Aetiology

Your Organisational Guidance

ebpracticenet urges you to prioritise the following organisational guidance:

Klinische richtlijn rond lage rugpijn en radiculaire pijnPublished by: KCELast published: 2018Guide de pratique clinique pour les douleurs lombaires et radiculairesPublished by: KCELast published: 2018Discogenic back pain is associated with the presence of radiologically-confirmed degenerative disc disease. Multiple studies have identified a complex mechanical and inflammatory process as the main cause of chronic discogenic pain.[15][16][17][18]

Genetic influences have been found to be more important than the mechanical effects of sporting endeavours, sitting habits, or occupational factors in the development of disc degeneration, although occupation-related postures and stresses due to the abnormal loading and lifting mechanics do also seem to be related.[19][20] Degenerative disc disease is also associated with increasing age, smoking, the presence of facet joint tropism and arthritis, abnormal pelvic morphology, and changes in sagittal alignment.

Radicular leg pain associated with degenerative disc disease results from nerve root compression due to hypertrophied facet joints, disc prolapse, or foraminal narrowing due to loss of disc height or due to instability at that motion segment.

In many cases, more than one cause of pain is responsible for the patient's symptoms. Therefore, discogenic back pain remains primarily a diagnosis of exclusion.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI spine: degenerate facet joints and a large facet cyst from the left L5S1 facet joint compressing the left S1 nerve rootFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI spine: degenerate L4-5 disc with a disc bulge and L5S1 disc with a high-intensity zoneFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

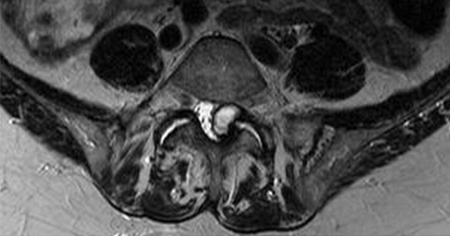

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MRI spine: degenerate L4-5 disc with a disc bulge and L5S1 disc with a high-intensity zoneFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: T2-weighted MRI spine: sagittal view (left) demonstrates degenerate discs; axial view (right) demonstrates left-sided L5S1 foraminal narrowingFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: T2-weighted MRI spine: sagittal view (left) demonstrates degenerate discs; axial view (right) demonstrates left-sided L5S1 foraminal narrowingFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

Pathophysiology

The healthy disc has a very robust structure. It is made up of a distortable, incompressible semi-fluid gel, known as the nucleus pulposus, that is surrounded by a well organised annulus fibrosus. The annulus fibrosus provides resistance to multi-directional forces and accounts for the stability of the disc. In health, the disc is the largest avascular structure in the body. At the cellular level it comprises chondrocytes, proteoglycans, extracellular matrix, and water. The normal human circadian rhythm allows for fluid shifts in and out of the disc.

Degenerative changes follow a loss of hydration of the nucleus pulposus and lead to a cascade of events at a cellular level.[21] This includes alteration of the type and nature of the proteoglycans, a loss of chondrocytes, apoptosis, and the presence of chondron clusters.[22][23][24] Disc degeneration results in inappropriate stress concentrations during loading, formation of circumferential or radial tears within the annulus fibrosus, release of inflammatory agents, and sensitisation of the pain nociceptors that are located inside the annulus.[15][16][17][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35] The outline of the disc may remain intact while the internal aspect undergoes multiple inflammatory and degenerative changes.

Progression of disc degeneration may lead to additional painful manifestations, including loss of disc height and facet joint arthrosis, disc herniation and nerve root irritation, and hypertrophic changes resulting in spinal stenosis.[1][2] As a result, patients with degenerative disc disease may present with a variety of symptoms that range from mild localised tenderness to severe excruciating radicular pain and lower extremity symptoms.

Classification

Kirkaldy Willis degenerative cascade[3]

Degenerative disc disease is divided into 3 stages:

Stage 1: temporary segmental dysfunction

Stage 2: segmental instability - characterised by disc collapse and ligamentous laxity

Stage 3: restabilisation - advanced degenerative changes (osteophytes or bone bridges between the vertebrae, disc collapse, ligamentous contractions, and joint fusion) resulting in motion restriction and stiffness in the vertebral segments.

The transition period between these stages is approximately 20 to 30 years, ultimately resulting in a stiff spine with collapsed discs.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer