Clinical features

RSV infection almost always produces symptoms. The severity varies depending on the patient's age, history of previous infection, and comorbidities.[44]Henderson FW, Collier AM, Clyde WA Jr., et al. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity: a prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979 Mar 8;300(10):530-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/763253?tool=bestpractice.com

[90]Welliver RC. Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. J Pediatr. 2003 Nov;143(5 Suppl):S112-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615709?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinicians should determine whether the patient is at high risk for developing severe illness, including the following factors:[1]Bont L, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, et al. Defining the epidemiology and burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants and children in western countries. Infect Dis Ther. 2016 Sep;5(3):271-98.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5019979

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27480325?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Ricart S, Marcos MA, Sarda M, et al. Clinical risk factors are more relevant than respiratory viruses in predicting bronchiolitis severity. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013 May;48(5):456-63.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7167901

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22949404?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Anderson EJ, Carbonell-Estrany X, Blanken M, et al. Burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus disease among 33-35 weeks' gestational age infants born during multiple respiratory syncytial virus seasons. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017 Feb;36(2):160-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5242218

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27755464?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Carbonell-Estrany X, Fullarton JR, Gooch KL, et al. The influence of birth weight amongst 33-35 weeks gestational age (wGA) infants on the risk of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalisation: a pooled analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017 Jan;30(2):134-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26965584?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Mauskopf J, Margulis AV, Samuel M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations in healthy preterm infants: systematic review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Jul;35(7):e229-38.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4927309

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27093166?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Cai W, Buda S, Schuler E, et al. Risk factors for hospitalized respiratory syncytial virus disease and its severe outcomes. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020 Nov;14(6):658-70.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7578333

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32064773?tool=bestpractice.com

[91]Anderson J, Do LAH, Wurzel D, et al. Severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in preterm infants: a case of innate immaturity. Thorax. 2021 Sep;76(9):942-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33574121?tool=bestpractice.com

These patients require closer observation and are frequently admitted to the hospital.[2]Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134(5):e1474-502.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25349312?tool=bestpractice.com

Infants and young children

Infants typically present with upper respiratory tract findings such as rhinorrhoea and congestion. The physician may suspect RSV as the diagnosis when, over the next 2-4 days, the lower respiratory tract becomes involved and illness manifests as tachypnoea, cough, wheeze, prolonged expiration, and increased work of breathing.

Signs of moderate illness include hypoxaemia (oxygen saturations <90%), tachypnoea, increased work of breathing (nasal flaring, intercostal retractions, head bobbing), inadequate feeding, and dehydration. More severe cases are associated with hypoxia and respiratory failure.[2]Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134(5):e1474-502.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25349312?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Henderson FW, Collier AM, Clyde WA Jr., et al. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity: a prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979 Mar 8;300(10):530-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/763253?tool=bestpractice.com

Physicians should enquire about difficulty with feeding, malaise, and signs of otitis media, as these may also be present. Apnoea may be the sole presenting finding in very young infants (age <1 month) and may be severe enough to result in death.[92]Church NR, Anas NG, Hall CB, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-related apnea in infants: demographics and outcome. Am J Dis Child. 1984 Mar;138(3):247-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6702769?tool=bestpractice.com

Very young infants may also present with sepsis.

Older children and adults

RSV disease in older children and healthy adults is typically limited to the upper respiratory tract but may progress to tracheobronchitis.[93]Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in previously healthy working adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Sep 15;33(6):792-6.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/33/6/792.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11512084?tool=bestpractice.com

Symptoms include nasal congestion, ear and sinus involvement, productive cough, and wheezing.[93]Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in previously healthy working adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Sep 15;33(6):792-6.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/33/6/792.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11512084?tool=bestpractice.com

In young adults who are otherwise well, RSV typically presents as an upper respiratory tract infection with mild to moderate symptoms, and only very rarely causes severe disease.[94]Coultas JA, Smyth R, Openshaw PJ. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): a scourge from infancy to old age. Thorax. 2019 Oct;74(10):986-93.

https://www.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212212

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31383776?tool=bestpractice.com

Additionally, healthy children and adults may be asymptomatic facilitating the spread of infection to more vulnerable hosts.[95]Moreira LP, Watanabe ASA, Camargo CN, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus evaluation among asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects in a university hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the period of 2009-2013. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018 May;12(3):326-30.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/irv.12518

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29078028?tool=bestpractice.com

Immune deficiency, increasing age, and comorbidity

Older people, people with immune deficiency, and those with respiratory or cardiac comorbidity, are at risk of developing severe lower respiratory disease.[94]Coultas JA, Smyth R, Openshaw PJ. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): a scourge from infancy to old age. Thorax. 2019 Oct;74(10):986-93.

https://www.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212212

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31383776?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Walsh EE, Falsey AR, Hennessey PA. Respiratory syncytial and other virus infections in persons with chronic cardiopulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Sep;160(3):791-5.

http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9901004#.UlQpwlPCZgA

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10471598?tool=bestpractice.com

Among immune deficient patients, the greatest incidence of RSV infection is seen in patients receiving haematopoietic stem cell transplants and lung transplants.[30]Nam HH, Ison MG. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. BMJ. 2019 Sep 10;366:l5021.

https://www.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5021

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31506273?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with RSV receiving haematopoietic stem cell transplants develop progression from upper to lower respiratory tract infection in 40% to 60% of cases; in these patients, lower respiratory tract infection is associated with mortality rates of up to 80%.[30]Nam HH, Ison MG. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. BMJ. 2019 Sep 10;366:l5021.

https://www.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5021

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31506273?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnostic tests

Rapid point-of-care tests for the detection of RSV have a sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 99%, respectively.[97]Bruning AHL, Leeflang MMG, Vos JMBW, et al. Rapid tests for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and other respiratory viruses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 15;65(6):1026-32.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/65/6/1026/3829590

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28520858?tool=bestpractice.com

However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that the diagnosis of bronchiolitis should be established based on findings in the history and physical examination.[2]Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134(5):e1474-502.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25349312?tool=bestpractice.com

The AAP further recommends that clinicians should not routinely order laboratory or radiographical studies for diagnosis.[2]Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134(5):e1474-502.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25349312?tool=bestpractice.com

Likewise, studies in adult populations have not proved to be of benefit.[8]Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics. Red book. 32nd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP; 2021.

https://publications.aap.org/aapbooks/book/663/Red-Book-2021-Report-of-the-Committee-on

[98]Nicholson KG, Abrams KR, Batham S, et al. Randomised controlled trial and health economic evaluation of the impact of diagnostic testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae infection on the management of acute admissions in the elderly and high-risk 18- to 64-year-olds. Health Technol Assess. 2014 May;18(36):1-274, vii-viii.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24875092?tool=bestpractice.com

Nonetheless, confirming the presence of RSV may be advantageous in order to isolate and cohort patients with known infection.[99]Krasinski K, LaCourture R, Holzman RS, et al. Screening for respiratory syncytial virus and assignment to a cohort at admission to reduce nosocomial transmission. J Pediatr. 1990 Jun;116(6):894-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2348292?tool=bestpractice.com

Rapid viral testing has been shown to reduce the number of chest radiographs undertaken in the accident and emergency department, and results suggest a beneficial effect in terms of lowering antibiotic usage, although this was not statistically significant.[100]Doan Q, Enarson P, Kissoon N, et al. Rapid viral diagnosis for acute febrile respiratory illness in children in the Emergency Department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD006452.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006452.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25222468?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the effects of rapid viral detection tests for children attending emergency departments with an acute respiratory infection?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2298/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the effects of rapid viral detection tests for children attending emergency departments with an acute respiratory infection?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2298/fullShow me the answer

Testing of nasopharyngeal aspirates for RSV is available through rapid antigen testing (often available for use at the point-of-care) as well as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. PCR testing has a higher sensitivity and equivalent specificity as compared with antigen testing, especially in the adult population where antigen test sensitivity can be as low as 50%.[101]Bernstein DI, Mejias A, Rath B, et al. Summarizing study characteristics and diagnostic performance of commercially available tests for respiratory syncytial virus: a scoping literature review in the COVID-19 era. J Appl Lab Med. 2023 Mar 6;8(2):353-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9384538

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35854475?tool=bestpractice.com

Increasing availability and speed of PCR-based tests have made these more commonly used.[102]Onwuchekwa C, Moreo LM, Menon S, et al. Underascertainment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults due to diagnostic testing limitations: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2023 Jul 14;228(2):173-84.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10345483

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36661222?tool=bestpractice.com

Other testing

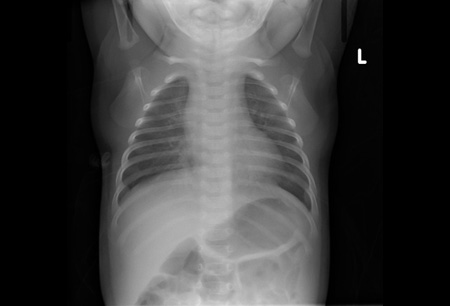

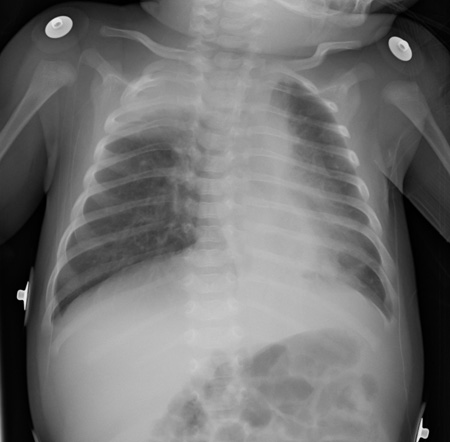

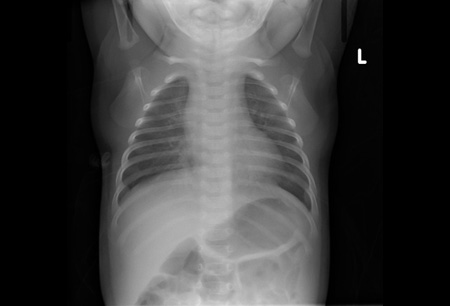

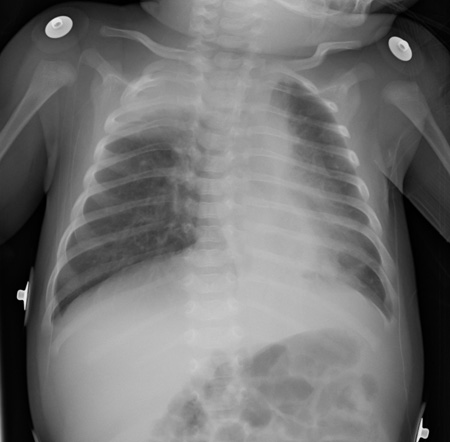

Chest radiograph may reveal atelectasis, hyperexpansion, and peribronchial cuffing.[103]Simpson W, Hacking PM, Court SD, et al. The radiological findings in respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. II: the correlation of radiological categories with clinical and virological findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1974;2(3):155-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4423578?tool=bestpractice.com

[104]Simpson W, Hacking PM, Court SD, et al. The radiological findings in respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Part I: definitions and interobserver variation in the assessment of abnormalities on the chest x-ray. Pediatr Radiol. 1974;2(2):97-100.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15822330?tool=bestpractice.com

[105]Friis B, Eiken M, Hornsleth A, et al. Chest x-ray appearances in pneumonia and bronchiolitis: correlation to virological diagnosis and secretory bacterial findings. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990 Feb;79(2):219-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2321485?tool=bestpractice.com

Interstitial infiltrates are less common.

Chest radiography should be reserved for patients with severe disease, and those who do not improve at the expected rate.[2]Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134(5):e1474-502.

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25349312?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: AtelectasisFrom the personal collections of Melvin L. Wright, DO and Giovanni Piedimonte, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Air trapping and peribronchial cuffingFrom the personal collections of Melvin L. Wright, DO and Giovanni Piedimonte, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Air trapping and peribronchial cuffingFrom the personal collections of Melvin L. Wright, DO and Giovanni Piedimonte, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends only performing a chest x‑ray if intensive care is being proposed for a baby or child. A chest x‑ray in babies or children with bronchiolitis may mimic pneumonia and should not be used to determine the need for antibiotics.[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management. Aug 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9

Full blood count and serum chemistries are not routinely helpful but may be considered in the presence of severe disease. Blood cultures are indicated if bacterial infection is suspected.

Clinically assess the hydration status of babies and children with bronchiolitis to determine the hydration requirements of the patient.[53]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management. Aug 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9

]

]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Air trapping and peribronchial cuffingFrom the personal collections of Melvin L. Wright, DO and Giovanni Piedimonte, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Air trapping and peribronchial cuffingFrom the personal collections of Melvin L. Wright, DO and Giovanni Piedimonte, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].