Approach

The presentation of DN is variable. Up to 50% of patients may be completely asymptomatic.[1][3] Characteristic history and clinical examination findings are often sufficient to diagnose established DN. However, because there are no distinguishing features unique to DN, other possible causes of neuropathy (e.g., hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, uraemia, alcohol use disorder) must be ruled out by careful history, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Some of these conditions occur more frequently in people with diabetes and, therefore, may co-exist with DN. For instance, long-term metformin use is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.[61] Autonomic symptoms are particularly difficult to ascribe to DN because they are often vague and non-specific, with substantial overlap with symptoms seen in the general population.

Distinguishing diabetic neuropathies from other polyneuropathies

It is important to exclude other causes of peripheral neuropathy. A thorough history and physical examination are key to distinguishing DN from other conditions with similar presentations. Initial laboratory tests should include thyroid function tests, vitamin B12, immunoglobulin electrophoresis, renal function and electrolytes, full blood count (FBC), liver function, lipid profile, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

An important differential is chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). This condition is responsive to immunotherapy and may be more common in patients with diabetes. Patients with CIDP present with tingling, pain, and, most notably, distal muscle weakness. Nerve conduction studies are useful for the diagnosis of CIDP, typically demonstrating slowed conduction velocities, conduction block, and abnormal temporal dispersion. See Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.

History for diabetic peripheral neuropathy

The history may reveal the presence of risk factors strongly associated with DN, such as a long duration of diabetes (e.g., >10 years), older age (e.g., >70 years), tall stature, and poorly controlled hyperglycaemia. Intensive blood glucose control is associated with lower rates of DN compared with conventional management.[17][25] History of dyslipidaemia with elevated triglycerides and hypertension may also be present. A history of recent falls should be elicited, which may reflect gait and balance disorders.[62]

The pain associated with peripheral DN typically manifests with sensory symptoms. These begin symmetrically in the toes and slowly advance up to the calves, before involving the fingers and arms.[7]

Symptoms vary according to the class of sensory fibres involved. The most common symptoms reflect small fibre involvement and include:[7]

Pain (burning, stinging, shooting, or deep aching)

Dysaesthesias (unpleasant abnormal sensations e.g., burning, tingling, 'pins and needles')

Numbness.

Pain is often the reason why patients with DN seek medical care. Intensity varies from mild discomfort to being disabling, and may be described as:

Sticking

Lancinating

Prickling

Burning

Aching

Boring or gnawing

Excessively sensitive.

Pain is often worse at night and may disturb sleep. Involvement of larger fibres may lead patients to complain of a feeling like walking on cotton wool.

The most distal portion of the longest nerves is affected first. Early symptoms typically involve the tips of the toes and fingers. This proceeds proximally, resulting in a 'stocking-glove' pattern of pain and sensory loss. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Progressive axonal loss in diabetic peripheral neuropathyEdwards JL, et al. Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Oct;120(1):1-34; used with permission [Citation ends].

Feeling may also be lost in the feet, with or without pain or dysaesthesias. If nociceptive fibres are involved, loss of sensation predisposes to painless injuries (e.g., an object may become lodged in the shoe and erode through the skin with normal walking and weight-bearing).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plantar ulcer due to a coin in the shoe of a patient with an insensate footFrom the collection of Dr Rayaz Malik, Weill Cornell Medicine [Citation ends].

Patients presenting with painful DN should be assessed for mood and sleep disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder, obstructive sleep apnoea), as these can affect perception of pain.[63]

Weakness is another presenting symptom but is less common, usually minor, and occurs later in the disease process.

History for diabetic autonomic neuropathy

Symptomatic autonomic neuropathy is infrequent and, in general, occurs later in the course of the disease.[64][65][66]

Patients may experience exercise intolerance due to impaired cardiovascular regulation, characterised by blunted increases in heart rate, blood pressure (BP), and cardiac output during exertion.[67]

Orthostatic hypotension, defined as a fall in systolic (20 mmHg) or diastolic (10 mmHg) BP within 3 minutes of standing, occurs in people with diabetes largely as a consequence of efferent sympathetic vasomotor denervation, with reduced vasoconstriction of the splanchnic and other peripheral vascular beds. Symptoms associated with orthostatic hypotension include:

Light-headedness

Weakness

Faintness

Dizziness

Visual impairment

Syncope on standing.

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are relatively common among patients with diabetes and may reflect diabetic GI autonomic neuropathy. Some studies have described the presence of delayed gastric emptying in up to 50% of patients with longstanding diabetes, and in severe cases it is associated with significant impairments in both quality of life and glycaemic control.[68] While the delay in gastric emptying is not always clinically apparent, the range of symptoms may include:[69]

Nausea

Post-prandial vomiting

Bloating

Loss of appetite

Early satiety.

Oesophageal dysfunction partly results from vagal dysfunction and may present with symptoms such as heartburn and dysphagia for solids.

Intermittent diarrhoea is evident in 20% of patients with diabetes, particularly those with known autonomic dysfunction.[64] Profuse watery diarrhoea typically occurs at night, especially in patients with type 1 diabetes. It may alternate with constipation and is extremely difficult to treat. History should rule out other causes of diarrhoea, especially ingestion of lactose, non-absorbable hexitols, or causative drugs.[64]

People with diabetes may also experience faecal incontinence due to poor sphincter tone.

Bladder dysfunction and impaired ability to void is present in up to 50% of people with diabetes and may result in symptoms of:

Frequency

Urgency

Nocturia

Hesitancy in micturition

Weak stream

Dribbling urinary incontinence

Urine retention.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is present in 30% to 75% of men with diabetes and can be the earliest symptom of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. However, ED is seldom attributable to autonomic neuropathy alone; it typically reflects the co-existence of other risk factors, such as:

Hypertension

Hyperlipidaemia

Obesity (leading to increased aromatase activity and reduced androgens)

Psychogenic factors.

Women with diabetes may have decreased sexual desire and increased pain during intercourse, and are at risk of decreased sexual arousal and inadequate lubrication.[70]

Sudomotor dysfunction manifests as anhidrosis, heat intolerance, dry skin, or hyperhidrosis.

Hypoglycaemia unawareness may be related to autonomic neuropathy; however, a study of patients with type 1 diabetes failed to confirm this association.[71]

Other types of DN

Other presentations of DN include:

Mononeuropathies (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome [median nerve], foot drop [common peroneal nerve])

Cranial neuropathies (extremely rare)

Diabetic truncal radiculoneuropathy (pain over the lower thoracic or abdominal wall)

Diabetic amyotrophy (severe weakness, pain, and proximal thigh muscle atrophy).

Assessment of symptoms

Questionnaires have been developed to investigate orthostatic symptoms and their severity. Validated scales include the Autonomic Symptom Profile (ASP) and the Survey of Autonomic Symptoms (SAS).[72][73] The Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the severity of patient-reported gastroparesis symptoms.[74]

The effect of pain on patients' function and quality of life may be assessed using scales such as the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form - Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (BPI-DPN) and the Norfolk Quality of Life - Diabetic Neuropathy (QOL-DN).[63]

Physical exam

Neurological examination may reveal symmetrical distal sensory loss with reduced or absent ankle reflexes. Sensory loss is defined in terms of extent, distribution, and modality, and involves assessment of:

Pinprick sensation

Light touch

Vibration

Joint position.

A quick, inexpensive, and accurate bedside screening tool for evaluating high-risk patients with established DN in the clinic includes:[75][76]

Vibration sense (using a 128-Hz tuning fork)

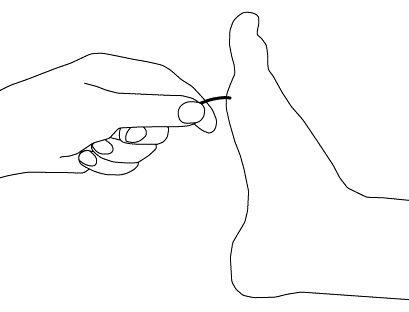

Test bilaterally on the bony prominence of the big toe’s distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint with the patient’s eyes closed. Ask the patient to report when vibration ceases. A trial should be conducted when the tuning fork is not vibrating to be certain that the patient is responding to vibration and not pressure.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Vibratory testingCreated by the BMJ Group [Citation ends].

Ankle reflexes (Achilles tendon)

Ankle reflexes should be examined using an appropriate reflex hammer (e.g., Tromner or Queen square). With the patient seated and foot relaxed and slightly dorsiflexed, tap the tendon directly. If the reflex is absent, the patient should be asked to perform the Jendrassik manoeuvre (i.e., hooking the fingers together and pulling). Reflexes that respond only with reinforcement are marked as 'present with reinforcement'; if the reflex is absent even with the Jendrassik manoeuvre, it is graded as 'absent'.

Loss of light touch sensation (using 10-g monofilament)

For this exam, it is important that the patient's foot be supported, with the sole resting on a flat, warm surface. The monofilament should initially be prestressed by applying it perpendicularly to the dorsum of the examiner’s finger several times. The filament is then applied to the plantar surface of the great toe (hallux), avoiding callused areas. The toe should not be held directly. The filament is applied perpendicularly with even pressure for <1 second. With closed eyes, patients should identify sensation correctly at least 8 out of 10 times for normal sensation; 1-7 correct responses suggest reduced sensation, and none indicates loss of sensation.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Light touch testing with monofilamentCreated by the BMJ Group [Citation ends].

Foot inspection

Examine for ulcers, calluses, and previous amputations.

Painless injuries may be apparent on examination. These often occur over pressure points on the foot and most commonly over the metatarsal heads. Infection often complicates the situation and can be followed by gangrene if vascular dysfunction is present.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Plantar ulcer in a patient with type 1 diabetesFrom the collection of Dr Rodica Pop-Busui, University of Michigan [Citation ends].

In patients with involvement of large sensory fibres, gait ataxia may develop, especially at night or when the patient walks with closed eyes. In patients with severe DN, motor deficits may emerge, presenting as weakness in toe dorsiflexion and the intrinsic muscles of the hands.

Resting tachycardia and a fixed heart rate are characteristic late findings of vagal impairment in patients with diabetes. Resting heart rates typically range from 90-100 bpm, with occasional increases up to 130 bpm.[67] Resting heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) are bedside assessments that can detect early signs of cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) , although resting tachycardia alone is not specific to CAN.

Measurement of supine and standing BP is important when evaluating for orthostatic hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension is a late and insensitive sign of CAN; it should be attributed to CAN only after other causes have been excluded. Other findings such as QT interval prolongation and reverse dipping patterns on ambulatory BP monitoring are specific but insensitive indices of CAN.[22][77]

Bladder dysfunction related to autonomic neuropathy may progress to urinary retention often accompanied by a distended bladder on abdominal examination.

Investigations

DN is often a clinical diagnosis. The criteria used for diagnosis can differ between clinical practice and research settings.[3][22] For research and clinical trials, it is recommended that the diagnosis and classification of DN be based on at least one standardised measure from each of the following categories:[3][78][79]

Clinical symptoms

Clinical examination

Basic laboratory tests

Electrophysiological testing

Quantitative sensory testing (QST)

Autonomic function testing (includes heart-rate variability testing)

Skin biopsy or non-invasive technique (e.g., corneal confocal microscopy) to assess nerve fibres.

For patients not already diagnosed with diabetes, diabetes-diagnostic testing should be performed to confirm or exclude diabetes, as diabetic neuropathy may be the first presentation. This includes fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, and a 2-hour plasma glucose level following a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Baseline tests to assess alternative causes and comorbidities include thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, full blood count (FBC), renal function tests (electrolytes, urea, creatinine, urinary microalbumin, and measurement of estimated glomerular filtration rate), lipid profile, liver function tests, immunoglobulin electrophoresis, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

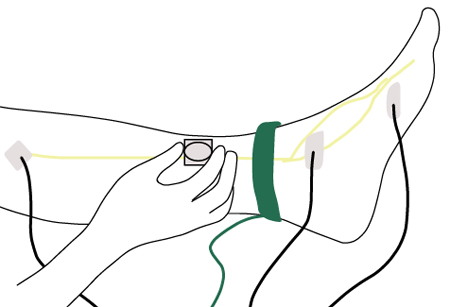

Electrophysiological testing (nerve conduction tests and electromyography [EMG]) and specialised neurological evaluation are indicated when clinical features are atypical, such as when motor deficits exceed sensory deficits, neurological deficits are markedly asymmetric, symptoms initially involve the upper extremities, or there is rapid progression.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nerve conduction testing of the lower legCreated by the BMJ Group [Citation ends].

QST quantifies vibration perception threshold (VPT) and thermal perception threshold using a variety of instruments and algorithms. Two main approaches are used: the method of limits and the method of levels. In the method of limits, the patient signals when they first detect an increasingly strong stimulus (ascending ramp) or when they no longer detect a decreasing stimulus (descending ramp). In contrast, the method of levels involves presenting stimuli at fixed intensities, with the patient indicating whether they perceive each one. The method of levels is also referred to as a forced-choice algorithm.[80] QST is particularly useful for detecting small-fibre neuropathy when other examinations are normal.[81] VPT shows high sensitivity and specificity relative to nerve conduction velocity (NCV) testing and neurological examination, and elevated VPTs in the 50-300 Hz range are associated with DN.[82] Abnormal thermal thresholds are reported in about 75% of patients with moderate-to-severe diabetic peripheral neuropathy, with elevated heat-pain thresholds in 39%.[82] Although thermal and vibration thresholds generally correlate, they may diverge in some patients, suggesting predominant involvement of either small-fibre or large-fibre systems.

Cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests (CARTs)[22][65][66][83]

A group of standardised bedside tests that primarily assess parasympathetic (vagal) and sympathetic tone.

Tests to evaluate parasympathetic function include: heart rate (HR) response to deep breathing, the Valsalva manoeuvre, and HR response to postural changes.

The HR response to deep breathing is the most commonly used test for assessing parasympathetic function, with a specificity of around 80%.

The Valsalva manoeuvre, although informative, requires greater patient cooperation and may not be feasible for all individuals. HR response during the Valsalva manoeuvre are influenced by accompanying BP changes.

Sympathetic function can be evaluated through BP responses to standing and the Valsalva manoeuvre, as well as sustained isometric muscle contraction.

Despite limited sensitivity, orthostatic BP measurement remains a standard component of CAN assessment.

CARTs are non-invasive, safe, reproducible, and correlate well with peripheral nervous system dysfunction. Because no single test is sufficiently sensitive or specific on its own, more than one HR-based and BP-based test is recommended for accurate diagnosis and monitoring of CAN.

Heart rate variability (HRV)[22][65][66][67][83][84]

Short-term resting HRV analysis complements CARTs by quantifying beat-to-beat sinus arrhythmia under standardised conditions (typically a 5-minute recording).

HRV can be assessed with time- or frequency-domain methods and broadly reflects autonomic (especially vagal) modulation.

Reduced HRV supports a diagnosis of CAN and independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Skin biopsy is a validated technique for determining intra-epidermal nerve fibre density, and may be useful in diagnosing DN, particularly small-fibre neuropathy.[79] Newer non-invasive modalities, such as corneal confocal microscopy (CCM; images the corneal sub-basal nerve plexus) and laser Doppler imaging flare technique (LDI flare; assesses the small-fibre axon reflex-mediated neurogenic vasodilatory response to cutaneous heating), have demonstrated comparable accuracy to intra-epidermal nerve fibre density assessment.[85][86] CCM has shown extremely high sensitivity and specificity for diabetic autonomic neuropathy.[87]

The following investigations are performed only if the history and physical examination raise concern for specific autonomic manifestations:

Gastric emptying studies with double-isotope scintigraphy can detect abnormalities in gastric motility and are useful in confirming a diagnosis of gastroparesis where clinical uncertainty exists.

A hydrogen breath test can diagnose bacterial overgrowth, which is often a cause of diarrhoea in patients with diabetes. Hydrogen breath tests using non-radioactive C-13 acetate or C-13 octanoic acid as a label are safe, inexpensive, and correlate well with scintigraphy results.

Barium meal studies may be useful for identifying mucosal lesions or mechanical obstruction.

Gastroduodenoscopy is recommended to exclude pyloric or other mechanical obstructions.

Two-dimensional gastric ultrasonography has been validated for assessing gastric emptying of liquids and semi-solids, while three-dimensional ultrasound offers a more comprehensive assessment of total gastric volume and motility.

Anorectal manometry is indicated for evaluating sphincter tone and the rectal-anal-inhibitory reflex. It can distinguish colonic hypomotility from rectosigmoid dysfunction in patients with obstructive defaecation symptoms.

For large-volume diarrhoea, testing for faecal fat should be conducted. If malabsorption is suspected, further evaluation may include a 72-hour faecal fat collection and/or the D-xylose test.

If there is significant steatorrhoea, pancreatic function tests should be performed.

If coeliac disease is suspected (increased risk in type 1 diabetes), serological testing for anti-tissue transglutaminase and anti-endomysial antibodies should be performed.

Patients with ED should be investigated with a morning serum total testosterone.[34][88] Further specialised testing may also be necessary. See Erectile dysfunction.

Diabetic bladder dysfunction should be evaluated by:[89]

Urinary culture

Post-void ultrasound, to assess residual volume and upper-urinary tract dilation

Cystometry and voiding cystometrogram

Video-urodynamic studies.

Further investigations mainly used in research

GI neuropathies

GI manometry should be considered as a research technique to investigate gastric and intestinal motility/emptying.

Gastric MRI has been used to measure gastric emptying and motility with excellent reproducibility, but its use is limited to research purposes.

Assessment of sudomotor innervation

Used mainly for research due to limited data.

Tests of sudomotor function evaluate the extent, distribution, and location of deficits in sympathetic cholinergic function. These tests may include:[64][65][66][90]

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART)

Sweat imprint

Thermoregulatory sweat test (TST)

Sympathetic skin response: some devices can provide a quantitative assessment of sudomotor function using direct current stimulation and reverse iontophoresis. These devices measure the ability of sweat glands to release chloride ions in response to electrochemical activation by recording local skin conductance.

Cardiac sympathetic innervation imaging

Quantitative scintigraphic assessment of sympathetic innervation of the human heart is possible using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) and positron emission tomography (PET) with C-11 meta-hydroxyephedrine.[91] However, no standardised methods or normative values exist, and the high costs and the available data on the reproducibility limit their use to research only.[65][66]

Sympathetic outflow measurement

Sympathetic outflow, at rest and in response to various physiological perturbations, can be measured directly by microelectrodes inserted into a fascicle of a distal sympathetic nerve to the skin or muscle (microneurography).

Fully automated sympathetic neurogram techniques provide a rapid and objective method that is minimally affected by signal quality and preserves beat-by-beat data.[65][66][83][92]

Cardiac vagal baroreflex sensitivity

May be used in research protocols to assess cardiac vagal and sympathetic baroreflex function.

24-hour BP monitoring

Attenuation (non-dipping) and loss of BP nocturnal fall (reverse dipping) on ambulatory BP monitoring have been associated with CAN and attributed to disruption of circadian variation in sympathovagal activity.[93]

Non-dipping and reverse dipping are independent predictors of cardiovascular events and progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Pain-related evoked potentials

Used for research only.

Nerve axon reflex/flare response

Stimulation of the nociceptive C fibre results in both orthodromic conduction to the spinal cord and antidromic conduction to other axon branches, which stimulates the release of peptides, such as substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide, which causes vasodilation and increased blood flow. This is known as the axon reflex or flare response. An impaired axon reflex indicates small-fibre neuropathy.

Used for research only. More data are needed before this test can be recommended for clinical use.[94]

Neuropad

A simple visual indicator test, which uses a colour change to define the integrity of the skin sympathetic cholinergic innervation.

Neuropad responses have been shown to correlate with the modified neuropathy disability score (NDS), QST, and intra-epidermal nerve fibre (IENF) loss with relatively high sensitivity, but lower specificity for detecting distal symmetrical polyneuropathy (DSPN).[95]

However, the studies had relatively small samples; further large-scale validation is needed.

Assessment for common comorbidities

Diabetes-related foot disease

DN is the primary cause of diabetic foot problems and ulceration, the leading causes of diabetes-related hospital admissions and non-traumatic amputation.[4]

The diagnosis of foot complications in a person with diabetes is a clinical diagnosis based on thorough history and examination.

See Diabetes-related foot disease.

Retinopathy

All patients with diabetes are regularly screened for retinopathy.

Signs of retinopathy include decreased vision and retinal findings such as dot and blot haemorrhages, microaneurysms (background retinopathy), and/or neovascularisation (proliferative retinopathy).

See Diabetic retinopathy.

Nephropathy

All patients with diabetes receive regular monitoring of renal function. Evaluation should include urea, creatinine, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), and measurement of estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Patients are often asymptomatic and may not develop symptoms until advanced stages of nephropathy. In advanced stages, initial constitutional symptoms may be non-specific (e.g., fatigue and anorexia).

Presence of other microvascular complications of diabetes (neuropathy, retinopathy) should prompt evaluation for diabetic kidney disease.

Peripheral arterial disease

Peripheral arterial disease may be missed in patients with DN, as perception of rest pain and claudication is reduced.

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) may be unreliable in patients with diabetes; other tests such as toe-brachial index may be considered for diagnosis.[96]

See Peripheral arterial disease.

Depression

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is commonly associated with comorbid mood disorders, particularly depression and anxiety.[63][97][98][99] These mood disorders can influence how patients perceive pain.

Depressive symptoms often arise due to factors such as pain intensity, the unpredictability of neuropathy symptoms, perceived lack of control over treatment, limitations in daily activities, and changes in social self-image.[97][100]

Screening with a validated tool such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 may help with identification and diagnosis.

See Depression in adults.

Sleep disorders

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer