Approach

All patients who present with respiratory symptoms should have a work and environmental history recorded. Because many pulmonary toxins have an effect years after exposure has ended, a lifetime exposure history should be obtained. This is particularly true for patients with interstitial disease or COPD. Characteristic x-ray changes in conjunction with a work history are commonly sufficient to make the diagnosis. Bronchoscopy with biopsy and lavage is performed when confirming beryllium-related disease, or when the presentation is unusual. Pulmonary function tests are useful to determine severity and pharmacological treatment.

History

The initial step in diagnosing silicosis, coal workers' pneumoconiosis, or chronic beryllium disease is to obtain a history of exposure to silica, coal, or beryllium. For silica or coal, that exposure has typically occurred 20 or more years prior to presentation. Acute silicosis is rare, but can occur within weeks to months of extremely high exposure. Accelerated silicosis looks the same clinically as chronic silicosis, but occurs with <10 years of heavy exposure. There is no acute presentation of coal workers' pneumoconiosis. Heavy exposure to beryllium salts can cause an acute pneumonitis (acute berylliosis), which can progress to chronic beryllium disease, but the acute presentation should not occur under current well-controlled working conditions.

A lifetime occupational history should be obtained that includes all previous and current jobs. History of exposure will usually be identified because of the type of work that the patient has done. The following are examples of occupations where there may be exposure to silica, coal, or beryllium.

Silica: mining, construction, or work in a foundry.

Coal: underground coal mining.

Beryllium: ore processing, working with high-temperature ceramics, or nuclear weapons manufacturing.

It is important to ask about smoking history. Cigarette smoking is associated with an increased risk of silicosis and coal workers' pneumoconiosis.[25][26]

The presence of glutamic acid at position 69 of the B1 chain of the HLA-DP molecule is the polymorphism with the largest risk for beryllium sensitisation and disease.[18][21] Whether this polymorphism is present or not may not be known when the patient first presents. This polymorphism can be measured to determine who is at increased risk of beryllium sensitisation and/or development of chronic beryllium disease. However, it is of limited clinical usefulness because of low sensitivity and specificity.

Presenting features

Patients with significant amount of disease will have symptoms of shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness, and/or wheezing. Those with less significant disease will have no respiratory symptoms. In these cases, the disease may be detected on a routine chest x-ray. People working with beryllium may be asymptomatic, and present requesting a beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT).

Haemoptysis, night sweats, and a fever may be the initial presentation where pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) develops as a complication of silica exposure. Haemoptysis with or without weight loss may also be a symptom of lung cancer. Presentation may uncommonly be with non-respiratory symptoms, such as symptoms of scleroderma or rheumatoid arthritis (uncommon complications of silica or coal exposure).

Mostly, symptoms develop chronically. However, rarely, exposed individuals will present with acute conditions. Symptoms of accelerated silicosis are the same as symptoms of chronic silicosis, but they develop at a faster rate. Symptoms of acute silicosis (alveolar proteinosis) are more severe and occur within weeks or months of high silica exposure. An acute form of berylliosis may present as pneumonitis, with acute wheezing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

Physical examination

Physical findings will be normal early in these diseases. There is nothing on physical examination that is specific for the pneumoconioses. Prolonged expiration and wheezing may be heard in silica- and coal-exposed workers who develop COPD. Widespread wheeze is also present on chest examination with acute berylliosis. Crackles may be heard with chronic beryllium disease. With progressive massive fibrosis, areas of dullness may be appreciated on chest percussion. As with other respiratory diseases, as the disease progresses, the patient may be cyanotic, develop a barrel chest, and have weight loss. Clubbing of fingers and toes may occur as the severity of the condition increases. Non-respiratory signs, such as hypertension, oedema, skin changes, joint swelling, tenderness, or deformity may be detected if uncommon complications of silica or coal exposure occur (e.g., renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma).

Investigations

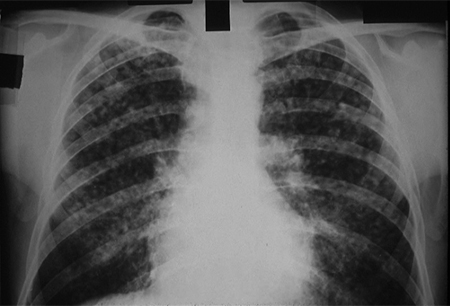

A chest x-ray is the initial screening test in an individual suspected of exposure to silica, coal, or beryllium.[29] It is also the initial test when a patient presents with shortness of breath. Rounded opacities on chest x-ray, first seen in the upper lobes, are characteristic signs in people with silicosis and coal workers' pneumoconiosis.[30][31] A thin layer of calcification around lymph nodes in hilar regions ('egg shell calcification') is an unusual finding, but is specific for silicosis. Linear interstitial changes, initially in the upper lobes, are characteristic x-ray findings in people with chronic beryllium disease. Clinical judgment is key when interpreting the chest x-ray. No radiographical features are pathognomonical, and some unrelated features can mimic those caused by exposure. Diagnosis should only be made in the context of the clinical history and other examination results.

For more detail on the International Labour Office (ILO) classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses, see Diagnostic criteria. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR showing changes consistent with simple silicosis or coal workers' pneumoconiosisFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman, Michigan State University [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR of chronic beryllium diseaseFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman, Michigan State University [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CXR of chronic beryllium diseaseFrom the personal collection of Kenneth D. Rosenman, Michigan State University [Citation ends].

Pulmonary function testing (spirometry, lung volumes, resistance, conductance, and diffusing capacity) is indicated in all patients with:

Radiographic changes

Significant silica, coal, or beryllium exposure

Symptoms of shortness of breath.

The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society have produced joint guidelines on best practice for spirometry. ATS/ERS: standardization of spirometry 2019 update Opens in new window

Depending on the severity of disease, pulmonary function may be normal or abnormal.[32] A restrictive disease pattern may be present, and is indicated on spirometry by:[30]

Reduced forced vital capacity (FVC), with a normal forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1) to FVC ratio

Reduced vital capacity and total lung capacity

Reduced diffusing capacity.

Patients with silicosis or coal workers' pneumoconiosis commonly have obstructive changes, with a reduced FEV1 and air trapping with increased residual volume.[25][26][33][34] The risk of obstructive changes is increased in patients who have a history of mineral dust exposure and cigarette smoking.[26][34][35] Oxygen saturation and arterial blood gas (ABG) may further define the degree of impairment. Oxygen saturation at rest and after exercise is also useful to determine if a patient needs ongoing oxygen therapy, and is indicated in individuals with changes on pulmonary function testing and/or radiographs.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of the chest is more sensitive than chest x-ray in identifying interstitial fibrosis. It is also more sensitive in detection of progression from simple silicosis or coal workers' pneumoconiosis to progressive massive fibrosis.[35]

Bronchoscopic biopsy generally provides insufficient tissue to rule out silicosis or coal workers' pneumoconiosis. In these two types of pneumoconiosis, its use is limited to the assessment for cancer or other suspected clinical conditions. In contrast, bronchial endoscopy with biopsy and lavage is routinely performed to confirm the diagnosis of chronic beryllium disease.

The BeLPT is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of beryllium sensitisation. This test is an essential component of the diagnosis of chronic beryllium disease in the US. It is typically performed on a blood sample first, and confirmed with a repeat test. Bronchial lavage fluid is tested with the BeLPT and may be positive when the blood test is negative.[13]

Biopsy is rarely needed for the diagnosis. Its use should be limited to situations where cancer is suspected, or where there is an absence of a known history of exposure to the suspected mineral dust. When it is performed in people with silicosis, silicotic nodules are seen. These have concentric, laminated layers of hyaline collagen around central collections of particles of silica. Polarised light is used to identify birefringent silica particles. With progressive massive fibrosis in silicosis, open biopsy reveals a mass of dense, hyalinised connective tissue with minimal silica content, a small amount of anthracotic pigment, minimal cellular infiltrate, and negligible vascularisation. Open biopsy in patients with acute silicosis demonstrates alveolar filling with proteinaceous material consisting largely of phospholipids or surfactants that stain with PAS reagent.

Biopsy appearance in people with coal workers' pneumoconiosis includes focal and discrete changes related to respiratory bronchioles, where phagocytosed particles are aggregated. There is a small amount of reticulin formation. Concomitant focal emphysema is present, due to dilation of the surrounding respiratory bronchioles around a heavily pigmented area. Coal workers' pneumoconiosis with progressive massive fibrosis leads to intense carbon pigmentation, dense fibrosis, endarteritis obliterans of the blood vessels, and extensive areas of necrosis. Some cases of progressive coal workers’ pneumoconiosis have had diffuse interstitial fibrosis with chronic inflammation, focal alveolar proteinosis, and polarised light microscopy revealing large quantities of silica.[36] Open biopsy in people with chronic beryllium disease demonstrates granulomas with a centre composed of epithelioid-like cells. These have an appearance similar to granulomas in sarcoid.

Patients with silicosis should be tested for TB.[37] The risk of active TB is even greater in those mining populations with a high prevalence of HIV infection.[38] See Pulmonary tuberculosis (Diagnostic approach).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer