Approach

Strongyloides infection persists lifelong if not adequately treated, due to its unique auto-infective cycle. The diagnosis of strongyloidiasis needs to be considered in all residents or people migrating from areas where the disease is endemic regardless of time since immigration. Definitive diagnosis is by the identification of strongyloides larvae in a clinical specimen. Probable diagnosis is made by positive IgG serology.

In chronic strongyloidiasis, diagnosis is made following identification of larvae in stool.

Strongyloidiasis hyperinfection (a massive infection of larvae within the standard auto-infection cycle of gastrointestinal [GI] to pulmonary tracts) is definitively diagnosed by the identification of Strongyloides from a sputum specimen. A probable diagnosis is made with a compatible clinical syndrome (pulmonary pneumonitis) in conjunction with identification of stool larvae.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis (hyperinfection with dissemination of larvae to non-GI and non-pulmonary locations, such as muscle or central nervous system) is diagnosed with the identification of strongyloides larvae in another clinical specimen or biopsy from a source not part of the routine strongyloides life cycle of pulmonary and GI tracts.

Identification of risk factors

The greatest risk factor is cutaneous exposure to infected soil containing strongyloides filariform larvae. Infection is endemic in many tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, including the Appalachia region of the US, and certain Mediterranean areas, especially Catalonia, Spain. Agricultural workers are at primary risk. In non-endemic regions, 99% of chronic strongyloides infections are among migrants from endemic areas, particularly refugees.[11][12][13][14][15][16] Most routine international tourists are not at high risk of strongyloides; however, an unexplained eosinophilia should be evaluated.[19]

Risk of life-threatening hyperinfection is primarily related to immunosuppression, particularly with corticosteroids.[20][21]

Initial presentation

People with chronic strongyloidiasis are most frequently asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. The infection may only be detected because eosinophilia is seen incidentally on a full blood count (FBC) carried out as part of the investigation of another condition. However, the disease can present with a variety of diverse and often vague clinical symptoms including:[11]

Abdominal pain (40%), which is usually chronic and vague

Pulmonary complaints, such as wheezing or cough (22%)

Stool changes, such as diarrhoea or constipation (20%)

Weight loss (18%); malabsorption is associated with strongyloides

Dermatitis or pruritus (14%).

Other less common skin manifestations are various and include:

Larva currens (a rapidly moving serpiginous, pruritic urticarial rash, moving 5-10 cm/hour)

Cutaneous larva migrans (slower-moving rash)

Rashes mimicking a drug reaction

Purpuric rash associated with disseminated infection.

In one US case series, 20% of individuals were asymptomatic and detected by incidental screening.[11] Co-infection with other parasites is common.[11]

Clues for strongyloides include an FBC result revealing persistence of eosinophilia following treatment for the other parasite. Giardia with eosinophilia necessitates that the diagnosis of strongyloides infection is considered as giardia does not cause eosinophilia.

Rarely, patients may develop features of inflammatory bowel disease. Adult larvae in the duodenum may cause a severe duodenitis evident in histology with villi atrophy and plasma cells infiltration. Colonic manifestations can clinically mimic ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease with eosinophilic granulomatous inflammation affecting the colonic wall.

People who have migrated from endemic areas who have chronic strongyloides infection and are started on corticosteroids may develop life-threatening hyperinfection. Typical presenting symptoms and signs are fever, cough, wheezing, and/or abdominal pain. Patients often rapidly become critically ill with bacteraemia and sepsis from an enteric organism, such as Escherichia colior enterococcus, and develop signs of septic shock.

Initial investigations

Stool examination for ova and parasites (O&P)

This is the initial diagnostic test. However, a single specimen is <50% sensitive for detecting strongyloides larvae.[11][15] Three stool specimens collected on different days should be examined as shedding of larvae may be intermittent.

Patients presenting with hyperinfection or disseminated infection may have strongyloides larvae detectable in stool or sputum specimens.

FBC

In situations where an eosinophilia on FBC has not already been detected incidentally, an FBC is an initial investigation required in all patients suspected with strongyloidiasis. Consultation with a tropical medicine expert is recommended in all people with unexplained eosinophilia.

An absolute eosinophilia >0.4 × 10⁹ eosinophils/L (>400 eosinophils/microlitre) or relative eosinophilia >5% of the WBC differential cell count, will be present in 80% to 85% of chronically infected individuals.[11][15] Eosinophil counts >0.5 × 10⁹ eosinophils/L (>500 eosinophils/microlitre) are 75% sensitive for strongyloides infection in non-endemic settings.

Eosinophilia is frequently absent (40%) when a patient is receiving corticosteroids and presenting with hyperinfection.[20][21] Absence of eosinophilia is a strong predictor of mortality in people with hyperinfection.

Eosinophilia will resolve within 6 months in successfully treated people.[11]

Serology

In people with unexplained eosinophilia and three negative stool examinations, strongyloides IgG serology can confirm exposure.[15] Commercial or US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) enzyme immunoassays for IgG serology generally have a diagnostic performance of approximately 96% sensitivity and 98% specificity.[31]

Other parasites that are difficult to diagnose should also be considered, such as Paragonimus westermani, a lung fluke typically seen in southeast Asians with pulmonary symptoms, and schistosomiasis and filariasis in sub-Saharan Africans.

Serologies are performed at reference laboratories and there may be a delay before the results become available. The specific assays at reference laboratories are of variable quality, with or without prior performance validation.

Diagnostic standards depend on the local resource availability.[1] The gold standard for diagnosing strongyloidiasis is IgG anti-strongyloides serology and one faecal test, either Baermann or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). For medium-resource settings, diagnosis should include IgG anti-strongyloides serology and a spontaneous tube sedimentation (STS) faecal test. For settings where resources are low, an STS faecal test may be used.

Other investigations

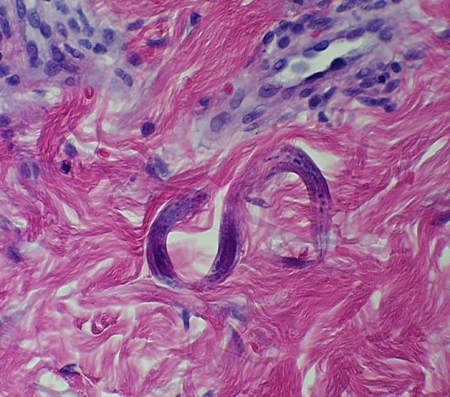

Skin or tissue biopsy

Occasionally skin or tissue biopsy will reveal strongyloides larvae. This is usually an incidental finding from a biopsy performed for other reasons, but skin biopsy should be considered in people migrating from areas where the infection is endemic, especially in people with eosinophilia.

Chest x-ray (CXR)

Pulmonary infiltrates may be present on CXR in people with hyperinfection.

Empirical therapy

In certain situations, empirical therapy with ivermectin may be used as a diagnostic tool. For instance, migrants from endemic areas may present with unexplained eosinophilia, have had a thorough evaluation and may require urgent corticosteroids for an acute condition (e.g., acute asthma). When follow-up is not guaranteed and test results may not be timely, an empirical trial of ivermectin (2 doses) is recommended.

At 6-month follow-up, eosinophilia will have resolved in successfully treated people.[11] At 6-12 months post ivermectin therapy, two-thirds of patients will either have a negative serology or quantitatively the titre will be decreased by 40% or more.

PCR

PCR has been shown to be more sensitive than traditional O&P examinations; however, commercial PCR assays for diagnosing strongyloides infection are not yet widely available.[32]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Strongyloides stercoralis larva in tissueFrom the collection of David Boulware, University of Minnesota; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer