The goal of treatment is to eliminate the dangerous effects of excessive catecholamine production by the tumour. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment.

Hypertensive crisis

A hypertensive crisis (systolic blood pressure [BP] >250 mmHg) may occur on presentation of a phaeochromocytoma or during surgical resection of the tumour if the patient has not received adequate preoperative medical therapy.

Treatment includes immediate alpha blockade with an alpha-1 blocker (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin, or prazosin) or with the non-selective alpha-blocker, phenoxybenzamine. Intravenous agents (nitroprusside, phentolamine, or nicardipine) are short-acting and titratable, and can be used first line.[63]Nazari MA, Hasan R, Haigney M, et al. Catecholamine-induced hypertensive crises: current insights and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023 Dec;11(12):942-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37944546?tool=bestpractice.com

Nitroprusside, phentolamine, or nicardipine can be added, as required, to an oral alpha-1 blocker prescribed in the initial management of hypertensive crisis.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Clinical presentation will inform prescribing decisions. Consult a specialist when deciding on the most appropriate regimen.

Pre-treatment alpha blockade

The first step in medical management is to block the effects of catecholamine excess by controlling hypertension and expanding intravascular volume.[1]Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-65.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31390501?tool=bestpractice.com

This is achieved by first establishing adequate alpha blockade.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Alpha-1 blockers (e.g., terazosin, doxazosin, or prazosin), or the non-selective alpha-blocker phenoxybenzamine, are recommended for initial pre-treatment blockade.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

These drugs lower BP by decreasing peripheral vascular resistance.[64]Nicholson JP Jr, Vaughn ED Jr, Pickering TG, et al. Pheochromocytoma and prazosin. Ann Int Med. 1983 Oct;99(4):477-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6625381?tool=bestpractice.com

Alpha-1 blockers have a shorter duration of action than phenoxybenzamine, making them particularly useful in the perioperative period. The dose of alpha-1 blocker can be rapidly titrated, avoiding postoperative hypotension. These drugs do not enhance the release of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and therefore do not cause a reflex tachycardia.

Hydration and a high-salt diet (>5 g/day) are given for 7-14 days (or until the patient is stable) to offset the effects of catecholamine-induced volume contraction associated with alpha blockade.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Consider adding a calcium-channel blocker or metirosine

Dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers can supplement alpha blockade if additional blood pressure control is required.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers is not recommended, but may be an option if the patient is unable to tolerate alpha blockade.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Nifedipine and amlodipine are commonly recommended dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in the setting of perioperative phaeochromocytoma BP control.

Metirosine can be used in conjunction with alpha blockade to stabilise blood pressure.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Metirosine, an inhibitor of tyrosine hydroxylase, inhibits catecholamine synthesis. In patients with phaeochromocytomas, metirosine can reduce the biosynthesis of catecholamines by 35% to 80%.[65]National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem: metyrosine. Apr 2025 [internet publication].

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Metyrosine

This is particularly useful in patients with very high circulating levels of catecholamines, which can be cytotoxic to myocardial cells.

Metirosine also has a role in patients where tumour manipulation or destruction will be marked, such as patients with metastatic disease receiving chemotherapy.[66]Tada K, Okuda T, Yamashita K. Three cases of malignant pheochromocytoma treated with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and dacarbazine combination chemotherapty and alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine to control hypercatecholaminemia. Horm Res. 1998;49(6):295-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9623522?tool=bestpractice.com

It should be started 2 weeks prior to surgery. It can also be used when surgery is contraindicated.

Beta blockade after alpha blockade

Following adequate alpha blockade, which may take 3-4 days of therapy, beta blockade can be added to manage tachycardia.[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[67]Patel D, Phay JE, Yen TWF, et al. Update on pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma from the SSO Endocrine and Head and Neck Disease Site Working Group, part 2 of 2: perioperative management and outcomes of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 May;27(5):1338-47.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8638680

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32112213?tool=bestpractice.com

If beta blockade alone is used, this can precipitate a hypertensive crisis due to unopposed alpha-adrenergic stimulation.[3]Martucci VL, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr Probl Cancer. 2014 Jan-Feb;38(1):7-41.

https://www.cpcancer.com/article/S0147-0272(14)00002-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24636754?tool=bestpractice.com

Combined alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockade is often used to control BP and prevent hypertensive crisis.

Resectable phaeochromocytoma

Surgical excision of the entire adrenal gland remains the mainstay of treatment for benign and malignant phaeochromocytoma.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

If appropriate, minimally invasive resection of the tumour is preferred.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

The American Association of Endocrine Surgeons (AAES) recommends laparoscopic transabdominal or posterior retroperitoneal adrenalectomy.[68]Yip L, Duh QY, Wachtel H, et al. American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines for adrenalectomy: executive summary. JAMA Surg. 2022 Oct 1;157(10):870-7.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9386598

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35976622?tool=bestpractice.com

The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) recommends open resection if there is evidence of local invasion, malignancy, or recurrence.[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Minimally invasive adrenalectomy appears to be safe in patients with malignant phaeochromocytoma tumour size <6 cm.[69]Hue JJ, Alvarado C, Bachman K, et al. Outcomes of malignant pheochromocytoma based on operative approach: a National Cancer Database analysis. Surgery. 2021 Oct;170(4):1093-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958205?tool=bestpractice.com

Cortical-sparing adrenalectomy should be considered in patients with bilateral phaeochromocytoma (recommended by the AAES and NANETS) and familial phaeochromocytoma (recommended by NANETS).[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Yip L, Duh QY, Wachtel H, et al. American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines for adrenalectomy: executive summary. JAMA Surg. 2022 Oct 1;157(10):870-7.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9386598

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35976622?tool=bestpractice.com

This method can avoid the need for lifelong corticosteroid therapy; however, patients need to be monitored postoperatively for local recurrence.[68]Yip L, Duh QY, Wachtel H, et al. American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines for adrenalectomy: executive summary. JAMA Surg. 2022 Oct 1;157(10):870-7.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9386598

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35976622?tool=bestpractice.com

Paragangliomas are extra-adrenal tumours. They require specialised surgical approaches depending on the various locations of origin.[70]Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009 Dec;96(12):1381-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.6821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918850?tool=bestpractice.com

Unresectable disease

Patients with unresectable tumours have malignant disease with extensive local or metastatic spread that can not be removed by surgery, or have a benign tumour and are not surgical candidates for other medical reasons (e.g., a patient who is a high surgical risk because of heart failure).

Malignant or metastatic phaeochromocytomas represent approximately 10% of all catecholamine-secreting tumours. The diagnosis is based on local invasion of surrounding tissues or distant metastases.

Following initial alpha blockade, cytoreductive resection is generally the primary therapy where possible.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

NANETS recommends open resection if there is evidence of local invasion, malignancy, or recurrence.[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Locally unresectable catecholamine-secreting disease

Continued alpha blockade, with calcium-channel blockers or beta blockade if needed, facilitates BP control in patients with unresectable secreting tumours.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjustments to the BP treatment regimen may be required should additional therapy be prescribed.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Additional treatment options for patients with locally unresectable disease include radiotherapy with or without cytoreductive resection, or systemic chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide plus vincristine plus dacarbazine [CVD], or temozolomide).[28]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Jimenez C, Xu G, Varghese J, et al. New directions in treatment of metastatic or advanced pheochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas: an American, contemporary, pragmatic approach. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022 Jan;24(1):89-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35061191?tool=bestpractice.com

Temozolomide, an alkylating drug and an alternative to dacarbazine, can be used as monotherapy or in combination with other antineoplastic drugs in patients with malignant phaeochromocytomas and SDHB mutations.[72]Tena I, Gupta G, Tajahuerce M, et al. Successful second-line metronomic temozolomide in metastatic paraganglioma: case reports and review of the literature. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2018 Apr 9:12:1179554918763367.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5922490

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29720885?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Tong A, Li M, Cui Y, et al. Temozolomide is a potential therapeutic tool for patients with metastatic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma-case report and review of the literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020 Feb 18:11:61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7040234

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32132978?tool=bestpractice.com

The radiopharmaceutical iobenguane I-131 (also known as I-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine [MIBG]) may be considered if I-123 MIBG scintigraphy was positive.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) provides local tumour control and relief of symptoms at both soft tissue sites of metastases, and painful bone metastases.[74]Breen W, Bancos I, Young WF Jr, et al. External beam radiation therapy for advanced/unresectable malignant paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017 Nov 22;3(1):25-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2017.11.002

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29556576?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Fishbein L, Bonner L, Torigian DA, et al. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for patients with malignant pheochromocytoma and non-head and -neck paraganglioma: combination with 131I-MIBG. Horm Metab Res. 2012 May;44(5):405-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22566196?tool=bestpractice.com

Potential enrolment in a clinical trial should be discussed with the patient.

Somatostatin analogues (octreotide, lanreotide) or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy ([PRRT] with lutetium Lu 177 dotatate) can be considered for patients with somatostatin receptor positive disease.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, demonstrated anti-tumour efficacy in a phase 2 randomised, placebo-controlled trial that included patients with metastatic phaeochromocytoma.[76]Baudin E, Goichot B, Berruti A, et al. Sunitinib for metastatic progressive phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas: results from FIRSTMAPPP, an academic, multicentre, international, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2024 Mar 16;403(10431):1061-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38402886?tool=bestpractice.com

Catecholamine-secreting distant metastases

Continued alpha blockade, with calcium-channel blockers or beta blockade if needed, facilitates BP control in patients with unresectable secreting tumours.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjustments to the BP treatment regimen may be required should additional therapy be prescribed.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

For distant catecholamine-secreting metastases, treatment options are typically the same as those for patients with locally unresectable catecholamine-secreting disease.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Palliative EBRT may be considered for oligometastatic disease or limited metastases of the liver.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Radiofrequency ablation of hepatic and bone metastases may also be effective.[49]Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al; North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May;42(4):557-77.

https://journals.lww.com/pancreasjournal/fulltext/2013/05000/Consensus_Guidelines_for_the_Management_and.2.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591432?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Pacak K, Fojo T, Goldstein DS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation: a novel approach for treatment of metastatic pheochromocytoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Apr 18;93(8):648-9.

https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/93/8/648/2906558

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11309443?tool=bestpractice.com

Surveillance

May be appropriate for patients with locally unresectable disease or distant metastases who are asymptomatic, or have a slow-growing or low-volume tumour.[28]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

In patients with locally unresectable disease or distant metastases, surveillance includes BP and plasma free or 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrines (also known as metadrenalines) and normetanephrines (also known as normetadrenaline) every 3-12 months, depending on symptoms.[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

The need for imaging should be considered, with the modality depending on characteristics of the disease and whether radionucleotide therapy is being considered.[28]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

For patients with metastatic disease, NANETS recommends imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 3-6 months in the first year, or in patients receiving systemic therapies, and imaging with CT or MRI every 6-12 months after the first year if disease is stable.[28]Fishbein L, Del Rivero J, Else T, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and management of metastatic and/or unresectable pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):469-93.

https://nanets.net/images/2021/2021_NANETS_Consensus_Guidelines_for_Surveillance_and_Management_of_Metastatic_and_or_Unresectable_Pheochromocytoma_and_Paraganglioma.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33939658?tool=bestpractice.com

Patient with hereditary phaeochromocytoma

There is evidence in favour of cortical-sparing adrenalectomy in patients with hereditary phaeochromocytomas.[70]Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, et al. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009 Dec;96(12):1381-92.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bjs.6821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19918850?tool=bestpractice.com

This method can avoid the need for lifelong corticosteroid therapy. However, patients need to be monitored postoperatively for local recurrence.[78]Yip L, Lee JE, Shapiro SE. Surgical management of hereditary pheochromocytoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Apr;198(4):525-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15051000?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical risk

The patients at highest risk for complications include those with severe preoperative hypertension or high catecholamine-secreting tumours, and those undergoing repeat surgical interventions.[79]Plouin PF, Duclos JM, Soppelsa F, et al. Factors associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality in patients with pheochromocytoma: analysis of 165 operations at a single center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Apr;86(4):1480-6.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/86/4/1480/2848250

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11297571?tool=bestpractice.com

Removal is a high-risk surgical procedure requiring a skilled surgeon and anaesthetic team. Complete excision is vital to prevent spread of the tumour and prevent other harmful effects of hyper-catecholaminaemia. Surgical complication rates are low; mortality rates of about 2% to 3%, and morbidity rates of approximately 20%, have been reported.[80]Kinney MA, Narr BJ, Warner MA. Perioperative management of pheochromocytoma. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002 Jun;16(3):359-69.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12073213?tool=bestpractice.com

Much of the risk associated with surgery is attributable to potentially massive uncontrolled release of catecholamines subsequent to tumour manipulation during resection. Complications are less likely with medical optimisation and the current practice of strict perioperative BP control and plasma volume expansion.

Postoperatively, the sudden decrease in catecholamine levels can lead to hypotension and hypoglycaemia. Hypoglycaemia may occur secondary to loss of the catecholamine-suppressed insulin secretion postoperatively. Treatment involves intravenous glucose replacement.[81]Akiba M, Kodama T, Ito Y, et al. Hypoglycemia induced by excessive rebound secretion of insulin after removal of pheochromocytoma. World J Surg. 1990 May-Jun;14(3):317-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2195784?tool=bestpractice.com

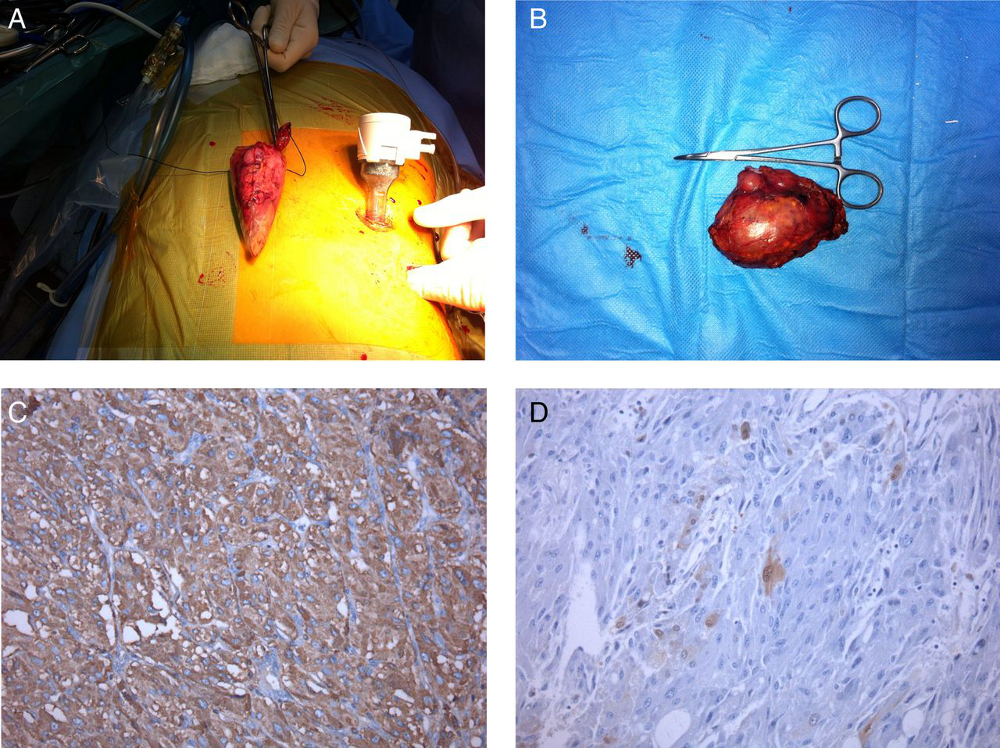

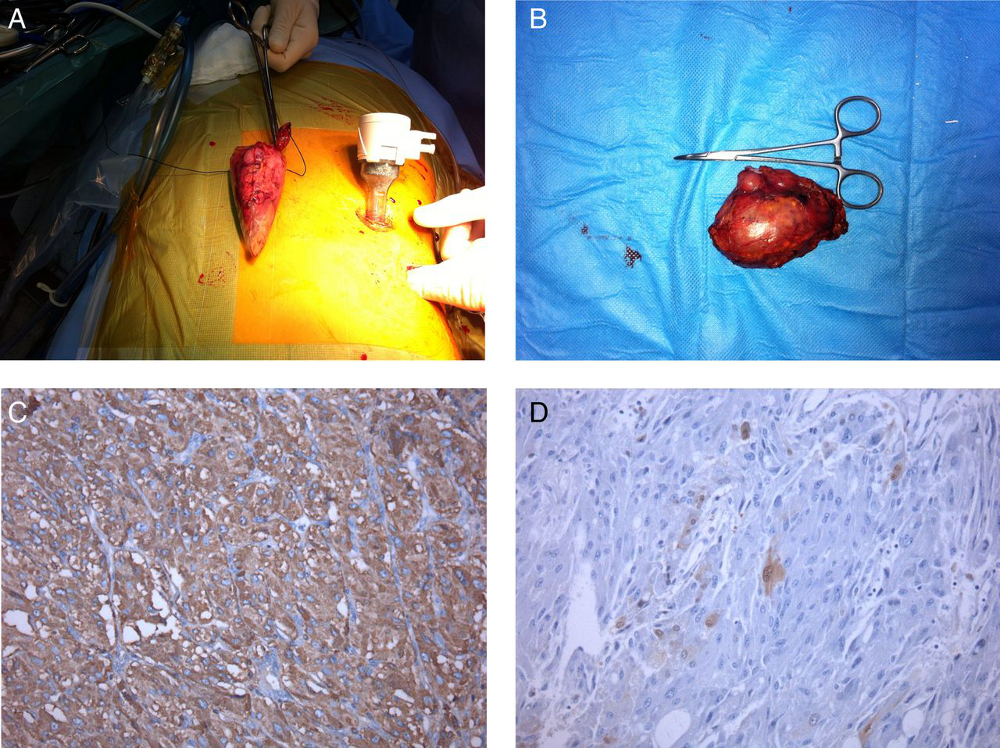

After the phaeochromocytoma is removed, catecholamine secretion usually returns to normal within 1 week. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left laparoscopic adrenalectomy: (A) macroscopic examination, 6 cm tumour; (B) microscopic examination: neoplasm of the adrenal medulla with eosinophilic cytoplasm of large cells with positive fine granular chromogranin A; (C) round and oval nucleus and sustentacular cells S100+; (D) phaeochromocytomaAlface MM et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Aug 4;2015:bcr2015211184; used with permission [Citation ends].