Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) commonly presents rapidly and aggressively in adults. It may mimic many other conditions, which often creates diagnostic confusion.

A definitive diagnosis can be made from a bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy. Leukaemic lymphoblasts may circulate in the blood; if present in sufficient numbers, this may be used to defer bone marrow examination at presentation.

Clinical presentation and history

The appearance of constitutional symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss) or signs and symptoms of cytopenias is often the initial cause for seeking medical attention by patients with ALL. Most patients present within a few weeks of symptom onset.

Anaemia typically manifests as fatigue, dyspnoea, palpitations, and dizziness; thrombocytopenia presents with bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, heavy menstrual bleeding) and easy bruising; neutropenia presents as recurrent infections, which may cause fever.

Lymph node involvement is common in ALL. Enlarged lymph nodes can be an initial presenting sign.

Abdominal and bone pain may be present due to infiltration of leukaemic lymphoblasts in the spleen and bone marrow, respectively.[51]Gallagher DJ, Phillips DJ, Heinrich SD. Orthopedic manifestations of acute pediatric leukemia. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996 Jul;27(3):635-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8649744?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical features that are less common at presentation include eosinophilia, isolated renal failure, pulmonary nodules, bone marrow necrosis, pleural/pericardial effusion, superior vena cava obstruction, hypoglycaemia, joint pain, and skin nodules.[1]Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 8;350(15):1535-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15071128?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Haferlach T, Bacher U, Kern W, et al. Diagnostic pathways in acute leukemias: a proposal for a multimodal approach. Ann Hematol. 2007 May;86(5):311-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17375301?tool=bestpractice.com

Genetic factors associated with the development of ALL

Historical factors suggestive of ALL include history of malignancy, family history of ALL, genetic disorder (e.g., trisomy 21, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Klinefelter syndrome, Fanconi's anaemia, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Bloom syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia), treatment with chemotherapy, radiation exposure, smoking, and viral infections (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus).[1]Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 8;350(15):1535-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15071128?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Jabbour EJ, Faderl S, Kantarjian HM. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005 Nov;80(11):1517-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16295033?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, et al. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood. 2003 Oct 1;102(7):2321-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12791663?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Machatschek JN, Schrauder A, Helm F, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and Klinefelter syndrome in children: two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004 Oct-Nov;21(7):621-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15626018?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Bloom M, Maciaszek JL, Clark ME, et al. Recent advances in genetic predisposition to pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020 Jan;13(1):55-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31657974?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Strevens MJ, Lilleyman JS, Williams RB. Shwachman's syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br Med J. 1978 Jul 1;2(6129):18.

https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/2/6129/18.1.full.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/277273?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Woods WG, Roloff JS, Lukens JN, et al. The occurrence of leukemia in patients with the Shwachman syndrome. J Pediatr. 1981 Sep;99(3):425-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7264801?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Snyder DS, Stein AS, O'Donnell MR, et al, Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia secondary to chemoradiotherapy for Ewing sarcoma. Report of two cases and concise review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2005 Jan;78(1):74-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15609284?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Guan H, Miao H, Ma N, et al. Correlations between Epstein-Barr virus and acute leukemia. J Med Virol. 2017 Aug;89(8):1453-1460.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28225168?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]De Keersmaecker K, Marynen P, Cools J. Genetic insights in the pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2005 Aug;90(8):1116-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16079112?tool=bestpractice.com

[52]Hoelzer D, Gökbuget N, Ottmann O, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002 Jan;(1):162-92.

https://ashpublications.org/hematology/article/2002/1/162/18610/Acute-Lymphoblastic-Leukemia

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12446423?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Findings may include pallor, ecchymoses, petechiae, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, mediastinal masses, abdominal masses, testicular enlargement (unilateral and painless), renal enlargement, and skin infiltrations (skin nodules).

Lymphadenopathy is classically generalised, and the enlarged nodes are painless and freely movable.[1]Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 8;350(15):1535-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15071128?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Haferlach T, Bacher U, Kern W, et al. Diagnostic pathways in acute leukemias: a proposal for a multimodal approach. Ann Hematol. 2007 May;86(5):311-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17375301?tool=bestpractice.com

T-ALL more commonly causes mediastinal masses, whereas B-ALL more commonly causes abdominal masses. The findings of stridor, wheezing, pericardial effusion, and superior vena cava syndrome may be associated with mediastinal masses. Mature B-ALL (Burkitt's lymphoma/leukaemia) may initially present as a palpable large abdominal mass from a rapidly proliferating tumour.[34]Hoffman R, Shattil SJ, Furie B, et al. Hematology: basic principles and practice. Vol 1. 4th ed. Orlando, FL: Churchill Livingstone / W.B. Saunders; 2005.[53]Abeloff MD, Armitage J, Niederhuber JE, et al. Clinical oncology. 3rd ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2004:3232.

Testicular involvement occurs most commonly in children and adolescents with T-ALL.[54]Nguyen HTK, Terao MA, Green DM, et al. Testicular involvement of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and adolescents: diagnosis, biology, and management. Cancer. 2021 Sep 1;127(17):3067-81.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.33609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34031876?tool=bestpractice.com

Testicular examination should be carried out at diagnosis in all male patients. The testes can represent a sanctuary site that is relatively protected from the effects of systemic therapy via the blood-testis barrier.[54]Nguyen HTK, Terao MA, Green DM, et al. Testicular involvement of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and adolescents: diagnosis, biology, and management. Cancer. 2021 Sep 1;127(17):3067-81.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.33609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34031876?tool=bestpractice.com

Neurological assessment

Required to exclude central nervous system (CNS) involvement, which is a major complication of ALL. CNS involvement occurs in approximately 5% to 7% of patients at diagnosis; incidence is highest in patients with T-ALL (8%) and mature B-ALL (Burkitt's lymphoma/leukaemia, 13%).[9]Pui CH. Central nervous system disease in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: prophylaxis and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006 Jan;(1):142-6.

https://ashpublications.org/hematology/article/2006/1/142/19688/Central-Nervous-System-Disease-in-Acute

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17124053?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Reman O, Pigneux A, Huguet F, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis and/or at first relapse: results from the GET-LALA group. Leuk Res. 2008 Nov;32(11):1741-50.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18508120?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Lazarus HM, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis: results from the international ALL trial MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2006 Jul 15;108(2):465-72.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/108/2/465/109893/Central-nervous-system-involvement-in-adult-acute

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16556888?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Lamanna N, Weiss M. Treatment options for newly diagnosed patients with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Hematol Rep. 2004 Jan;3(1):40-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14695849?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Richards S, Pui CH, Gayon P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials of central nervous system directed therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013 Feb;60(2):185-95.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pbc.24228

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22693038?tool=bestpractice.com

The meninges are the primary site of CNS disease.[59]Frishman-Levy L, Izraeli S. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of CNS acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and potential for therapy. Br J Haematol. 2017 Jan;176(2):157-67.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.14411

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27766623?tool=bestpractice.com

Presenting features of CNS disease include mental status changes, focal neurological signs/deficits (e.g., diplopia, chin numbness), headache, papilloedema, nuchal rigidity, and meningismus.[3]Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017 Jun 30;7(6):e577.

https://www.nature.com/articles/bcj201753

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28665419?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Deak D, Gorcea-Andronic N, Sas V, et al. A narrative review of central nervous system involvement in acute leukemias. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Jan;9(1):68.

https://atm.amegroups.org/article/view/59808/html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33553361?tool=bestpractice.com

[8]Del Principe MI, Maurillo L, Buccisano F, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: diagnostic tools, prophylaxis, and therapy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6(1):e2014075.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25408861?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial laboratory tests

Should include full blood count with differential, peripheral blood smear, comprehensive metabolic panel (serum electrolytes; serum uric acid; serum lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]; renal function tests; liver function tests), coagulation profile (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, and D-dimers), blood group and antibody screening (for transfusion support), and viral antibody testing (including hepatitis B and C, and HIV serologies).[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[61]RM Partners. Pan-London haemato-oncology clinical guidelines. Acute leukaemias and myeloid neoplasms. Part 1: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Jan 2020 [internet publication].

https://rmpartners.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Pan-London-ALL-Guidelines-Jan-2020.pdf

Laboratory findings

Over 90% of patients have clinically evident haematological abnormalities at the time of initial diagnosis.

Normocytic normochromic anaemia with low reticulocyte count is present in 80% of patients. Thrombocytopenia is very common, affecting 75% of patients.[1]Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004 Apr 8;350(15):1535-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15071128?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Haferlach T, Bacher U, Kern W, et al. Diagnostic pathways in acute leukemias: a proposal for a multimodal approach. Ann Hematol. 2007 May;86(5):311-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17375301?tool=bestpractice.com

Leukocytosis is found in 50% of patients; in 25% of these patients, white blood cell (WBC) count is >50 × 10⁹/L (>50,000/microlitre). High WBC at presentation is associated with a poorer prognosis. Despite the elevation in WBC, many patients have severe neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <0.5 × 10⁹/L [<500 cells/microlitre]), thus placing them at high risk for serious infections.[62]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_3

See Febrile neutropenia.

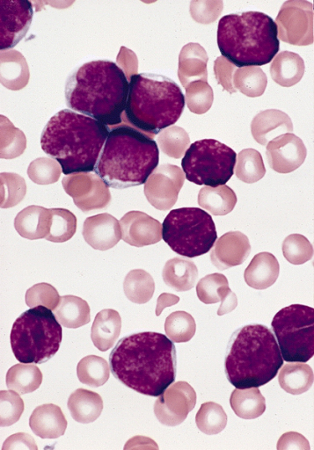

Leukaemic lymphoblasts may be detected on peripheral blood smear. The presence of leukaemic lymphoblasts ≥1 × 10⁹/L (≥1000/microlitre) in the peripheral blood is sufficient to defer bone marrow examination at presentation.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Hypercalcaemia may occur due to bony infiltration or ectopic release of a parathyroid hormone-like substance.

Hyperkalaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hyperuricaemia, hypocalcaemia, and elevated serum LDH may occur due to tumour lysis syndrome (TLS), particularly during treatment and if WBC count (tumour burden) is high. This can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, acute renal failure, and death, if untreated. TLS is an oncological emergency. See Tumour lysis syndrome.

Evaluation of bone marrow

The diagnostic work-up for ALL requires haematopathology evaluation of bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy specimens (or peripheral blood if sufficient numbers of circulating lymphoblasts are present), which should include:[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[63]de Haas V, Ismaila N, Advani A, et al. Initial diagnostic work-up of acute leukemia: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of the College of American Pathologists and American Society of Hematology guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jan 20;37(3):239-53.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.18.01468

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30523709?tool=bestpractice.com

These investigations can determine the subtype of ALL; inform risk stratification and treatment planning; and establish a baseline for measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment during treatment (see below).[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Cytomorphology assessment

A biopsy demonstrating bone marrow hypercellularity and infiltration by lymphoblasts is characteristic for ALL.

There is a lack of consensus regarding the proportion of lymphoblasts in the bone marrow that is required to make a diagnosis of ALL; however, a threshold of ≥20% is generally advised.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Note that defined lymphoblast threshold in the bone marrow (or peripheral blood) is not always required for the diagnosis of ALL (e.g., T-ALL can be diagnosed based on immunophenotyping). See Classification.

The proportion of lymphoblasts in the bone marrow can help distinguish between ALL and lymphoblastic lymphoma. See Differential diagnosis.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) cytochemical staining of biopsy specimens should be performed to help differentiate ALL from acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). MPO will be negative in ALL and positive in AML.[64]Gökbuget N, Boissel N, Chiaretti S, et al. Diagnosis, prognostic factors, and assessment of ALL in adults: 2024 ELN recommendations from a European expert panel. Blood. 2024 May 9;143(19):1891-902.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/143/19/1891/514792/Diagnosis-prognostic-factors-and-assessment-of-ALL

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38295337?tool=bestpractice.com

See Differential diagnosis.

Immunophenotypic findings

Immunophenotyping (on bone marrow specimens, or peripheral blood if sufficient numbers of circulating lymphoblasts are present) is required to assess cell markers to:[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

determine lymphoid lineage (B-cell or T-cell);

define an aberrant phenotype for MRD assessment; and

detect cell surface antigens of clinical and therapeutic importance (e.g., CD20).

Leukaemic cells typically exhibit markers of one cell type. Rarely, simultaneous expression of lymphoid and myeloid markers occurs in ALL, either as ALL with aberrant expression of myeloid antigens (My+ ALL) or true biphenotypic acute leukaemia.

Cytogenetic and molecular evaluation

Cytogenetic analysis (e.g., karyotyping; fluorescence in situ hybridisation [FISH]) and molecular testing (e.g., reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]) of leukaemic lymphoblasts (on bone marrow or peripheral blood specimens) are required to detect recurrent genetic abnormalities (e.g., BCR::ABL1 [Philadelphia chromosome]; KMT2A rearrangements).[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[63]de Haas V, Ismaila N, Advani A, et al. Initial diagnostic work-up of acute leukemia: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of the College of American Pathologists and American Society of Hematology guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jan 20;37(3):239-53.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.18.01468

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30523709?tool=bestpractice.com

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays can be used alongside cytogenetic analysis and RT-PCR testing to detect additional gene fusions/rearrangements (e.g., DUX4, MEF2D, ZNF384) and pathogenic mutations (e.g., SH2B3, IL7R, and JAK1/2/3 in Philadelphia chromosome-like B-ALL [Ph-like B-ALL]).[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[63]de Haas V, Ismaila N, Advani A, et al. Initial diagnostic work-up of acute leukemia: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of the College of American Pathologists and American Society of Hematology guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jan 20;37(3):239-53.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.18.01468

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30523709?tool=bestpractice.com

Comprehensive cytogenetic and molecular characterisation of leukaemic lymphoblasts (alongside haematopathology evaluation of bone marrow) determines the subtype of ALL; informs risk stratification and treatment planning; and facilitates MRD assessment.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[63]de Haas V, Ismaila N, Advani A, et al. Initial diagnostic work-up of acute leukemia: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of the College of American Pathologists and American Society of Hematology guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jan 20;37(3):239-53.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.18.01468

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30523709?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lymphoblasts in bone marrow smear from 3-year-old male with ALL (Wright-Giemsa stain)Image and description are from the AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology [Citation ends].

Baseline measurable residual disease (MRD) testing

It is important to establish a baseline for MRD testing based on immunophenotypic and molecular features of the leukaemic lymphoblast.

MRD testing enables depth and speed of remission to be assessed during treatment. It is prognostically important and can guide therapeutic decisions. The method used for MRD testing depends on the patient, and the assays available to the treating centre.

The preferred sample for MRD testing is the first small volume (of up to 3 mL) pull of the bone marrow aspirate, if feasible.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture is required in all patients given the frequency of CNS involvement. The procedure should only be performed once raised intracranial pressure has been ruled out.

Lumbar puncture should be carried out at a time consistent with the treatment protocol being used. Paediatric-inspired protocols typically include lumbar puncture at diagnostic work-up. However, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network ALL Panel recommends the first lumbar puncture be performed concomitantly with initial intrathecal therapy to avoid seeding the CNS with circulating leukaemic lymphoblasts, unless symptoms require a lumbar puncture to be performed earlier.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Detection of lymphoblasts in the initial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample by multi-parameter flow cytometry can identify patients at high risk of CNS relapse.[71]Del Principe MI, Buzzatti E, Piciocchi A, et al. Clinical significance of occult central nervous system disease in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A multicenter report from the Campus ALL Network. Haematologica. 2021 Jan 1;106(1):39-45.

https://haematologica.org/article/view/9587

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31879328?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Garcia KA, Cherian S, Stevenson PA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid flow cytometry and risk of central nervous system relapse after hyperCVAD in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2022 Apr 1;128(7):1411-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34931301?tool=bestpractice.com

CNS involvement at diagnosis can be graded based on the presence of lymphoblasts, WBCs, and red blood cells (RBCs) in the CSF, using the Children’s Oncology Group classification.[73]Winick N, Devidas M, Chen S, et al. Impact of initial CSF findings on outcome among patients with National Cancer Institute standard- and high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 1;35(22):2527-34.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.4774

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28535084?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Kopmar NE, Cassaday RD. How I prevent and treat central nervous system disease in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2023 Mar 23;141(12):1379-88.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/141/12/1379/493851/How-I-prevent-and-treat-central-nervous-system

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36548957?tool=bestpractice.com

Higher grade (i.e., increased lymphoblasts, WBCs, and RBCs [traumatic lumbar puncture] in the CSF) is associated with poorer outcomes. See Diagnostic criteria.

Imaging

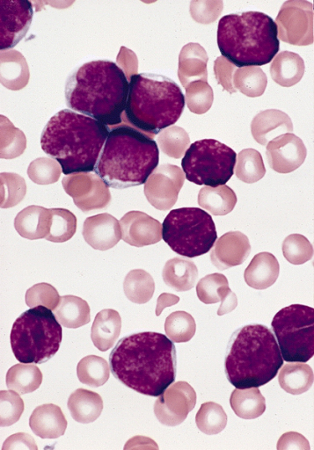

Chest radiograph may be performed to identify a mediastinal mass, pleural effusion, or lower respiratory tract infection.[75]Smith WT, Shiao KT, Varotto E, et al. Evaluation of chest radiographs of children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr. 2020 Aug;223:120-127.e3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32711740?tool=bestpractice.com

Pleural effusions should be tapped and samples sent for cytology and immunophenotyping. A mediastinal biopsy should be avoided if possible, though this may be the primary site of involvement for some patients and in such cases is unavoidable.

CNS imaging (e.g., computed tomography [CT]/magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of head) should be performed in patients with major neurological signs and symptoms (e.g., lowered consciousness level, meningismus, or focal neurological signs/deficits) to identify meningeal involvement or CNS bleeding.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Spinal cord and parenchymal brain involvement may occur, but is very rare.

CT thorax should be performed in the presence of a widened mediastinum on chest radiograph. CT neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed if there is palpable lymphadenopathy or other evidence of extramedullary disease.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

In males with an abnormal testicular examination or symptoms, scrotal ultrasound should be performed to characterise the nature of the abnormality and to establish a baseline prior to treatment initiation.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Echocardiogram or multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan should be considered in all patients to assess cardiac function before initiating treatment.[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Anthracyclines are used in most treatment regimens for ALL and are potentially cardiotoxic.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray of patient presenting with dyspnoea, showing widened mediastinum and tracheal displacementFrom the personal collection of CR Kelsey [Citation ends].

Other investigations

The following tests may be carried out once a diagnosis of ALL is confirmed:[60]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: acute lymphoblastic leukemia [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[76]Relling MV, Schwab M, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for thiopurine dosing based on TPMT and NUDT15 genotypes: 2018 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019 May;105(5):1095-105.

https://ascpt.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpt.1304

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30447069?tool=bestpractice.com

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-typing

Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) phenotyping

Nudix hydrolase 15 (NUDT15) phenotyping

HLA-typing is required to identify a suitable donor for stem cell transplantation and for obtaining HLA-matched platelets in the event of platelet alloimmunisation during platelet transfusion.

TPMT and NUDT15 phenotyping help to guide dosing of mercaptopurine during maintenance therapy.[76]Relling MV, Schwab M, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for thiopurine dosing based on TPMT and NUDT15 genotypes: 2018 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019 May;105(5):1095-105.

https://ascpt.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpt.1304

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30447069?tool=bestpractice.com