Approach

The first essential step in evaluating patients with bruising is to obtain a detailed and accurate personal and family history. A thorough history will provide clinicians with a good estimation of the severity of underlying diseases and help to determine the extent of laboratory evaluations required. There are several questionnaires that are used for patient assessment such as the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) Bleeding Assessment Tool (BAT).[29] International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: bleeding assessment tool Opens in new window

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diagnostic algorithm for the work-up of easy bruisingCreated by Tzu-Fei Wang and Eric H. Kraut; used with permission [Citation ends].

History

Personal history of bleeding or bruising with or without haemostatic challenges such as dental extractions, surgeries, or minor/major injuries is one of the most important pieces of information to obtain during the initial evaluation of a patient with easy bruising. Personal and family history of bleeding disorders can help to differentiate between inherited and acquired bleeding disorders.

A family history of known bleeding disorders (e.g., haemophilia, von Willebrand disease [vWD], platelet storage pool disease) or other genetic disorders (e.g., hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia [HHT], Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, MYH9-related disorders, Bernard-Soulier disease, thrombocytopenia with absent radius [TAR] syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) is important. In a study of children referred to a tertiary centre with abnormal coagulation profiles, a positive personal or family history of bleeding was associated with an increased chance of eventual diagnosis of a bleeding disorder.[30] Age and sex may also be important (e.g., actinic purpura [also known as senile purpura] can occur in older people, purpura simplex is more common in females, and haemophilia occurs mostly in males).

The presence of serious underlying disorders (e.g., malignancy, sepsis, obstetric disorders or complications) may suggest the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Hepatitis infection or a history of autoimmune disease may indicate acute liver failure or cirrhosis.

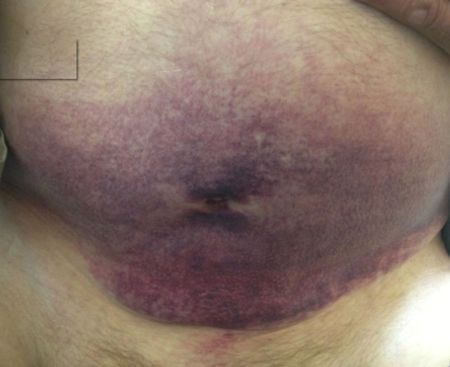

Vitamin deficiencies, such as vitamin C or K, should be considered (e.g., recent hospitalisation, poor diet).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bruising affecting the thigh and pelvic area in a patient with vitamin C deficiencyBMJ Case Reports; doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0750. Copyright © 2014 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends]. The patient should be asked about previous accident and emergency department visits or hospital admissions, history of specialist consultations, and whether there is a history of blood or blood factor transfusions.

The patient should be asked about previous accident and emergency department visits or hospital admissions, history of specialist consultations, and whether there is a history of blood or blood factor transfusions.

Any prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal medications must be asked about in detail and recorded because drugs are a common cause of thrombocytopenia and easy bruising. Anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and antidepressants are common causative agents for bruising.[4][5][6][7][8][9] There are also many drugs that are associated with drug-induced thrombocytopenia. University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: platelets on the web - drug-induced thrombocytopenia Opens in new window Excess or chronic corticosteroid use is associated with Cushing's syndrome, which can be associated with ecchymosis. Alcohol or illicit drug use should also be documented as cirrhosis is a common cause of easy bruising.

For paediatric and older patients, social condition should be assessed in order to ascertain whether there may be a concern for abuse. Features of the history alarming for abuse include recurrent injuries, an unstable home environment, an inconsistent/changing history, and unexplained/inconsistent injuries.

History of bruising/bleeding

The most important factors to consider in regards to the bruising are:

Time of onset and duration

Severity (number and size)

Location.

Time of onset and duration:

Lifelong symptoms indicate congenital or genetic diseases such as haemophilia, vWD, platelet storage pool disease, HHT, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, MYH9-related disorders, Bernard-Soulier disease, TAR syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Recent onset of symptoms indicates acquired diseases such as acquired coagulation inhibitors, external factors (e.g., medications, alcohol abuse, physical abuse), systemic disease (e.g., vasculitis, cirrhosis, acute liver failure), vitamin deficiencies, or bone marrow disorders.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large bruise on the abdomen of a patient on warfarin with acquired factor V inhibitorBMJ Case Reports; doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-010018. Copyright © 2014 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Severity (number and size):

A significant number of bruises (i.e., >5), bruises that are larger in size (i.e., >1 cm), or painful bruises indicate the presence of more severe disorders[29]

Benign conditions such as purpura simplex or actinic purpura usually present with a limited number of bruises that are small in size.

Location:

Spontaneous bruising not associated with trauma and/or bruising in unexposed areas that are generally not subject to trauma are more concerning for severe underlying disease

In benign conditions such as purpura simplex, bruises are usually seen on exposed area(s); while in actinic purpura, the bruises are usually bilateral and on the upper extremities.

Mucosal bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, menorrhagia) is suggestive of a disorder or primary haemostasis (e.g., vWD, platelet disorders, HHT), although it can also be seen in coagulation factor deficiencies. Intra-articular and intramuscular bleeding is suggestive of a severe coagulation factor deficiency (e.g., haemophilia). Epistaxis and menorrhagia can be seen in patients without a bleeding disorder; therefore, an otolaryngology or gynaecology consultation may be warranted. Symptoms of anaemia may be seen in patients with malignancy. B symptoms (e.g., fever, night sweats, weight loss) are specific to lymphoma.

There are several questionnaires that are used for patient assessment such as the ISTH BAT.[29] The tool consists of a series of questions that attempt to objectively quantify the severity of bleeding signs and symptoms in different organ systems or situations (e.g., oral, nasal, skin, gastrointestinal, urinary, joint, muscle, central nervous system, dental, surgery, postnatal, menstrual bleeding). A number from 0-4 is given for each, and the numbers are added together to give a bleeding score. A score ≥4 is abnormal in adult males and a score ≥6 is abnormal in adult females. Abnormal scores should prompt clinicians to pursue a comprehensive work-up.[31]

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: bleeding assessment tool Opens in new window

Physical examination

A full physical examination is required with a focus on signs of bruising or bleeding. The most useful examination sites include:

Mucosa: petechiae or active bleeding/oozing may be noted. Petechiae (tiny, round, non-blanching, pinpoint flat spots <3 mm mostly seen on the lower extremities as a result of bleeding under the skin) are usually only present when the platelet count is extremely low, as seen in quantitative platelet disorders such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), DIC, or bone marrow disorders such as leukaemia or lymphoma.[32] Wet purpura on the buccal mucosa/tongue is suggestive of severe thrombocytopenia.

Skin: number, size, colour (stages of bruising can be determined based on the evolution of bruise colour because bruises typically start as red then progress to purple and then yellow before fading away), and location (exposed versus non-exposed areas) of bruises should be checked. Observe if there are petechiae (usually at lower extremities). Significant bruising is seen in platelet disorders, coagulation factor disorders, and bone marrow disorders. Purpura (larger, palpable petechiae 3-10 mm) may be seen in TTP or vasculitis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bruising in patient with vasculitis (drug-induced)BMJ Case Reports; doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007319. Copyright © 2014 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

Joints: joint flexibility should be evaluated as significantly flexible joints are commonly seen in patients with connective tissue diseases such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan's syndrome. The presence of joint hypermobility can be established directly by calculating the Beighton 9-point score, which is based on the ability to perform a series of manoeuvres. A score of 5 out of 9 or higher is usually taken to indicate generalised hypermobility.[33] Previous recurrent joint bleeds may cause haemarthrosis and limit joint movement; they are usually only seen in severe bleeding disorders such as severe haemophilia or vWD.

Other signs that may point the physician towards a diagnosis include:

Acne, hirsutism, thinning skin, abdominal striae, facial plethora, proximal myopathy, central obesity, and hypertension: Cushing's syndrome

Mucocutaneous telangiectasia: HHT

Ischaemic tissue damage/gangrene: DIC

Jaundice, ascites, spider angioma, abdominal distention, confusion, or splenomegaly: alcohol abuse or acute liver failure/cirrhosis

Hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy: Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome or malignancy

Absent radius bones: TAR syndrome

Burn marks, bone fractures, head injuries, retinal haemorrhage: physical abuse

Dental deterioration, impaired wound healing, coiled hairs: vitamin C deficiency

Tall stature, stretch marks, pectus excavatum (funnel chest), mitral valve murmur, aortic valve murmur: Marfan's syndrome

Hypermobile joints or joint dislocations, hyperextensive or translucent skin: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Signs of haemarthrosis: haemophilia

Signs of anaemia or infection: malignancy.

Laboratory investigations

FBC (with platelet count) should be ordered in all patients. Platelet count will determine the presence and severity of thrombocytopenia. Anaemia (as determined by a low haemoglobin and/or a low haematocrit) in a patient with easy bruising indicates an increased likelihood of a serious or severe cause. Pancytopenia indicates bone marrow disease.

Coagulation studies (e.g., prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) should also be ordered to detect obvious defects in the coagulation pathway. For patients taking warfarin, INR is required to monitor therapeutic level. For patients taking enoxaparin, anti-Xa levels can be used to monitor for therapeutic levels but they are generally only required in selected situations, such as patients with renal insufficiency, Class III obesity (e.g., BMI 40 or above), or who are pregnant. Further work-up will depend on the type and severity of the abnormality. Mixing studies of PT and/or aPTT are commonly used to determine quantitative factor deficiency (if mixing studies correct prolonged PT/aPTT) or the presence of inhibitors (if mixing studies do not correct prolonged PT/aPTT). Fibrinogen assay is used for the diagnosis of DIC.

A peripheral blood smear should be ordered in patients with an abnormal FBC result to exclude abnormal cell morphology (e.g., leukaemia or lymphoma) or schistocytes (e.g., TTP, HUS, or DIC). Some congenital platelet disorders are associated with macrothrombocytopenia (e.g., Bernard-Soulier disease, MYH9-related disorders) or small platelet size (e.g., Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome). ADAMTS-13 antigen level can be used to differentiate HUS from TTP (it is usually normal in HUS).

Factor assays can definitively determine the levels or activities of individual coagulation factors and are crucial in the diagnosis of coagulation factor deficiencies (e.g., haemophilia, vWD). von Willebrand factor (vWF) assays (e.g., vWD antigen and vWD activity assays, including the ristocetin cofactor assay and functional assays) are used for the diagnosis of vWD and to differentiate between the major types of vWD (types I, II, and III).[34] If type II is suspected (i.e., vWF activity/antigen ratio <0.7), vWF multimer assays are needed to differentiate between the different subtypes.[34][35] The platelet function analyser (PFA-100) has replaced bleeding time and is widely offered in laboratories as an easy and inexpensive screening test for the evaluation of bleeding disorders. Its sensitivity and specificity for common bleeding disorders (such as vWD and platelet function disorders) has been reported to be 80% to 90% and 80% to 87%, respectively.[36][37] However, there are ongoing debates regarding the practicality of this test. Given its suboptimal sensitivity, it is well accepted that a normal PFA-100 result should not preclude further work-up for vWD or platelet dysfunction with more specialised testing. A Bethesda assay should be ordered if there is a strong suspicion of acquired coagulation inhibitors. Bleeding time is generally not used in the US given its suboptimal sensitivity and specificity; however, it may still be used in other countries.

More specialised platelet laboratory tests, including platelet aggregation tests, platelet electron microscopy testing, and platelet ATP release assay by flow cytometry, can further determine the functionality and anatomy of platelets and can aid diagnosis of platelet-release defects and/or platelet storage pool disorders. However, these specialised tests are often only offered at selected tertiary centre laboratories.

A baseline metabolic panel and tests of renal and hepatic function are recommended. Abnormal liver function tests suggest a possible hepatic cause of easy bruising. Bruising related to a medication that undergoes renal clearance is more likely in patients with renal impairment.

Other tests should be directed by the history and exam. If Cushing's syndrome is a possibility, urinary and/or salivary cortisol levels and a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test should be ordered. Blood alcohol or vitamin levels may be required if indicated by history. Genetic testing is recommended for selective genetic conditions, including TAR syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Patients with leukaemia and lymphoma may have elevated blood levels of uric acid and lactate dehydrogenase, reflecting increased turnover of malignant cells and tumour lysis syndrome.

Viral serology (i.e., HIV, hepatitis C) is useful in suspected ITP as specific viral infections can be associated with ITP.[24] The presence of antinuclear antibodies may indicate autoimmune-related ITP. Serum immunoglobulin levels should be ordered if Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome is suspected.

Bone marrow biopsy is recommended when bone marrow disorders (e.g., leukaemia, lymphoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, aplastic anaemia) are suspected. A lymph node biopsy is also recommended when lymphoma is suspected.

Imaging

Imaging tests are generally not useful in the evaluation of easy bruising; however, x-rays or computed tomography (CT) are required in cases of suspected physical abuse and may show bone fractures or intracranial bleeding. Positron emission tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, CT, ultrasound, or skeletal survey may also be ordered if malignancy is suspected.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer