General principles

Diagnose POTS if a patient has:[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

Frequent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance when standing that:

Interfere with daily living activities

Improve rapidly when they return to a supine position

Have continued for at least 3 months

and

An increase in heart rate by ≥30 bpm (or ≥40 bpm in patients aged 12 to 19 years old) within 10 minutes of standing from a supine position or head-up tilt (without orthostatic hypotension) that is not due to other causes of sinus tachycardia.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, identify any comorbidities commonly associated with POTS, and exclude other differentials.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Symptoms of orthostatic intolerance include:

Palpitations[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Lightheadedness[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Blurred vision[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

Exercise intolerance (which may also be a non-orthostatic feature of POTS)[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Presyncope and syncope[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Tremor[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Generalised weakness[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Fatigue (which may also be a non-orthostatic feature of POTS).[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

However, be aware that symptoms of POTS are not limited to changes in posture. Non-orthostatic symptoms include:

Dyspnoea[11]Boris JR, Bernadzikowski T. Demographics of a large paediatric postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome program. Cardiol Young. 2018 May;28(5):668-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29357955?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Reilly CC, Floyd SV, Lee K, et al. Breathlessness and dysfunctional breathing in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): The impact of a physiotherapy intervention. Auton Neurosci. 2020 Jan;223:102601.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2019.102601

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31743851?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Deb A, Morgenshtern K, Culbertson CJ, et al. A survey-based analysis of symptoms in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015 Apr;28(2):157-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2015.11929217

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25829642?tool=bestpractice.com

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal pain[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Nayagam JS. Managing gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with PoTS: a UK DGH experience. Br J Cardiol. July 2019;26:101-4.

https://bjcardio.co.uk/2019/07/managing-gastrointestinal-manifestations-in-patients-with-pots-a-uk-dgh-experience

Exercise intolerance[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Fatigue[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Headache[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Sleep disturbance[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Cognitive impairment[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Chest pain[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Bladder disturbance.[35]Faure Walker N, Gall R, Gall N, et al. The postural tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) bladder-urodynamic findings. Urology. 2021 Jul;153:107-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33676954?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Kaufman MR, Chang-Kit L, Raj SR, et al. Overactive bladder and autonomic dysfunction: lower urinary tract symptoms in females with postural tachycardia syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Mar;36(3):610-3.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/nau.22971

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26859225?tool=bestpractice.com

Determine the duration of the patient’s symptoms; for a diagnosis of POTS, symptoms should have lasted for at least 3 months.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

Ask about risk factors for POTS, which include:

Recent viral infection (present in around 50% of patients)[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Benarroch EE. Postural tachycardia syndrome: a heterogeneous and multifactorial disorder. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Dec;87(12):1214-25.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.013

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23122672?tool=bestpractice.com

Pregnancy[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Relevant associated comorbidities, such as migraine headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, asthma, fibromyalgia, and autoimmune diseases, particularly Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and coeliac disease.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Shaw BH, Stiles LE, Bourne K, et al. The face of postural tachycardia syndrome - insights from a large cross-sectional online community-based survey. J Intern Med. 2019 Oct;286(4):438-48.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/joim.12895

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30861229?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Lewis I, Pairman J, Spickett G, et al. Clinical characteristics of a novel subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Intern Med. 2013 May;273(5):501-10.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/joim.12022

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23206180?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Miller AJ, Stiles LE, Sheehan T, et al. Prevalence of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2020 Mar;224:102637.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31954224?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:89-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.006

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29519641?tool=bestpractice.com

Check for features of other conditions that may explain the patient’s symptoms. See Differentials.

Physical examination

Check the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure while they are supine and then standing.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

This is known as the 10-minute standing test.

The patient’s heart rate will typically increase by ≥30 bpm (or ≥40 bpm in patients aged 12 to 19 years old) after changing position from supine to standing, with no orthostatic hypotension (sustained drop in systolic blood pressure by ≥20 mmHg).[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017 Aug 1;136(5):e25-e59.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28280232?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Allow at least 5 minutes of a supine position and at least 1 minute of standing before checking orthostatic vital signs.[40]Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:89-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.006

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29519641?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is no significant variation in the patient’s heart rate after 1 minute of standing, repeat the standing heart rate and blood pressure check at 3, 5, and 10 minutes.[40]Roma M, Marden CL, De Wandele I, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:89-96.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.02.006

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29519641?tool=bestpractice.com

Note that changes in heart rate are often not apparent after 1 minute of standing in practice. A common mistake is to focus on the changes in heart rate after 1 minute of standing only, rather than the full 10 minutes, which can lead to misdiagnosis.

Be aware that some patients have hyperadrenergic POTS, and have increased sympathetic response and excess circulating catecholamine.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with hyperadrenergic POTS will have orthostatic hypertension (increase in systolic blood pressure ≥10 mmHg after standing for 10 minutes).[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Undertake a careful cardiac examination to rule out significant structural heart disease.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

Examine the patient for other associated comorbidities, which include:[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

If the patient has an atypical presentation, examine for neurological diseases that can sometimes be associated with POTS, such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and peripheral neuropathy, although these are uncommon.[41]Kanjwal K, Karabin B, Kanjwal Y, et al. Autonomic dysfunction presenting as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J Med Sci. 2010 Mar 11;7(2):62-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.7150/ijms.7.62

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20309394?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial investigations

Electrocardiogram

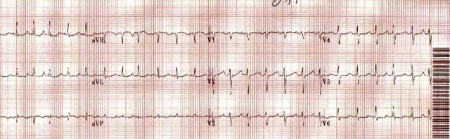

Perform a 12-lead ECG in all patients, to rule out other causes of a patient’s symptoms.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

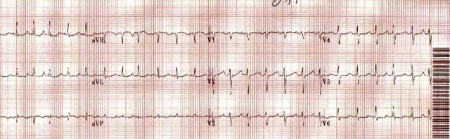

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing normal sinus rate and rhythm before the episodeCheema MA et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4):e227789; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing sinus tachycardia during tilt-table testingCheema MA et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4):e227789; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing sinus tachycardia during tilt-table testingCheema MA et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4):e227789; used with permission [Citation ends].

Blood tests

Order tests to rule out other causes of the patient’s presentation, which should include thyroid function tests, morning serum cortisol level, and full blood count.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Goodman BP. Evaluation of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:12-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29705015?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, order electrolytes to rule out causes such as adrenal insufficiency.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

In practice, electrolytes should also be checked after starting certain pharmacological treatments for POTS, such as fludrocortisone or desmopressin.

Other investigations

Holter monitor

Consider a 24-hour Holter monitor, which can help confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating the association between tachycardia and orthostatic changes.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

A Holter monitor can also rule out supraventricular arrhythmias that may have a similar presentation to POTS.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Tilt-table test

Organise a tilt-table test if:

The diagnosis is unclear after the initial assessment of orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate and you have a high suspicion of POTS.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

In this scenario, a tilt-table test is helpful because it will provide an assessment of vital signs over a greater time period compared with a simple 10-minute standing test

OR

The patient is not able to perform a 10-minute standing test.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

Echocardiogram

Organise echocardiogram to exclude heart failure as a differential if you suspect this from the history or there are signs of ventricular dysfunction found on examination (e.g., pitting oedema of the lower extremities, distended jugular veins).[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Further investigation

If the patient’s symptoms do not resolve or significantly improve, consider referral to a centre experienced with the autonomic testing of POTS, where available, to organise further investigation of the underlying pathology.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

However, further investigation should not be performed routinely because the significance for patient management and outcome is unclear.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Further investigations include:

Supine and upright plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline level[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Thermoregulatory sweat test[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Detects autonomic neuropathy which is associated with POTS.[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test[42]Goodman BP. Evaluation of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:12-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29705015?tool=bestpractice.com

Should be considered if neuropathic POTS is suspected.[42]Goodman BP. Evaluation of postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Auton Neurosci. 2018 Dec;215:12-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2018.04.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29705015?tool=bestpractice.com

Neuropathic POTS is associated with peripheral venous pooling and reduced effective intravascular volume, which is caused by peripheral sympathetic denervation.[1]Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): state of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health expert consensus meeting - part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021 Nov;235:102828.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102828

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34144933?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

Valsalva manoeuvre and deep breathing test with haemodynamic monitoring[2]Sheldon RS, Grubb BP 2nd, Olshansky B, et al. 2015 Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jun;12(6):e41-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25980576?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

Can detect autonomic dysfunction.[4]Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of chronic orthostatic intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Mar;36(3):357-72.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.12.024

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32145864?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing sinus tachycardia during tilt-table testingCheema MA et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4):e227789; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing sinus tachycardia during tilt-table testingCheema MA et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 20;12(4):e227789; used with permission [Citation ends].