Approach

The evaluation of chronic diarrhoea can be difficult and effective assessment requires significant clinical acumen. Approach to evaluation is initially for the most common and most serious conditions, adjusting for history and clinical presentation. If the initial evaluation fails to produce an aetiology, then diagnosis can be pursued in a systematic fashion in order to search for each differential diagnosis.

Historical and symptomatic considerations

Evaluation begins with a thorough history with attention to symptoms, onset and duration, travel history, concurrent medical problems, diet (e.g., lactose, fructose, gluten, etc.), and medication use.[4] The documentation of stool consistency can be facilitated with the “Bristol stool chart”.[5] Bristol stool chart Opens in new window

The key components of the history include:

Duration of diarrhoea: more than 4 weeks in chronic diarrhoea[1]

Number of episodes per day: ≥3 loose stools per day in chronic diarrhoea[1]

Waking at night with symptoms: makes functional disorders less likely

Presence of blood in the stool: may signify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), malignancy, or ischaemia.

Associated symptoms can include:

Weight loss/failure to thrive (e.g., coeliac disease, IBD, malignancy, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, chronic pancreatitis, hyperthyroidism, diabetes)

Abdominal pain (e.g., coeliac disease, Crohn's disease, malignancy)

Constipation alternating with diarrhoea (e.g., IBD, faecal impaction with overflow)

Nausea and vomiting (e.g., small bowel Crohn's disease, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, diabetes, faecal impaction)

Haematochezia or melaena (IBD, ischaemia, malignancy)

Skin changes (coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease).

Additional non-specific symptoms can include:

Steatorrhoea (e.g., pancreatic insufficiency, coeliac disease, liver disease, giardiasis)

Abdominal distention/bloating (non-specific, but beware irritable bowel syndrome and small bowel bacterial overgrowth)

Flatulence (non-specific, but beware irritable bowel syndrome and small bowel bacterial overgrowth)

Borborygmi (non-specific)

Anorexia (non-specific)

Increased infections (common variable immune deficiency, HIV).

Medication use causing diarrhoea can include:

Laxative use (may not be volunteered by patient)

Proton pump inhibitors

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Quinine

Antibiotics (beware Clostridium difficile infection)

Certain chemotherapies and other cancer treatments.[6]

Physical examination

Physical examination is usually non-specific.

Key findings are:

Skin rashes, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum, are consistent with coeliac disease or IBD

Lymphadenopathy or abdominal masses suggestive of infection or malignancy

Blood on rectal examination, which is highly suggestive of a mucosal lesion such as IBD or malignancy.

Laboratory evaluation

Laboratory testing should be individualised for risk factors for disease. For instance, parasitic diseases are uncommon in North America and Western Europe in the absence of travel history.

Basic laboratory tests, which are performed in all patients, include FBC, electrolytes, glucose, liver function tests, C-reactive protein, thyroid function tests, coeliac serology, IgA level, and haematinics (B12, folate, ferritin). Faecal calprotectin testing may be considered if available. Faecal calprotectin has been shown to consistently differentiate IBD from irritable bowel syndrome because it has excellent negative predictive value in ruling out IBD in undiagnosed, symptomatic patients.[4][7][8] However, faecal calprotectin can also be elevated in some cases of colorectal cancer, gastrointestinal (GI) infection, or with use of NSAIDs, limiting the test’s specificity.[4]

There are few viral or bacterial infections that cause chronic diarrhoea in an immunocompetent host, but certain parasites such as Giardia are common and should be tested for with a stool sample for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity. The number of stool samples necessary to achieve adequate specificity varies with diagnostic modality. A single sample may be adequate using direct immunofluorescence, whereas 3 samples will be necessary for microscopic examination.

Endoscopic evaluation

In the evaluation of chronic diarrhoea, endoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool and is often routinely requested unless other pathology is evident that requires treatment, for example, severe constipation (this also makes mucosal disease more unlikely).[9] Endoscopy allows the prompt visual assessment of disease severity and extent in IBD and can provide prognostic information.

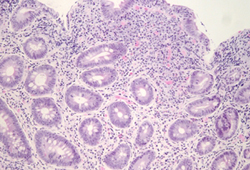

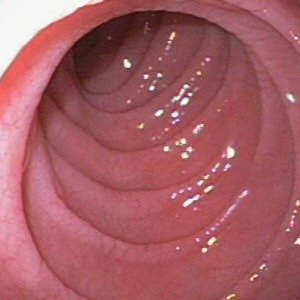

Histological assessment documents the presence of macroscopic and microscopic colitis. Inflammation on colonoscopy can direct future investigations, such as further small bowel evaluation if Crohn's disease is suspected. A negative colonoscopy can allow reassurance to be given to patients who may be concerned they have IBD or cancer. If coeliac disease is suspected, a gastroscopy with duodenal biopsies can be obtained at the same visit.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph of villous atrophy in coeliac diseaseImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic image of scalloping seen in the duodenal mucosa in coeliac disease and other mucosal disorders including giardiasisImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic image of scalloping seen in the duodenal mucosa in coeliac disease and other mucosal disorders including giardiasisImage courtesy of Daniel Leffler, MD and Ciaran Kelly, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Patients with evidence of GI blood loss, anaemia, or significant weight loss should undergo urgent endoscopic assessment of the upper GI tract and large bowel.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer