Treatment can be divided into treatment of occupational exposure to the organism, primary prophylaxis, treatment of the active disease, and secondary prophylaxis. Most infections in healthy people are mild and self-limiting and do not need treatment (other than eye disease).

Treatment regimens for children are generally the same as adults, although doses will differ and some of the regimens recommended in adults are not necessarily recommended in children due to a lack of evidence. Consult local paediatric guidelines for further details on the management of children.

Occupational exposure

This group comprises patients exposed to Toxoplasma gondii by contact with infected blood or cell cultures.

Risk should be stratified on the basis of type of exposure (deep needle stick versus needle prick), organism burden (highly concentrated versus fluid of low burden) and genotype (virulent type I strain versus other strain).

Anti-Toxoplasma immunoglobulin (Ig) G should be checked immediately to identify those at risk for acute infection.

All seronegative exposed patients or those with unknown serology should be treated. Most experts would treat all people who have had a definite exposure.

For those with no detectable antibodies, treatment is given for 4 weeks and serology repeated. If seroconversion is documented, patients should be followed clinically. Patients who are seropositive at the onset of treatment, or who are known to have been positive before exposure, are probably partially protected. Most experts would treat high-inoculum deep exposures of a virulent type I strain for 2 weeks. (Type I strains [RH, GT-1] are commonly used laboratory strains that are highly lethal to mice. These genotypes have been associated with outbreaks of retinitis and other serious symptomatic disease in immunocompetent individuals.)

Benefits of treatment include prevention of acute infection. Risks include side effects from medicines.

Women who work in facilities where T gondii is used should have serologies checked at baseline. If negative, they should avoid exposure once pregnant or once planning to become pregnant.

Of note, there are no published guidelines or trials relating to treatment of occupational exposure.

Prophylaxis in patients with HIV

Prophylactic treatment is given to prevent re-activation of latent disease in patients who are immunocompromised.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

All adults and children older than 6 years of age with HIV and CD4+ T lymphocyte counts <100 cells/microlitre, and all children with HIV aged 6 years and younger with CD4% <15%, with detectable anti-Toxoplasma IgG, should receive primary prophylaxis.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

Adults and adolescents living with HIV, especially those with CD4 counts <200 cells/microlitre, should be counselled not to eat raw or undercooked meat or raw shellfish.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

Cat owners with HIV whose CD4 counts are <200 cells/microlitre and who are seronegative are advised to avoid direct contact with cat faeces.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

First-line prophylaxis is trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. This is also the recommended prophylactic regimen for Pneumocystis jiroveci (P carinii) pneumonia. This treatment cannot be used for active disease as there is a high risk of treatment failure. Toxicities include rash, fever, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatotoxicity.

If a patient is allergic to sulfonamides or shows related toxicity (up to 20% of HIV-positive patients develop rash with sulfa-based compounds) alternative prophylactic regimens include: atovaquone; daily or weekly dapsone plus weekly pyrimethamine and calcium folinate; or atovaquone plus pyrimethamine and calcium folinate.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

Primary prophylaxis can be discontinued in children, adolescents, and adults if the patient is taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and has responded with an increase in CD4+ T lymphocyte count to greater than 200 cells/microlitre (or >15% for children under 6 years old) for 3 or more months and plasma HIV RNA is undetectable.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

Additionally, discontinuation of primary prophylaxis can be considered for adolescent and adult patients taking ART with CD4+ T lymphocyte counts between 100 and 200 cells/microlitre if the HIV RNA plasma viral load remains below the limit of detection for at least 3 to 6 months.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

Prophylaxis in transplant recipients

The routine use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for post-transplant prophylaxis of Pneumocystis, regardless of Toxoplasma serostatus, has led to decreased rates of toxoplasmosis in transplant recipients, and is the most frequently used prophylaxis against toxoplasmosis in transplant recipients.[25]Hoz RM La, Morris MI; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Tissue and blood protozoa including toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, Babesia, Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria in solid organ transplant recipients - guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13546.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900295?tool=bestpractice.com

Lifelong prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk heart transplant recipients (where the donor is Toxoplasma IgG positive and the recipient is ToxoplasmaIgG negative). There are very few data supporting prophylactic regimens, other than trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, for toxoplasmosis in the transplant population. In sulfa-allergic patients who are not deficient in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, an alternative prophylaxis regimen is dapsone plus pyrimethamine and calcium folinate. If there is a contraindication to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, consult an infectious diseases specialist for advice on alternative regimens.[25]Hoz RM La, Morris MI; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Tissue and blood protozoa including toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, Babesia, Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria in solid organ transplant recipients - guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13546.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900295?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment of active disease in patients who are immunocompromised

The goal of treatment is to prevent death due to disseminated disease and to prevent/limit damage to specific organs affected by disease.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

Pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine plus calcium folinate is the treatment of choice. If sulfadiazine sensitivity develops, clindamycin can be given in its place. Other treatment regimens include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; atovaquone plus pyrimethamine plus calcium folinate; atovaquone plus sulfadiazine; or atovaquone alone.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

These alternative regimens have not been rigorously studied and should not be used without consultation with an infectious diseases specialist. Adjunctive corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone, prednisolone) should only be given to treat mass effect or associated oedema, and should be discontinued as soon as clinically feasible.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

Initial treatment duration for all patients who are immunocompromised is 6 weeks, but the duration may be longer if central nervous system (CNS) lesions have not significantly improved.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

In transplant recipients, it is common practice to reduce immunosuppressive therapy whenever possible and allow treatment to be guided by extensive literature on the treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS.[25]Hoz RM La, Morris MI; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Tissue and blood protozoa including toxoplasmosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, Babesia, Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria in solid organ transplant recipients - guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33(9):e13546.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900295?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment failure is suggested by clinical or radiographic worsening (as in the case of increasing size of brain lesions with encephalitis) after 1 week of therapy or failure to clinically or radiographically improve after 2 weeks of treatment. If this occurs, a brain biopsy should be performed. If subsequent brain biopsy confirms toxoplasmic encephalitis, consider changing therapy to one of the alternative regimens.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

After completing initial treatment, patients should continue to receive secondary prophylaxis to prevent re-activation of disease for as long as they remain immunocompromised. Secondary prophylaxis may be stopped in adults and adolescents with HIV when the patient is asymptomatic of signs or symptoms of encephalitis and has maintained a CD4+ count >200 cells/microlitre for at least 6 months in response to antiretroviral therapy.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

Pregnant patients with suspected or confirmed acute infection

The goal of treatment is to prevent or limit the severity of infection in the fetus for pregnancies that are not terminated.

Women infected during the first 18 weeks of pregnancy can be treated with spiramycin to lower the risk of transmission to the fetus.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

[48]Daffos F, Forestier F, Capella-Pavlovsky M, et al. Prenatal management of 746 pregnancies at risk for congenital toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med. 1988 Feb 4;318(5):271-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3336419?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Peyron F, L'ollivier C, Mandelbrot L, et al. Maternal and congenital toxoplasmosis: diagnosis and treatment recommendations of a French Multidisciplinary Working Group. Pathogens. 2019 Feb 18;8(1):24.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6470622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30781652?tool=bestpractice.com

Amniotic fluid PCR assay should be done at ≥4 weeks after acute primary maternal infection and at ≥18 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of false negative results. If there is no documented infection in the fetus, spiramycin should be continued until delivery, as placental infection remains a risk and transmission could still occur during the pregnancy.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

Spiramycin is estimated to reduce the incidence of vertical transmission by 60%.[16]Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004 Jun 12;363(9425):1965-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15194258?tool=bestpractice.com

Of note, spiramycin is not effective monotherapy if infection has already spread to the fetus.

If maternal infection occurs after 18 weeks gestation, or fetal transmission has been documented on amniotic fluid PCR at ≥18 weeks gestation, therapy with pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine/calcium folinate should be started.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

[50]Mandelbrot L, Kieffer F, Sitta R, et al. Prenatal therapy with pyrimethamine + sulfadiazine vs spiramycin to reduce placental transmission of toxoplasmosis: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;219(4):386.e1-386.e9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29870736?tool=bestpractice.com

Spiramycin does not cross the placenta and therefore is not suitable for treatment of the fetus. Ultrasound follow-up should include examination of the fetus every 4 weeks, with a focus on brain, eye, and growth assessment.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

[51]Khalil A, Sotiriadis A, Chaoui R, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: role of ultrasound in congenital infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul;56(1):128-51.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/uog.21991

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32400006?tool=bestpractice.com

Full blood counts should be monitored frequently in patients taking pyrimethamine. Calcium folinate dose can be increased if megaloblastic anaemia, granulocytopenia, or thrombocytopenia develops.

Congenital disease

The goal of treatment is to prevent or limit pathology in the CNS and eye. Treatment that is started early (before 2.5 months of age) and that is continued for 12 months appears to result in more favourable outcomes, in particular reducing the likelihood of sensorineural hearing loss.[52]Brown ED, Chau JK, Atashband S, et al. A systematic review of neonatal toxoplasmosis exposure and sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 May;73(5):707-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19215990?tool=bestpractice.com

Infected newborns should be treated for 1 year with pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine plus calcium folinate.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full

[53]McLeod R, Boyer K, Karrison T, et al. Outcome of treatment for congenital toxoplasmosis, 1981-2004: the National Collaborative Chicago-Based, Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 May 15;42(10):1383-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16619149?tool=bestpractice.com

Pyrimethamine dose may need to be decreased and calcium folinate dose may need to be increased if there is evidence of bone marrow suppression or the inability to tolerate the oral drug because of excessive gastrointestinal side effects (nausea, vomiting).

An alternative regimen for those who develop allergy to sulfonamides is pyrimethamine plus calcium folinate plus clindamycin.[54]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toxoplasmosis: clinical care of toxoplasmosis. Jan 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.cdc.gov/toxoplasmosis/hcp/clinical-care/index.html

There are very limited clinical data available to allow for further recommendations.

Prednisolone may be given with pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine in patients with an elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein (>10 g/L [1 g/dL]) or when active chorioretinitis threatens vision.[11]Maldonado YA, Read JS, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20163860.

https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/139/2/e20163860/59988/Diagnosis-Treatment-and-Prevention-of-Congenital

Corticosteroids are continued until resolution of elevated CSF protein or active chorioretinitis, at which time they should be quickly tapered.

Ophthalmic disease

The goal of treatment is to limit the amount of damage to the affected area of the eye and to limit the duration of symptoms. There are few randomised controlled trials pertaining to treatment of toxoplasmic chorioretinitis. One systematic review concluded that antibiotic treatment probably reduces the risk of recurrent toxoplasmic chorioretinitis, but there was a lack of evidence that antibiotics resulted in better visual outcomes, and there were no data evaluating the effects of adjunctive corticosteroids.[55]Pradhan E, Bhandari S, Gilbert RE, et al. Antibiotics versus no treatment for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 20;(5):CD002218.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002218.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198629?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Jasper S, Vedula SS, John SS, et al. Corticosteroids as adjuvant therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 26;(1):CD007417.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5369355

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28125765?tool=bestpractice.com

Despite a lack of evidence to support routine antibiotic treatment, treatment is warranted for severe or persistent lesions involving the macula or optic nerve, for large retinal lesions with severe inflammation, and for any lesion in an individual who is immunocompromised.[55]Pradhan E, Bhandari S, Gilbert RE, et al. Antibiotics versus no treatment for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 20;(5):CD002218.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002218.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198629?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Jasper S, Vedula SS, John SS, et al. Corticosteroids as adjuvant therapy for ocular toxoplasmosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 26;(1):CD007417.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5369355

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28125765?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Stanford MR, See SE, Jones LV, et al. Antibiotics for toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: an evidence-based systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2003 May;110(5):926-31;quiz 931-2.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12750091?tool=bestpractice.com

There is some controversy as to whether to treat small, peripheral retinal lesions in a person who is immunocompetent.

In patients who are immunocompetent, both congenital and acquired ocular diseases are treated with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, calcium folinate, and prednisolone.

Corticosteroids are continued until inflammation subsides (usually 1 to 2 weeks) and then quickly tapered. Pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine should be continued for 1 to 2 weeks after signs and symptoms of active disease have resolved in a person who is immunocompetent. Calcium folinate should be continued for 1 week after cessation of pyrimethamine. There is no confirmed treatment to prevent recurrence of disease, which can occur in up to 10% of cases, although trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has been used for chronic suppression with some effect.[58]Silveira C, Belfort R, Muccioli C, et al. The effect of long-term intermittent trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment on recurrences of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002 Jul;134(1):41-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12095806?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Kim SJ, Scott IU, Brown GC, et al. Interventions for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2013 Feb;120(2):371-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23062648?tool=bestpractice.com

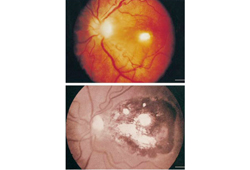

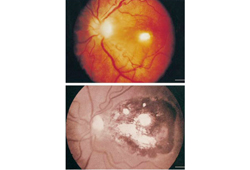

Patients who are immunocompromised with isolated ophthalmic disease should receive the above treatment, followed by chronic suppressive therapy for the duration of their immunosuppression.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pre- and post-treatment retinochoroiditisFrom the collection of Rima L. McLeod, MD, and published in: Roberts F, McLeod R. Pathogenesis of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Parasitol Today. 1999 Feb;15(2):51-7; used with permission [Citation ends].

Prevention of recurrence

Patients who are immunosuppressed who have completed initial therapy for toxoplasmosis should continue to take lifelong secondary prophylaxis unless immune reconstitution occurs in HIV-infected patients as a result of ART or immunosuppressive medicines are stopped. Adherence to chronic maintenance therapy is often difficult for patients, as it comprises multiple medications with frequent dosing schedules.

The recommended regimen for secondary prophylaxis is pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine plus calcium folinate. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is also an option. Alternative regimens for patients allergic to sulfonamides include clindamycin plus pyrimethamine plus calcium folinate, atovaquone plus sulfadiazine, or atovaquone with or without pyrimethamine and calcium folinate.[24]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV: toxoplasmosis. Dec 2024 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/introduction

If immune reconstitution occurs after initiation of ART with sustained CD4+ T lymphocyte counts >200 cells/microlitre for 6 months or greater, consider stopping chronic maintenance therapy. The safety of discontinuing maintenance therapy in children has not been studied, but US guidelines suggest considering stopping chronic maintenance therapy in children younger than 6 years old with sustained CD4+ T lymphocytes >15% and in children aged 6 years and older with sustained CD4+ T lymphocyte counts >200 for 6 or more months.[47]National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Children with and Exposed to HIV. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in children with and exposed to HIV: toxoplasmosis. Oct 2015 [internet publication].

https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-pediatric-opportunistic-infections/toxoplasmosis?view=full