RCC is often asymptomatic and commonly diagnosed after an incidental finding. More than 50% of RCCs are diagnosed incidentally; up to 40% of renal masses detected incidentally are small and localised.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[59]Luciani LG, Cestari R, Tallarigo C. Incidental renal cell carcinoma-age and stage characterization and clinical implications: study of 1092 patients (1982-1997). Urology. 2000 Jul;56(1):58-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10869624?tool=bestpractice.com

Subsequent data suggest these figures may be higher.[60]Vasudev NS, Wilson M, Stewart GD, et al. Challenges of early renal cancer detection: symptom patterns and incidental diagnosis rate in a multicentre prospective UK cohort of patients presenting with suspected renal cancer. BMJ Open. 2020 May 11;10(5):e035938.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/5/e035938.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32398335?tool=bestpractice.com

When localised malignant-appearing renal masses are detected on imaging, patients should be referred to a urologist. The urological assessment may be for active surveillance or biopsy, but most commonly for nephrectomy, which can be both therapeutic and diagnostic. Advanced disease can be referred for image-guided renal or metastatic lesion biopsy. These patients will need a referral to both a medical oncologist and a urologist (the latter for consideration of nephrectomy). Patients with known heritable syndromes may be approached with more vigilance in terms of screening, diagnosis, and follow-up.

Historical factors

Renal masses are usually only symptomatic late in the disease. The classic triad of haematuria, flank pain, and abdominal mass is uncommon (occurring in <5% of patients at presentation) and is indicative of aggressive histology locally and advanced disease.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[16]Kawaciuk I, Hyrsl L, Dusek P, et al. Influence of tumour-associated symptoms on the prognosis of patients with renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42(5):406-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18932106?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]López-Chaim AI, Holt SK, Holmberg MH, et al. Symptomatic presentation of renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol. 2025 Nov 4;43(1):668.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

Rarely, patients present with symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain or respiratory symptoms.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

Around 10% to 40% of RCCs will develop paraneoplastic syndromes, none of which are specific to RCC.[19]Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int. 2009;83(1):1-11.

https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/224860

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19641351?tool=bestpractice.com

Sequelae of these syndromes vary depending on the organ system involved, but include symptoms associated with hypercalcaemia, liver dysfunction (from metastatic disease or Stauffer's syndrome [liver failure due to paraneoplastic syndrome in the absence of liver metastases]), excess adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), anaemia, polycythaemia (mediated by inappropriate erythropoietin production), and neurological dysfunction (such as myopathy).[19]Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int. 2009;83(1):1-11.

https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/224860

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19641351?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with causative hereditary syndromes may present with dermatological, ophthalmic, or other symptoms associated with characteristic pathology in other organ sites.

Obtaining a detailed history and family history is important. Family history may be positive for renal cancer or hereditary syndromes (e.g., von Hippel-Lidau [VHL], Birt-Hogg-Dube [BHD], type 1 papillary RCC, hereditary leiomyomatous renal cell cancer syndrome).[31]Maher ER. Hereditary renal cell carcinoma syndromes: diagnosis, surveillance and management. World J Urol. 2018 Dec;36(12):1891-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6280834

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29680948?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic risk evaluation (which may include genetic counselling and germline testing) should be considered for patients with a strong family history.[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

History may reveal associated risks including obesity, hypertension, dialysis/acquired renal cystic disease, smoking (past or present), or occupational exposure to asbestos/cadmium).[28]Kabaria R, Klaassen Z, Terris MK. Renal cell carcinoma: links and risks. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016 Mar 7;9:45-52.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790506

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27022296?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Physical examination has a limited role in diagnosis but may prompt further work-up, and, in combination with certain laboratory findings, may be suggestive of RCC. A full physical examination may reveal evidence of local or distant disease sequelae.

Physical findings that may suggest renal malignancy are palpable abdominal masses (especially in thin people), cervical lymphadenopathy, lower leg oedema suggesting venous compromise, and scrotal varicocele in men.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

Hypertension, fever, cachexia, and paraneoplastic syndrome findings may be present, although they are not specific for RCC. Physical signs of paraneoplastic syndromes include pallor, cachexia, and myoneuropathy (muscle weakness associated with both primary muscle fibre pathology and associated nerve pathology). Signs of hepatic dysfunction may be present due to liver metastases, or to Stauffer's syndrome (liver failure due to paraneoplastic syndrome in the absence of liver metastases).[19]Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int. 2009;83(1):1-11.

https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/224860

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19641351?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical signs of causative hereditary syndromes include papules (BHD), skin fibromas (hereditary leiomyomatous), and retinal angiomatosis (VHL).

There are currently no guidelines to recommend targeted physical examination manoeuvres to screen for RCC, as none of the findings above are sensitive or specific, even in high-risk individuals.

Physical examination should include an assessment of performance status (measures patient mobility, ambulation, ability to perform self-care), which has implications for prognosis.

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory tests are required for the assessment of renal function (serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and urinalysis) and for completeness of metastatic evaluation.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

Lactate dehydrogenase, full blood count, and calcium are important investigations in the work-up of RCC (particularly at advanced stage), in order to assess prognosis and detect the presence of paraneoplastic syndromes.[2]Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2024 Aug;35(8):692-706.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(24)00676-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38788900?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

[62]Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Mazumdar M. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with stage IV renal cell carcinoma: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Sep 15;10(18 Pt 2):6302S-3S.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/10/18/6302S.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15448021?tool=bestpractice.com

Iron and nutritional studies should be completed if anaemia is found, to rule out reversible factors; the profile is often that of anaemia of chronic disease.

If specific paraneoplastic syndromes are suspected, targeted investigations should follow. Laboratory findings in paraneoplastic syndromes may include anaemia from chronic disease; erythrocytosis from excess erythropoietin; hypercalcaemia from parathyroid hormone-related protein/lytic bone lesions/prostaglandin production; excess ACTH from hypercortisolism; and abnormal liver function tests from hepatic dysfunction.[19]Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int. 2009;83(1):1-11.

https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/224860

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19641351?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging

Imaging is paramount to diagnosis, regardless of presentation.

Diagnosis may be suggested by ultrasound.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

However, it is not possible to assess complex cystic masses and/or solid renal masses with ultrasound alone. If lesions are detected on abdominal ultrasound performed for other indications, the next investigation should be computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis with chest CT for staging.[63]Leveridge MJ, Bostrom PJ, Koulouris G, et al. Imaging renal cell carcinoma with ultrasonography, CT and MRI. Nat Rev Urol. 2010 Jun;7(6):311-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20479778?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound can be used to detect cystic and solid renal lesions, and determine if cystic renal lesions are benign, but it is less accurate than MRI and CT, especially in detecting smaller lesions and characterising more complex renal masses.[64]Meister M, Choyke P, Anderson C, et al. Radiological evaluation, management, and surveillance of renal masses in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Clin Radiol. 2009 Jun;64(6):589-600.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19414081?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Usher-Smith J, Simmons RK, Rossi SH, et al. Current evidence on screening for renal cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2020 Nov;17(11):637-42.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7610655

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32860009?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound may also be positive for uterine fibroma in patients with hereditary leiomyomatous renal cell syndrome.

Radiological assessment of potential lesions using CT (with and without contrast) is the definitive test for initial diagnosis of renal malignancy.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

MRI is an alternative, particularly if contrast is contraindicated (due to allergy or renal dysfunction).[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

MRI provides information about adrenal invasion, and the extent of vena cava involvement by tumour or thrombus if poorly defined on CT.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

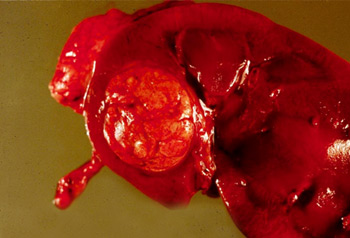

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing localised right upper pole kidney cancerFrom the collection of M. Jewett; used with permission [Citation ends].

Renal cancer most often appears as solid or complex cystic masses. CT/MRI allows for:[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

Characterisation of renal lesions

Interpretation as benign or malignant

Assessment of renal mass invasiveness, lymph node and venous involvement, and the condition of the adrenal glands and other solid organs

When renal lesions are detected incidentally on abdominal CT/MRI performed for other indications, findings may be sufficient to make the initial diagnosis. The Bosniak classification classifies cystic renal masses into five categories based on CT/MRI radiology.[13]Israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak MA. Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology. 2004 May;231(2):365-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15128983?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bosniak classificationTable created by Rodrigo R. Pessoa MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

All patients require chest imaging as part of staging and initial work-up to evaluate for pulmonary metastases. CT is preferred; chest x-ray is indicated if CT is unavilable.[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Further work-up is required if metastasis is indicated by clinical or laboratory findings.[2]Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2024 Aug;35(8):692-706.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(24)00676-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38788900?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

For example, a bone scan can be done for bone pain or elevated alkaline phosphatase. MRI brain may be indicated for localising neurological signs and symptoms, or when systemic therapy or cytoreductive nephrectomy is being considered in patients with metastases.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) tracers is not routinely recommended, but may be useful in certain circumstances, (e.g., for follow-up of advanced/metastatic disease, evaluation before metastasectomy, or in patients with certain hereditary syndromes).[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

FDG-PET has higher sensitivity and accuracy than bone scan to detect bone metastasis in RCC.[66]Wu HC, Yen RF, Shen YY, et al. Comparing whole body 18F-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and technetium-99m methylene diphosphate bone scan to detect bone metastases in patients with renal cell carcinomas - a preliminary report. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002 Sep;128(9):503-6.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12164505

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12242515?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Liu Y. The place of FDG PET/CT in renal cell carcinoma: value and limitations. Front Oncol. 2016 Sep 6;6:201.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2016.00201/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27656421?tool=bestpractice.com

FDG-PET may have a role in pre-nephrectomy staging and surveillance of patients with fumarate hydratase (FH)-deficient, succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient, and hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) tumours.[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[68]Nikolovski I, Carlo MI, Chen YB, et al. Imaging features of fumarate hydratase-deficient renal cell carcinomas: a retrospective study. Cancer Imaging. 2021 Feb 19;21(1):24.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40644-021-00392-9

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33608050?tool=bestpractice.com

Histopathology (surgical resection or biopsy)

If CT/MRI demonstrates a malignant renal mass with no evidence of distant metastatic disease, biopsy is not routinely indicated (as it is unlikely to alter management and patients are usually counselled to proceed with surgical resection and diagnosis is confirmed on surgical pathology.)[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[69]Lavallée LT, McAlpine K, Kapoor A, et al. Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada (KCRNC) consensus statement on the role of renal mass biopsy in the management of kidney cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019 Dec;13(12):377-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6892686

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31799919?tool=bestpractice.com

The role of biopsy for indeterminate localised renal masses is, however, controversial. Evidence suggests that there may be a role for surveillance of small renal masses (SRMs) <4 cm in individuals with certain tumour histologies on biopsy at diagnosis; however, biopsy is less accurate in smaller lesions.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[69]Lavallée LT, McAlpine K, Kapoor A, et al. Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada (KCRNC) consensus statement on the role of renal mass biopsy in the management of kidney cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019 Dec;13(12):377-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6892686

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31799919?tool=bestpractice.com

Typically, if metastatic disease is found on staging, biopsy of the most accessible metastatic lesion is performed to make the diagnosis. However, if nephrectomy is still being considered, surgical pathology is sufficient. Finally, biopsy of a renal mass may also be required to confirm renal metastases from another primary malignancy for staging purposes or if another diagnosis (e.g., abscess), is suspected.[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[69]Lavallée LT, McAlpine K, Kapoor A, et al. Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada (KCRNC) consensus statement on the role of renal mass biopsy in the management of kidney cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2019 Dec;13(12):377-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6892686

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31799919?tool=bestpractice.com

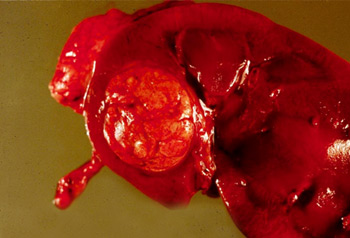

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gross pathology showing localised right upper pole kidney cancerFrom the collection of M. Jewett; used with permission [Citation ends].

Genetic risk evaluation

Genetic risk assessment (which may include germline testing and genetic counselling) should be considered for patients with RCC meeting any of the following criteria:[1]American Urological Association. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: evaluation, management, and follow up. 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/renal-mass-and-localized-renal-cancer-evaluation-management-and-follow-up

[5]Richard PO, Violette PD, Bhindi B, et al. Canadian Urological Association guideline: management of small renal masses - full-text. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022 Feb;16(2):E61-75.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8932428

[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma

[61]National Cancer Comprehensive Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Age ≤46 years

Bilateral or multifocal tumours

Family history (close blood relative with a known/likely pathogenic variant or first- or second-degree relative with RCC)

Personal or family history of mesothelioma or uveal melanoma

Specific histological characteristics that suggest a hereditary form of RCC (e.g., multifocal papillary histology; hereditary leiomyomatosis-associated RCC, RCC with fumarate hydratase deficiency or other associated histological features; multiple chromophobe, oncocytoma or oncocytic hybrid; angiomyolipomas of the kidney and one additional tuberous sclerosis complex criterion; succinate dehydrogenase-deficient RCC histology).

Patients meeting these criteria are at a significantly greater risk of having hereditary cancer. Referral to a cancer geneticist, comprehensive clinical care centre, or hospital with expertise in hereditary cancer syndromes is warranted.[18]European Association of Urology. Renal cell carcinoma. 2025 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guideline/renal-cell-carcinoma