Around 88% to 100% of patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) will develop polyps.[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

Polyp-related symptoms usually arise in childhood and are seen by the age of 10 years in 33% and by 20 years in 50% to 70% of patients.[3]Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010 Jul;59(7):975-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20581245?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Hinds R, Philp C, Hyer W, et al. Complications of childhood Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: implications for pediatric screening. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004 Aug;39(2):219-20.

https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2004/08000/Complications_of_Childhood_Peutz_Jeghers_Syndrome_.27.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15269641?tool=bestpractice.com

Some patients present for a pre-symptomatic evaluation based on family history of the disease.

History and family history

Any history of intestinal polyposis, extra-intestinal polyposis, mucocutaneous pigmentation, or malignancies in the patient and in the family should be noted. Gastric, small bowel, and colorectal polyposis occur in 88% to 100% of patients, with the majority appearing in the small bowel (60% to 90%) and colon (50% to 64%).[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

Polyp growth begins in childhood by age 10 years, with most people experiencing symptoms such as bleeding, abdominal pain, intussusception, or obstruction by age 18 years.[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

Bleeding may be occult or overt and can result in iron-deficiency anaemia and fatigue. Mucocutaneous pigmentation affects >95% of individuals and may often have been present in infancy but fades with time.[8]Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb;110(2):223-62.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2015/02000/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Genetic_Testing_and.8.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25645574?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

PJS is recognisable by the characteristic pigmented macules (flat, blue-grey to brown spots 1 to 5 millimetres in size) which occur most commonly in the perioral region and buccal mucosa (94%). They can also occur on the digits, palms, soles, face, forearms, perianal region, and rarely on the intestinal mucosa.[8]Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb;110(2):223-62.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2015/02000/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Genetic_Testing_and.8.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25645574?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Apr;4(4):408-15.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16616343?tool=bestpractice.com

The macules on the lips are distinctive as they cross the vermillion border and are typically darker and more densely clustered than freckles.[8]Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb;110(2):223-62.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2015/02000/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Genetic_Testing_and.8.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25645574?tool=bestpractice.com

Pigmented macules on the skin increase in intensity from infancy and early childhood and often fade in adult life with complete disappearance in some patients. Accordingly, in adult patients, a lack of cutaneous findings does not exclude PJS. The buccal lesions usually persist.[17]Latchford A, Cohen S, Auth M, et al. Management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children and adolescents: a position paper from the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019 Mar;68(3):442-52.

https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2019/03000/Management_of_Peutz_Jeghers_Syndrome_in_Children.31.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30585892?tool=bestpractice.com

Although uncommon, anaemia may arise as a consequence of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to polyps; pallor, fatigue, and tachycardia may be present.

Males should be examined for signs of testicular tumours, and should be encouraged to perform regular testicular self-examinations. Mildly enlarged testicles (without masses) or features of feminising precocious puberty (for example, bilateral gynaecomastia) may suggest an underlying Sertoli cell tumour. The average age of diagnosis for testicular cancer is aged 9 years, with a range of 3-20 years.[21]Giardiello FM, Bresinger JD, Tersmette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000 Dec;119(6):1447-53.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11113065?tool=bestpractice.com

Occasionally polyp prolapse per anus may be present in both sexes. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic pigmentation present on lips and buccal mucosaFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends].

Diagnostic criteria

A diagnosis of PJS should be considered in a person who satisfies any one of the following:[3]Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010 Jul;59(7):975-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20581245?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1436

Two or more histologically confirmed Peutz-Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyps (PJ-type polyps)

Any number of PJ-type polyps with a family history of PJS in a first-degree relative

Characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation with a family history of PJS

Any number of PJ-type polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation

Individuals who meet the clinical criteria should undergo genetic evaluation.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing should be utilised to confirm the clinical diagnosis in those patients who satisfy the diagnostic criteria for PJS or with a family history of PJS.[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1436

Genetic testing is also recommended for those with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) STK11 variant detected by tumour genomic testing on any tumour type in the absence of germline analysis.[22]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1436

Sequencing of STK11 on chromosome 19p13.3, which encodes for the serine-threonine kinase LKB1, will detect 30% to 69% of mutations, and deletion/duplication analysis will find another 30% of germline alterations.[16]Amos CI, Keitheri-Cheteri MB, Sabripour M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004 May;41(5):327-33.

https://jmg.bmj.com/content/41/5/327.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15121768?tool=bestpractice.com

[23]Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, et al. High proportion of large genomic STK11 deletions in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2005 Dec;26(6):513-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16287113?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Volikos E, Robinson J, Aittomaki K, et al. LKB1 exonic and whole gene deletions are a common cause of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006 May;43(5):e18.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2564523

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16648371?tool=bestpractice.com

The large majority of genetic testing for inherited cancer risk predisposition is performed using multigene panel testing.[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

A positive result confirms the diagnosis. Small and large deletions, insertions, splice site, and missense mutations in the STK11 gene have all been reported.[6]Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Genet. 1998 Jan;18(1):38-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9425897?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Hemminki A, Makie D, Tomlinson I, et al. A serine threonine kinase gene defect in Peutz Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998 Jan 8;391(6663):184-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9428765?tool=bestpractice.com

A negative result significantly reduces the likelihood that the patient has PJS, although variant mutations may be missed. A variant of uncertain significance (VUS) could also be identified.

If an individual meets the clinical diagnostic criteria for PJS but has a negative or VUS result on genetic testing, they should be managed as though they have PJS or evaluated further for another genetic syndrome.[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

Once a mutation is identified in a proband, at-risk family members can be tested for this family-specific alteration. It should be recognised that, while most patients will have an affected parent, approximately 25% of patients have de novo mutations.[8]Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Feb;110(2):223-62.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2015/02000/ACG_Clinical_Guideline__Genetic_Testing_and.8.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25645574?tool=bestpractice.com

Even if the mutation is thought to be de novo, the first-degree relatives of patients with PJS should be carefully evaluated for features of PJS (gastrointestinal polyps or mucocutaneous pigmentation), and they should be offered genetic testing.

Whether inherited or de novo, all children of the proband have a 50% risk of inheriting the mutation and should be offered genetic testing. After appropriate genetic counselling and informed consent, testing for any at-risk family members should be performed. Given the paediatric manifestations of PJS, genetic testing of at-risk children should not be delayed until adulthood.

Gene reviews: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Opens in new window

Endoscopic evaluation

Endoscopic evaluation is indicated for three groups of individuals:

Asymptomatic individuals with PJS undergoing surveillance.

Symptomatic individuals or patients with laboratory or radiographic abnormalities suggestive of PJS.

At-risk first-degree relatives who meet the phenotypic criteria (i.e., colonic polyps or mucocutaneous pigmentation) when the family mutation is not identified.

Surveillance of the colon, stomach, and duodenum by oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and colonoscopy should begin by age 8 years in affected asymptomatic individuals (and earlier in those with symptoms).[17]Latchford A, Cohen S, Auth M, et al. Management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children and adolescents: a position paper from the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019 Mar;68(3):442-52.

https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2019/03000/Management_of_Peutz_Jeghers_Syndrome_in_Children.31.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30585892?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1436

[25]Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut. 2020 Mar;69(3):411-44.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/69/3/411.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31780574?tool=bestpractice.com

Small bowel surveillance with video capsule endoscopy (VCE) or computed tomography/magnetic resonance enterography (CTE or MRE) should also begin by aged 8 years (and earlier if the patient is symptomatic).[3]Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010 Jul;59(7):975-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20581245?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Latchford A, Cohen S, Auth M, et al. Management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children and adolescents: a position paper from the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019 Mar;68(3):442-52.

https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2019/03000/Management_of_Peutz_Jeghers_Syndrome_in_Children.31.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30585892?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, endometrial, and gastric [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1436

[25]Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut. 2020 Mar;69(3):411-44.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/69/3/411.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31780574?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]van Leerdam ME, Roos VH, van Hooft JE, et al. Endoscopic management of polyposis syndromes: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019 Sep;51(9):877-95.

https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/a-0965-0605

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31342472?tool=bestpractice.com

Capsule endoscopy is safe to use in individuals with PJS and small bowel polyposis who lack obstructive symptoms. If a concern for capsule retention is present, a patency capsule should be utilised. In general, adverse events associated with diagnostic EGD are rare (reported rates: infection <0.3%, bleeding <0.1%, cardiopulmonary events <0.1%, perforation <0.01%).[27]ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Coelho-Prabhu N, Forbes N, et al. Adverse events associated with EGD and EGD-related techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Sep;96(3):389-401.e1.

https://www.giejournal.org/article/S0016-5107(22)00337-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35843754?tool=bestpractice.com

The most common endoscopic finding is diffuse hamartomatous polyposis. Gastric, small bowel, and colorectal polyposis occur in 88% to 100% of patients, with the majority appearing in the small bowel (60% to 90%) and colon (50% to 64%).[18]Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, et al. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jun;162(7):2063-85.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(22)00151-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35487791?tool=bestpractice.com

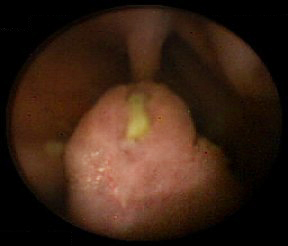

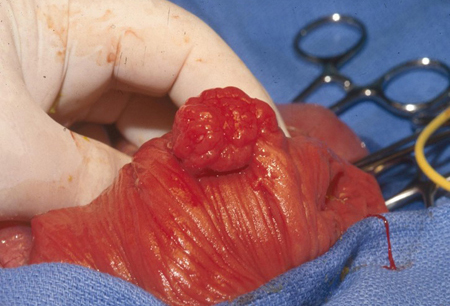

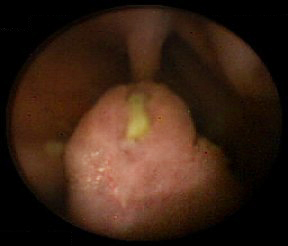

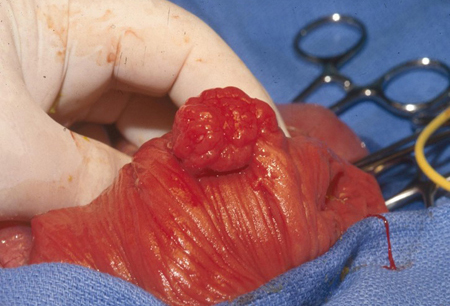

In rare cases, polyps have also occurred in the renal pelvis, urinary bladder, lungs, and nares. Polyps may be small or large, sessile, or pedunculated. They often have a characteristic cerebriform appearance due to smooth muscle arborisation within the polyps. Multiple polyps are typical; usually the total number is below 20. Individual polyps vary in size from a few millimetres to several centimetres. Pathologically the polyp is hamartomatous in nature; smooth muscle core is covered by lamina propria and mature glandular epithelium. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Small bowel hamartomatous polyp identified on capsule endoscopyFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polypoid mass in the small bowelFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polypoid mass in the small bowelFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic serosal dimpling resulting from a pedunculated hamartoma in the small bowel of a patient with PJSFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends].

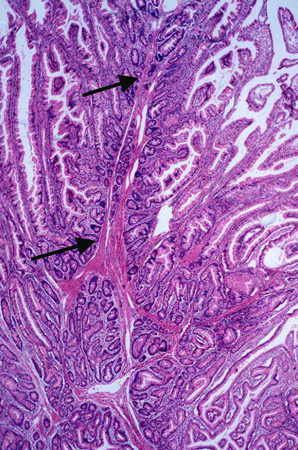

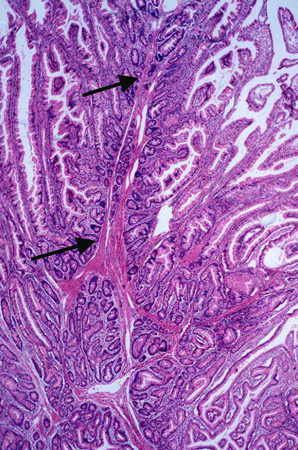

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic serosal dimpling resulting from a pedunculated hamartoma in the small bowel of a patient with PJSFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histology of a hamartomatous polypFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histology of a hamartomatous polypFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polypoid mass in the small bowelFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Polypoid mass in the small bowelFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic serosal dimpling resulting from a pedunculated hamartoma in the small bowel of a patient with PJSFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Characteristic serosal dimpling resulting from a pedunculated hamartoma in the small bowel of a patient with PJSFrom the collection of Dr James Church, used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histology of a hamartomatous polypFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histology of a hamartomatous polypFrom the collection of Dr Carol A. Burke, used with permission [Citation ends].