History

A phaeochromocytoma should be suspected in any patient who presents with the classic triad of symptoms:[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Palpitations

Headaches

Diaphoresis

Episodic spells of the symptoms are characteristic and they can vary in duration from seconds to hours and typically get worse with time as the tumour enlarges.

Other suggestive features:

Enquiring about the family history is vital. Approximately 35% to 40% of patients with phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma (together known as PPGL) have a germline mutation in one of the known PPGL susceptibility genes such as RET (associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2) or VHL (associated with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome).[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Fishbein L, Merrill S, Fraker DL, et al. Inherited mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: why all patients should be offered genetic testing. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 May;20(5):1444-50.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4291281

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23512077?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Liu P, Li M, Guan X, et al. Clinical syndromes and genetic screening strategies of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2018 Dec 27;5(4):14-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30613466?tool=bestpractice.com

Germline mutations in the SDH subunit B, C, and D genes, or a personal history of a phaeochromocytoma, increase risk.[34]Amar L, Pacak K, Steichen O, et al. International consensus on initial screening and follow-up of asymptomatic SDHx mutation carriers. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021 Jul;17(7):435-44.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-021-00492-3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34021277?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Andrews KA, Ascher DB, Pires DEV, et al. Tumour risks and genotype-phenotype correlations associated with germline variants in succinate dehydrogenase subunit genes SDHB, SDHC and SDHD. J Med Genet. 2018 Jun;55(6):384-94.

https://jmg.bmj.com/content/55/6/384

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29386252?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical presentation of phaeochromocytoma can vary widely and 10% to 15% of cases can be completely asymptomatic with the tumour discovered incidentally during abdominal investigation for other reasons.[42]Rogowski-Lehmann N, Geroula A, Prejbisz A, et al. Missed clinical clues in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma discovered by imaging. Endocr Connect. 2018 Sep 1;7(11):1168-77.

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EC-18-0318

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30352425?tool=bestpractice.com

Approximately 3% to 7% of incidentally discovered adrenal masses are diagnosed as phaeochromocytoma.[42]Rogowski-Lehmann N, Geroula A, Prejbisz A, et al. Missed clinical clues in patients with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma discovered by imaging. Endocr Connect. 2018 Sep 1;7(11):1168-77.

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EC-18-0318

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30352425?tool=bestpractice.com

It is recommended that all patients with such masses should undergo biochemical evaluation.[43]Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016 Aug;175(2):G1-G34.

https://www.doi.org/10.1530/EJE-16-0467

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27390021?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Duh QY, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2009 Jul-Aug;15(5):450-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19632968?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination findings

Hypertension is the principal sign on examination.[45]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients often present with accelerated hypertension or hypertension refractory to multiple drug regimens. In about 48% of cases the hypertension is paroxysmal or labile in nature.[45]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

Phaeochromocytomas may present with life-threatening acute hypertensive emergencies (e.g., encephalopathy), as well as clinical consequences of long-lasting hypertension (e.g., hypertensive retinopathy, proteinuria, cardiomyopathies, or arrhythmias).[45]Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):295-311.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21565668?tool=bestpractice.com

A hypertensive crisis can be triggered by drugs, intravenous contrast, surgery, or even exercise.

Postural hypotension may be a feature due to volume contraction. Other signs associated with phaeochromocytomas include abdominal masses, tachycardia, pallor, or tremors.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory evaluation

All patients with palpitations, headaches, and diaphoresis should be investigated, whether or not they have hypertension.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Investigations should be carried out in any patient with hereditary risk that predisposes to phaeochromocytoma development, such as MEN2.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Biochemical tests

Measurement of plasma free metanephrines (also known as metadrenalines), or 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrines (also known as normetadrenaline), is recommended in patients with suspected phaeochromocytoma.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Elevations 3 times above the upper limit of normal are diagnostic.[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Blood sampling should be performed in the supine position.[47]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Some drugs may interfere with testing results (e.g., buspirone, cocaine, labetalol, levodopa, methyldopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs], paracetamol, phenoxybenzamine, sotalol, sulfasalazine, sympathomimetics, tricyclic antidepressants); review patient drug history accordingly.[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Note that urine or plasma catecholamines are no longer routinely recommended for the evaluation of phaeochromocytoma.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

A clonidine suppression test can be used to discriminate patients with mildly elevated test results for plasma normetanephrine (attributable to increased sympathetic activity) from those with elevated test results due to a phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma.[47]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Remde H, Pamporaki C, Quinkler M, et al. Improved diagnostic accuracy of clonidine suppression testing using an age-related cutoff for plasma normetanephrine. Hypertension. 2022 Jun;79(6):1257-64.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19019

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35378989?tool=bestpractice.com

Chromogranin A (an acidic monomeric protein that is stored with and secreted with catecholamine) may be elevated in patients with a neuroendocrine tumour. Chromogranin A plus urinary fractionated metanephrines has been suggested as a follow-up test for elevations of plasma metanephrines.[49]Algeciras-Schimnich A, Preissner CM, Young WF Jr, et al. Plasma chromogranin A or urine fractionated metanephrines follow-up testing improves the diagnostic accuracy of plasma fractionated metanephrines for pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jan;93(1):91-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2729153

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17940110?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging studies

Localisation studies should only be undertaken after a biochemical abnormality is demonstrated.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging is preferred.[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an option for patients in whom radiation exposure should be limited or is contraindicated (e.g., children, pregnant or lactating women).[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

MRI may be considered in patients with suspected metastatic PPGL; it can detect blood vessel invasion and liver metastases with greater sensitivity than CT.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Anatomical imaging should be complemented by functional imaging unless risk of tumour metastases or multifocal disease is low (i.e., those without previous PPGL and hereditary syndrome, with an adrenergic biochemical phenotype and a single small adrenal phaeochromocytoma [<5 cm]).[50]Timmers HJLM, Taïeb D, Pacak K, et al. Imaging of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Rev. 2024 May 7;45(3):414-34.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11074798

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38206185?tool=bestpractice.com

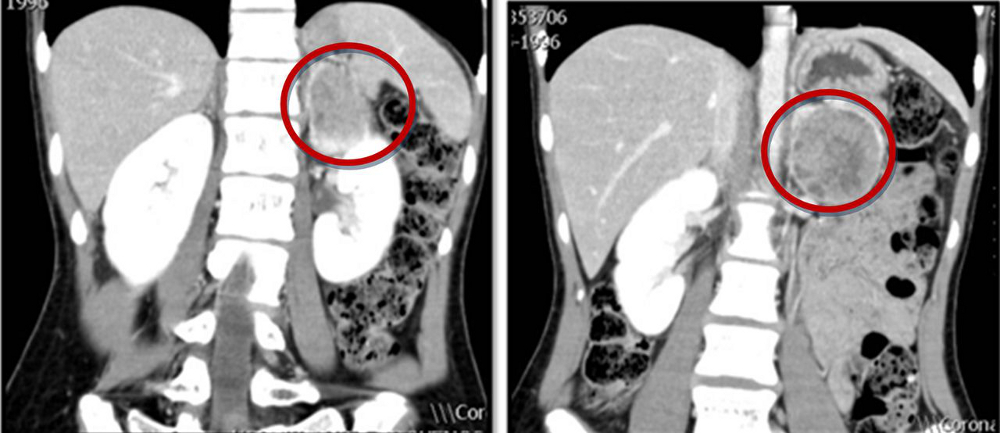

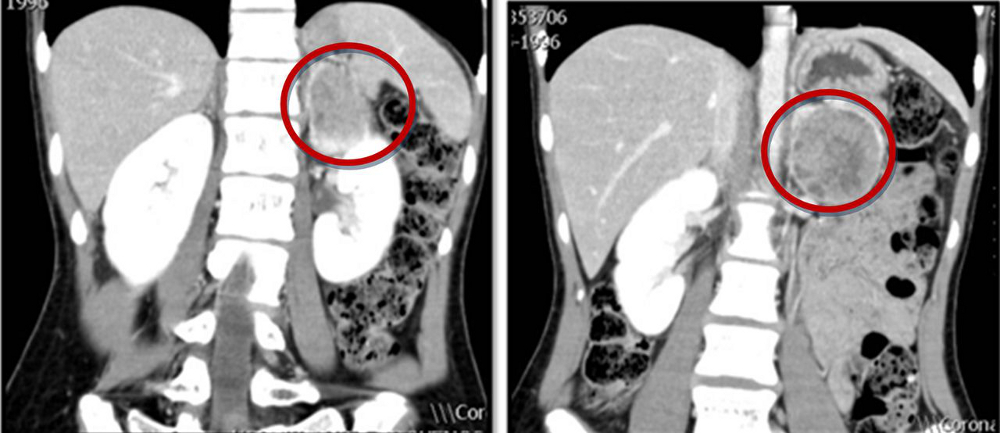

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Abdominal CT scan with mass in the left adrenal gland, compatible with a phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

Functional imaging

Functional imaging can improve detection when anatomical localisation is inconclusive, identify additional lesions in the setting of hereditary disease, and evaluate for metastatic disease.[51]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: adrenal mass evaluation. 2021 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69366/Narrative

The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society recommends somatostatin receptor-targeted (SSTR) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT as first-line functional imaging when metastatic PPGL is suspected.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT, and SSTR PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTATATE tracer (also known as PET/CT Ga-68 DOTATATEe scan), are more sensitive than I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy in the setting of metastatic and multifocal phaeochromocytoma.[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

SSTR PET/CT with 68Ga DOTATATE is highly sensitive, and often the preferred imaging modality for the detection and localisation of phaeochromocytoma in patients with SDHB-associated metastatic disease.[52]Janssen I, Blanchet EM, Adams K, et al. Superiority of [68Ga]-DOTATATE PET/CT to other functional imaging modalities in the localization of SDHB-associated metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Sep 1;21(17):3888-95.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4558308

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25873086?tool=bestpractice.com

An I-123 MIBG scan is required if treatment with I-131 MIBG is being considered (e.g., patients with inoperable PPGL).[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[50]Timmers HJLM, Taïeb D, Pacak K, et al. Imaging of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Rev. 2024 May 7;45(3):414-34.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11074798

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38206185?tool=bestpractice.com

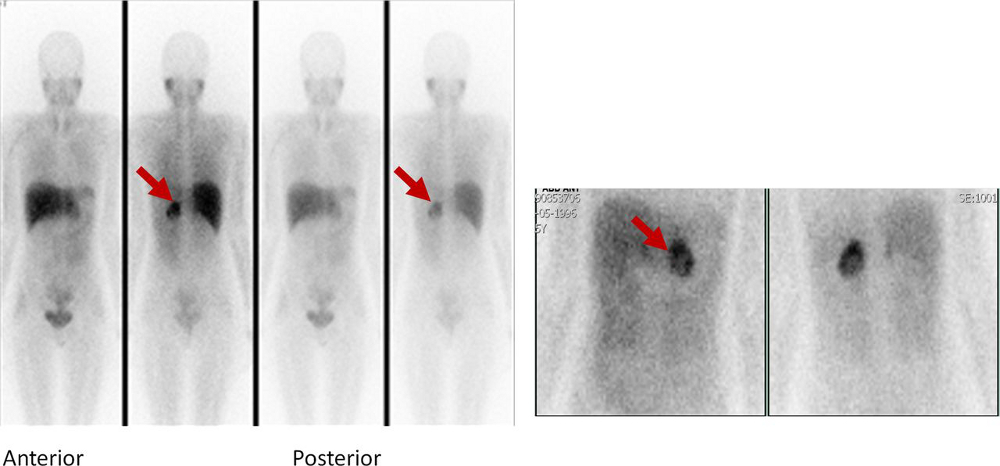

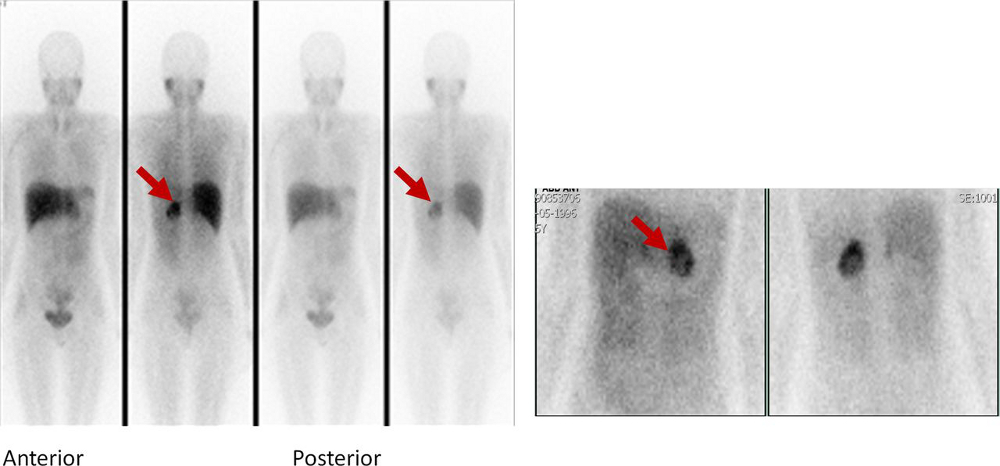

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy identified hyperfixation in the left adrenal gland compatible with phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].

Genetic testing

All patients with phaeochromocytomas should undergo genetic testing to identify potential hereditary tumour disorders that would necessitate more detailed evaluation and follow-up.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[47]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Plouin PF, Amar L, Dekkers OM, et al; Guideline Working Group. European Society of Endocrinology clinical practice guideline for long-term follow-up of patients operated on for a phaeochromocytoma or a paraganglioma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016 May;174(5):G1-10.

https://academic.oup.com/ejendo/article/174/5/G1/6655102

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27048283?tool=bestpractice.com

Patient engagement in a shared decision-making process is essential.[46]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Genetic testing may be guided by features such as:[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Positive family history (premised upon pedigree or identification of a PPGL-susceptibility gene mutation)

Syndromic features

Multifocal, bilateral, or metastatic disease

Targeted germline mutation testing (e.g., multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 [MEN2], Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome [VHL], and neurofibromatosis type 1 [NF1]) is recommended in patients with positive family history or syndromic presentation.[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with metastatic disease should undergo testing for SDHB mutations.