Approach

Presentation of group B streptococci (GBS) infection is non-specific, and there are no features that distinguish it from other bacterial infections. A thorough history is important to elucidate possible risk factors and allow appropriate microbiological sampling. A confirmed case is a clinically compatible illness with isolation of GBS from a normally sterile site.

In the US, most studies show an increased incidence of disease in black people in all age groups.[7]

History

Early-onset neonatal infection (0-6 days after delivery, normally in first 12 hours)

80% of childhood GBS infections occur in the first 7 days of life, after exposure to the bacteria during labour or before delivery, including aspiration of contaminated amniotic fluid.[22] Most infants present within 12 hours of birth.

Maternal history may include fever during labour, premature rupture of membranes, GBS bacteriuria (indicates heavy GBS colonisation), previous baby or twin sibling with GBS infection, chorioamnionitis, deficient maternal-specific immunoglobulin at term, or age <20 years. Preterm delivery is also a strong risk factor.[6][12][22][23][35]

Late-onset neonatal infection (7-89 days after delivery, normally in first 4 weeks)

Late-onset disease is often unrelated to maternal colonisation or obstetric complications.[18][45] A positive test result for GBS in the mother at birth is significantly associated with late-onset disease.[65]

The exact mechanism of acquisition for late-onset disease is not known, although nosocomial transmission has been described.[66]

Infants and children

GBS infection is less common in infants and children. Key risk factors include presence of renal disease, neurological disease, malignancy, and immunosuppression.[7]

Fever is a common presenting symptom as with any other bacterial infection.

Sepsis with unknown focus, meningitis, pneumonia, septic arthritis, and peritonitis are the most common presentations in children aged 90 days to 14 years.[7] Patients may therefore present with the following additional symptoms depending on the focus of infection: confusion (sepsis); headache, photophobia, or neck pain or stiffness (meningitis); productive cough, dyspnoea, tachypnoea, pleuritic chest pain, or increased work of breathing (pneumonia); joint erythema, swelling, or pain; decreased range of movement (septic arthritis); or abdominal pain (peritonitis).

Symptoms of meningeal inflammation are often absent in children <2 years of age.

Non-pregnant adults

Key risk factors include age >60 years, residency in nursing home, diabetes, obesity, hepatic or renal disease, placement of central venous catheter, urological disorders or urinary tract infection (UTI), breaks in skin integrity (e.g., pressure sores, ulcers), neurological disease, immunosuppression, and malignancy.[7][6][20][21][37]

Fever is a common presenting symptom as with any other bacterial infection, although it is often absent in older patients.

Cellulitis, sepsis, meningitis, and UTI are the most common presentations. Patients may therefore present with the following additional symptoms depending on the focus of infection: headache, photophobia, or neck pain or stiffness (meningitis); dysuria, frequency, urgency, haematuria, or back/flank pain (UTI); skin discomfort, erythema, warmth, tenderness, or oedema (cellulitis); or confusion (sepsis).

Less common manifestations include septic arthritis, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, sinusitis, otitis media, and intra-abdominal infection. Patients may therefore also present with the following additional symptoms depending on focus of infection: joint erythema, swelling, or pain, or a decreased range of movement (septic arthritis); productive cough, dyspnoea, tachypnoea, pleuritic chest pain, or increased work of breathing (pneumonia); nasal discharge or facial/dental pain (sinusitis); watery, mucoid, or purulent discharge from the eye, ocular tenderness, or eyelids stuck together in the morning (conjunctivitis); otalgia (otitis media); or abdominal pain, decreased bowel movements, or nausea and vomiting (intra-abdominal infection).

Pregnant women

Fever is a common presenting symptom as with any other bacterial infection.

Can produce a wide range of manifestations including UTI, chorioamnionitis, sepsis, postnatal endometritis, and postnatal wound infection. Pregnant women may therefore present with the following additional symptoms depending on the focus of infection: dysuria, frequency, urgency, haematuria, or back/flank pain (UTI); skin discomfort, erythema, warmth, tenderness, or oedema (cellulitis); confusion (sepsis); or lower abdominal pain (postnatal endometritis).

Physical examination

Early-onset neonatal infection

Manifestations of infection can be non-specific, and include grunting, pallor, or hypotonia. Respiratory distress, lethargy, irritability, and poor appetite/feeding are also non-specific markers of infection.

Neonates often present with temperature instability rather than fever.

Meningitis, sepsis, UTI, and pneumonia are the most common types of infection in this patient group. Neonates may therefore present with the following signs depending on the focus of infection: seizures, stiff neck, bulging fontanelles, or Kernig's or Brudzinski's signs (meningitis); tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea, or poor capillary refill (sepsis); suprapubic tenderness or costovertebral angle tenderness (UTI); or respiratory distress, cyanosis, nasal flaring, intercostal or subcostal indrawing, decreased breath sounds, auscultatory crackles, or pleural rub (pneumonia).

However, signs of meningeal inflammation are often absent, which is why a lumbar puncture should always be done in this patient group.

GBS infection should be suspected if there is evidence of sepsis in the infant, mother, or both.

Late-onset neonatal infection

Manifestations of infection can be non-specific, and include grunting, pallor, or hypotonia. Respiratory distress, lethargy, irritability, and poor appetite/feeding are also non-specific markers of infection.

Often characterised by fever ≥38°C (100.4°F).[65]

Meningitis is the most common infection. Neonates may therefore present with seizures, stiff neck, bulging fontanelles, or Kernig's or Brudzinski's signs.

However, signs of meningeal inflammation are often absent, which is why a lumbar puncture should always be done in this patient group.

Infants and children

Sepsis with unknown focus, meningitis, pneumonia, septic arthritis, and peritonitis are the most common presentations in children aged 90 days to 14 years.[7]

Patients may therefore present with the following signs depending on the focus of infection: seizures, stiff neck, bulging fontanelles, or Kernig's or Brudzinski's signs (meningitis); tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea, or poor capillary refill (sepsis); respiratory distress, cyanosis, nasal flaring, intercostal or subcostal indrawing, decreased breath sounds, auscultatory crackles, or pleural rub (pneumonia); hot, swollen, tender joint with joint effusion (septic arthritis); or tender rigid abdomen, guarding, rebound tenderness, or decreased or absent bowel sounds (peritonitis).

Signs of meningeal inflammation are often absent in children <2 years of age.

Non-pregnant adults

With increasing age, localising symptoms of infection may be blunted and signs of sepsis may be subtle. Older patients may present with hypothermia or confusion.

Cellulitis, sepsis, meningitis, and UTI are the most common presentations. Patients may therefore present with the following signs depending on the focus of infection: raised erythema with clearly demarcated margins or macular erythema with indistinct borders (cellulitis); tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea, or poor capillary refill (sepsis); seizures, stiff neck, or Kernig's or Brudzinski's signs (meningitis); or suprapubic tenderness or costovertebral angle tenderness (UTI).

Less common manifestations include septic arthritis, pneumonia, conjunctivitis, sinusitis, otitis media, and intra-abdominal infection. Patients may therefore present with the following signs depending on focus of infection: hot, swollen, tender joint with joint effusion (septic arthritis); respiratory distress, cyanosis, nasal flaring, intercostal or subcostal indrawing, decreased breath sounds, auscultatory crackles, or pleural rub (pneumonia); nasal mucosal erythema (sinusitis); bulging tympanic membrane or myringitis (otitis media); or tender rigid abdomen, guarding, rebound tenderness, or decreased or absent bowel sounds (intra-abdominal infection).

Pregnant women

GBS can produce a wide range of manifestations including UTI, chorioamnionitis, sepsis, postnatal endometritis, and postnatal wound infection.

Pregnant women may therefore present with the following signs depending on the focus of infection: suprapubic tenderness or costovertebral angle tenderness (UTI); tachycardia, hypotension, tachypnoea, or poor capillary refill (sepsis); raised erythema with clearly demarcated margins or macular erythema with indistinct borders (cellulitis); uterine tenderness, foul-smelling or grossly purulent amniotic fluid, or fetal tachycardia and decreased heart rate variability (chorioamnionitis); or uterine tenderness (postnatal endometritis).

Spontaneous mid-gestation abortion and preterm labour may occur.

Laboratory tests

All patients should have a full blood count, serum urea nitrogen, serum electrolytes, serum glucose level, coagulation profile, liver function tests, and inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein) to determine baseline levels and assess for sepsis.

Regardless of the age of the patient, diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the bacterium from a normally sterile site (e.g., blood, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF], joint fluid).

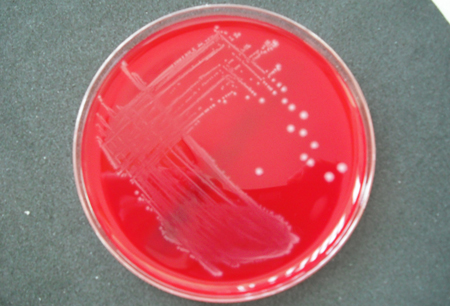

Blood cultures should be taken, with positive growth of GBS indicating sepsis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Group B streptococci on blood agarFrom the collection of Dr Brendan Healy [Citation ends].

CSF examination is required in patients with signs and symptoms of meningitis, and in all neonates with sepsis.[65] Sepsis can be indistinguishable from meningitis in neonates.[67] The CSF should routinely be sent for protein, glucose, cell count, and microscopy culture and sensitivity. A positive Gram stain in the context of a compatible clinical situation may provide a rapid presumptive diagnosis of meningitis, but growth of GBS from CSF culture confirms diagnosis of GBS meningitis. Antigen testing of CSF can be helpful, particularly if antibiotics have been given before the collection of cultures. It allows earlier identification of the causative organism, as culture results will usually take between 24 and 72 hours. All parameters should be used when interpreting the CSF results - they must be interpreted with the clinical picture.

Cultures of other sterile sites is indicated if the presentation suggests a less common focus of infection (e.g., joint aspirate in septic arthritis, bone sample in osteomyelitis, urine microscopy in UTI, sputum culture in pneumonia).[38][68] Urine culture should be performed for neonates with suspected late-onset disease.[65] If risk factors for GBS were present during labour, vaginal and placental swabs should be taken and cultured.

Interpreting culture results requires consideration of the whole clinical picture. Negative cultures do not exclude the disease, particularly if specimens are collected after giving antibiotics (e.g., neonates born to mothers who received antibiotics during labour).

The diagnostic role of polymerase chain reaction of sterile fluid for GBS is still being evaluated, but it may provide a rapid and specific diagnosis of GBS infection.[69]

Imaging studies

These have a limited role in GBS, as there are no specific radiological features. However, imaging may support the diagnosis and guide further sampling. Diagnostic imaging should not cause a delay in treatment if sepsis or meningitis is suspected.

Chest x-ray is indicated when pneumonia is suspected.

Bone and joint x-ray is indicated when septic arthritis or other bone or joint infections are suspected.[65]

Computed tomography (CT) of the head may be obtained before performing a lumbar puncture in patients with suspected bacterial meningitis, to rule out any contraindications to the procedure (e.g., elevated intracranial pressure). It is indicated in patients who are immunocompromised; have a history of central nervous system disease; have new-onset seizures; have papilloedema; or have an abnormal level of consciousness or a focal neurological deficit.[70]

Magnetic resonance imaging and CT may be useful if meningitis is diagnosed to assess for complications such as ventriculitis or brain abscess.[65]

Echocardiography is indicated when endocarditis, a complication of GBS infection, is suspected.[71]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer