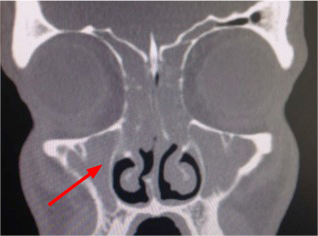

Other tests depend on the patient history, but may include the following:[23][40][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT sinus demonstrating opacification.Image courtesy of Mr Hesham Saleh; used with permission [Citation ends].

Serum IgE level: elevated IgE indicates atopy

Specific aeroallergen radioallergosorbent test (RAST): positive RAST indicates atopy

Peak expiratory flow (PEF): may show obstruction/airway disease

Chest computed tomography (CT) with or without contrast: may be appropriate for patients with inconclusive chest x-ray

Sinus CT: may show evidence of sinus disease

Direct nasolaryngoscopy: used to identify structural or movement (e.g., paradoxical closure on inspiration) abnormalities, evidence of reflux change, and visible postnasal drip. When performed with provocation (e.g., exposure to perfume or exercise) can provide evidence of inducible laryngeal obstruction, which is sometimes termed vocal cord dysfunction.

In UACS, the results of all tests should be normal unless a coexisting condition is present or the cough is due to another aetiology.

Bronchial challenge tests are used to establish a diagnosis of asthma. However, they are increasingly being used to measure extrathoracic hyper-responsiveness (i.e., laryngeal dysfunction). In this context, one series showed that a positive result was common in patients with chronic cough.[41] The outcome parameter when testing for UACS (inspiratory flows based on the reference provided) is not the same as for asthma (FEV₁). Further work is needed to establish the clinical value of this test, and it is not widely used at present in patients with isolated chronic cough unless there are indications of asthma, such as a history of breathlessness or wheezing.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer