Details

Worldwide, an estimated 660,000 new cases of cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2022, with approximately 350,000 deaths. WHO: cervical cancer Opens in new window Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in women and ranks second in resource-limited countries.

Cervical cancer is caused primarily by persistent infection of the cervix with human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is a sexually transmitted infection and is common in sexually active individuals. Most infections resolve spontaneously, but persistent infection of the cervix, if untreated, can cause abnormal, precancerous cells to develop. Cervical screening can detect precancerous and cancerous lesions in asymptomatic women.[1][2][3][4][5]

Cervical cancer screening has been hailed as one of the most successful preventative medical strategies. It has been associated with a 70% reduction in cervical cancer mortality in developed countries since the introduction of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test in 1941.[6][7]

Cancer Research UK: Cervical cancer mortality statistics

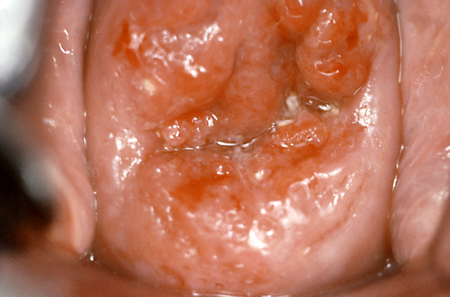

Opens in new window[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Colposcopic view of cervical carcinomaCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Citation ends].

HPV infection of cervical epithelial cells is associated with characteristic morphological changes, and the presence of HPV can, therefore, be indicated by histopathological observation. HPV tests, either alone or with cytology, are a newer method of cervical cancer screening.

Cervical cancer is rare in women under the aged 21 years. Routine screening is recommended for those with a cervix aged 21 years to 65 years. Screening may be clinically indicated in women over the aged 65 years who have not had adequate prior screening or are at high risk of cervical cancer. Women who have undergone total hysterectomy (i.e., their cervix has been removed) no longer need cervical cancer screening, as long as they have no previous history of cervical cancer or dysplasia. Women of any age who have a limited life expectancy can also discontinue cervical cancer screening.[1][3][4][5]

ACOG: cervical cancer screening FAQs Opens in new window

National Cancer Institute: cervical cancer screening Opens in new window

See Cervical cancer

Cervical screening samples cells from the junction of the ectocervix and endocervix (the transformation zone or squamocolumnar junction, where 90% of cervical neoplasias originate) to identify pre-malignant or malignant lesions.[8]

Epidemiological, not randomised, data support the impact of cervical screening. The sequential introduction of screening in Canada, matched neighbourhood controlled studies, and the introduction of screening to Finland, Sweden, and Iceland in the 1960s were associated with a fall in the incidence of cervical cancer.[9][10][11] More than half of cervical cancers diagnosed in the US occur in women who fail to attend screening.[12]

Conventional cytology using fixed cells on a slide sampled by spatula has a reported sensitivity of 30% to 87% for dysplasia.[13] A meta-analysis suggested a sensitivity of 58% when used for population screening.[14][15]

Since the mid-1990s, newer techniques have used a liquid transport medium (liquid-based cytology) based on ethanol to preserve cells. Several commercial products are available. The liquid sample has the advantage of allowing other diagnostic assessments for sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and HPV to triage risk. Additionally, the proportion of unsatisfactory specimens has been reduced from 4.1% to 2.6%.[16] Standard slide cytology and liquid-based cytology have similar diagnostic accuracy, with reported sensitivity of liquid-based cytology ranging from 61% to 66% with a specificity of 80% to 91%.[17][18]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histology of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasiaFrom the collection of Dr Richard Penson, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; used with permission [Citation ends].

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening of average-risk women with cytology (cytological tests without human papillomavirus [HPV] tests) from the aged 21 years, and then once every 3 years, if the results are normal.[1][5] Average-risk women should not be screened for cervical cancer with cytology more often than once every 3 years.[4][5] Average risk is defined as those with no history of a precancerous lesion (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or a more severe lesion) or cervical cancer, those who are not immunocompromised (including being HIV-infected), and those without in utero exposure to diethylstilbestro

Unsatisfactory cytology tests should be repeated in 2-4 months.[2][19] Appropriate follow-up evaluation should be undertaken for women with abnormal cytology, irrespective of HPV testing status.[2][5][19] Screening of average-risk women should stop from the aged 65 years, if they have had three consecutive negative cytology results or two consecutive negative cytology plus HPV test results within 10 years, with the most recent test performed within 5 years.[1][3][4][5]

Classification of test results, based on the Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology, was first introduced in 1988 and revised in 2001 to define satisfactory samples and to standardise reporting.[20] Inadequate samples for evaluation include those tests that lack patient-identifying information, broken slides, inadequate squamous component (defined as <5000 squamous cells on liquid-based medium or <8000 to 12,000 cells on conventional medium), or obscuring elements on over 75% of squamous cells (typically due to lubricant, inflammation, or blood).

The Bethesda System terminology for cytological reporting classifies epithelial abnormalities as follows.[20]

Squamous cell abnormalities

Atypical squamous cells (ASC)

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (ASC-H)

Low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (LSIL), encompasses those previously classified as koilocytic atypia (HPV changes) or cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) 1

High-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (HSIL), encompasses those formerly called CIN 2 or CIN 3

Squamous cell carcinoma.

Glandular cell abnormalities

Atypical glandular cells (AGC)

Atypical glandular cells, favour neoplastic

Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

Adenocarcinoma.

The Bethesda System classifies LSIL and HSIL as squamous cervical precursor lesions.

Although originally used as cytological diagnoses, the squamous intra-epithelial lesion terminology can be used for histological classification as well. Generally, CIN grades 1 to 3 are used to classify histological diagnoses. More than two-thirds of smears showing cellular atypia do not meet diagnostic criteria for dysplasia and are classified as ASC-US or as ASC-H. Studies have shown that up to 90% of LSIL will spontaneously regress.[21][22] However, some estimates suggest that LSIL may carry up to a 33% risk of harbouring a higher-grade lesion (CIN 2 or 3). HSIL carries a risk of >70%.[23][24]

HPV infection has been implicated in over 90% of high-grade cervical dysplasia and nearly 100% of cervical cancers.[25][26] Failure to clear HPV is likely to be a primary factor in the subsequent development of dysplasia. Oncogenic or high-risk subtypes of HPV are 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68.[27] Investigations have shown that HPV-16 and HPV-18 are associated with significantly more high-grade (at least CIN 2) lesions than other high-risk subtypes.[28]

In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved DNA-based testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) types as an option for primary cervical cancer screening in women aged 25 years and older. Because of the high prevalence of HPV infection in women younger than 30 years, and the fact that many infections are fleeting, HPV testing is not routinely recommended in average-risk women younger than 30 years.[4] HPV testing is more useful in older age groups because these women are more likely to have established infection. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening of average-risk women with hrHPV testing alone or in combination with cytology (co-testing) every 5 years from the aged 30 years.[1][5]

Management (return to routine screening, more or less frequent surveillance, colposcopy, or treatment) is determined by clearly defined risk thresholds for CIN 3+ lesions derived from the results of HPV testing, alone or in combination with cytology, and the patient’s past history.[2][19]

Primary hrHPV testing

The US is in a transition period from cytology testing to primary hrHPV testing. The American Cancer Society (ACS) has updated its guidance to recommend women aged 25-65 years should be screened with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years as an alternative to cytology-based screening; if hrHPV testing is unavailable, however, the ACS recommends individuals aged 25-65 years should be screened with co-testing (hrHPV testing in combination with cytology) every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.[3]

In England, the National Health Service (NHS) Cervical Screening Programme offers all women between the aged 25 years and 64 years a free cervical screening test every 3 years to 5 years depending on age. National Health Service: cervical screening programme Opens in new window

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Screening intervalsCreated by BMJ Evidence Centre based on information from the National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme [Citation ends].

The samples are tested for HPV. If the HPV test is negative, the patient returns to regular screening every 3 years to 5 years, depending on age. If HPV is found, liquid-based cytology is used to detect abnormal cell changes. If the cytology result is negative, the patient will be offered screening again at 12 months. If the cytology result is abnormal, the patient will be referred for a colposcopy. Cervical screening: colposcopy and programme management Opens in new window

HPV testing, with or without intermediate triage using visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid, may have a role in resource-poor settings.[29] If HPV testing is unavailable, visual inspection of the cervix after application of dilute acetic acid followed by treatment with cryotherapy is recommended.[29] One Indian study reported a reduction in advanced cervical cancer in women aged more than 30 years compared with those screened with cytology.[30]

HPV self-sampling has the potential to improve access to, and compliance with, cervical cancer screening. The World Health Organization recommends it as an additional approach for individuals aged 30-60 years, but the approach is still investigational in the US.[31]

Co-testing (hrHPV testing and cytology)

In co-testing, cytology and hrHPV testing are administered together from the same sample of cells taken from the cervix.

Reflex testing

Cytology samples that report either ASC-US or LSIL results should be tested for the presence of HPV types associated with CIN (reflex HPV testing or HPV triage). Multiple studies, including the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS), have demonstrated that HPV testing after ASC-US test results are obtained can improve detection of higher-grade lesions.[23][28][32][33] At 10-year follow-up, one study reported finding CIN 3 in 21% and cervical cancer in 18% of women who were initially cytology-negative but HPV-16- or HPV-18-positive. High-grade lesions (CIN 3 and cervical cancer) were identified in only 1.5% of all other cytology-negative, hrHPV-positive women at 10-year follow-up.[28] Positive primary hrHPV tests should have an additional cytology review on the same sample (reflex cytology testing), to classify epithelial abnormalities and inform management.[2][19]

The combination of HPV vaccination and cervical screening provides the greatest protection against developing cancers caused by HPV, including cervical cancer. Following the introduction of the vaccination programme in the US, there has been a reduction in HPV prevalence and cervical precancer incidence.[34][35][36][37] A reduction in HPV-16 and HPV-18-positive CIN 2+ lesions has also been observed in unvaccinated women, which suggests herd protection in these women.[38]

There are three HPV vaccines licensed to prevent HPV infection: bivalent (HPV-16 and HPV-18); quadrivalent (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-18); and 9-valent (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58). In the US, only the 9-valent vaccine is available and approved for use in females and males aged 9-45 years.[39] The quadrivalent vaccine is available in some other countries. A single dose of HPV vaccine is effective in preventing cervical infection with HPV-16 and HPV-18, the two types of HPV that cause 70% of cervical cancers.[40][41][42] Different HPV vaccine types have comparable efficacies and immunogenicity data suggests high levels of persistent antibody titres 10 years after immunisation.[43][44][45]

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends HPV vaccination for all children and adults aged 9-26 years.[46][47][48] The recommended age for vaccination is 11 to 12 years; however, the vaccination series can begin at age 9 years. The ACIP recommendation for HPV vaccination is for a two or three dose series, depending on age at initial vaccination or condition.[46][47][48] Shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV catch-up vaccination is recommended in people aged 27-45 years who were not adequately vaccinated when younger.[47][48]

In the UK, HPV vaccination is recommended in all adolescents aged 12 years and 13 years. Girls are eligible to receive the vaccine up to their 25th birthday and boys born on or after 1 September 2006 are eligible to receive the vaccine up to their 25th birthday.[49] Men who have sex with men up to and including aged 45 years who are attending consultant sexual health clinics and/or HIV clinics are recommended to have the vaccine.[49]

The vaccines are considered to be very safe, with typical side effects including pain, itching, irritation, erythema, and low-grade fever.[50]

Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened following the general population cervical screening recommendations.[5]

Colposcopy provides a magnified view of the cervix and vaginal tissue, which enables normal-appearing tissue to be distinguished from abnormal-appearing tissue. Additionally, it enables directed biopsies to be taken for pathological examination. Reported sensitivity of colposcopy can be as low as 58%, although this may increase with analysis of two or more directed biopsies. Cytological diagnosis and histological diagnosis are directly correlated in 50% of patients. In a study of patients with LSIL, 45% of patients had CIN 1 on biopsy, 16% had CIN 2 or 3, and 33% had normal histology.[51] Findings were similar for HSIL. All visible lesions should be biopsied, with repeated colposcopic examinations to follow persistently abnormal cytology. Treatment is determined by findings on colposcopy and biopsy.[2]

[  ]

]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer