Aetiology

Vehicle accidents are the most common cause of cervical spine injuries. The injury mechanism commonly referred to as a whiplash injury occurs most often in rear-impact collisions, although it can occur in any type of collision.[10] Momentary hyperextension of the spine produces peak rotational forces, most often at the C5-C6 level (although all segments of the cervical spine can be injured), resulting in a unique facet injury mechanism at this level, in which the articulating surface of the upper segment is jammed into that of the lower segment.[11] The unique whiplash injury mechanism results in cervical spine flexion, compression, extension, distraction, and shear, all in less than one fifth of a second.[11]

Falls, especially in older people, and violent assaults are increasingly common mechanisms of cervical spine injury.[4][12]

A dangerous mechanism of injury is a strong risk factor for a cervical spine injury:[13][14]

A fall from a height of greater than 1 metre or 5 steps

An axial load to the head (e.g., diving, high-speed motor vehicle collision, rollover motor accident, ejection from a motor vehicle, accident involving motorised recreational vehicles, bicycle collision, horse riding accidents).

Pathophysiology

Injuries to the cervical spine can involve a variety of tissues: facet joints, discs and disc endplates, and cervical spine ligaments such as the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum. Occasionally a nerve root or the spinal cord will be injured immediately, but more typically inflammatory processes are set in motion by the initial injury. Persistent injury may produce alterations in pain thresholds throughout the body, mediated by pain-processing changes in the spinal cord and brain, a process known as centrally mediated pain or central sensitisation. Muscles may be injured acutely, but may also be a source of pain in chronic cases, as injured muscles can develop trigger points and give rise to myofascial pain syndromes secondarily to other painful injury elsewhere in the spine.[15]

Common fracture patterns

Injury to the cervical spine can be characterised based on:

Location within the spine (e.g., craniocervical junction, atlantoaxial, subaxial)

Forces applied to the spine (e.g., flexion injuries, extension injuries)

Resulting fracture patterns (e.g., facet dislocation, fracture dislocation injury).

Common fracture patterns in the upper cervical spine are:

Occipital condyle fractures

Jefferson's fractures and other atlas (C1) fractures, including fractures of the lateral mass

Atlantoaxial dislocation

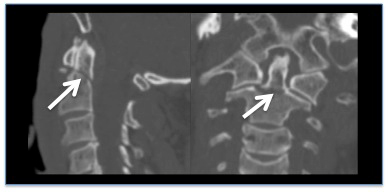

Fractures of C2: hangman fractures (spondylolisthesis of C2), odontoid fractures, lateral body fractures. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT reconstruction demonstrating undisplaced odontoid fractureFrom the personal collection of Michael G. Fehlings [Citation ends].

Common fracture patterns in the lower cervical spine are:

Clay-shoveller's fracture

Simple wedge compression fracture

Bilateral facet dislocation

Flexion teardrop fracture.

Classification

Odontoid dens fracture

The Anderson and D'Alonzo classification links the height of the line through the odontoid process with prognosis:[1]

Type I: fracture of the upper part of the odontoid dens

Type II: fracture at the base of the odontoid dens

Type III: fracture affecting the body of the axis.

Hangman’s fracture

Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis is known as the hangman's fracture.

The Levine and Edwards classification divides traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis into four types:[2]

Type I: fracture without an angular deviation and translational deviation of <3.5 mm, which occurs due to hyperextension and axial compression

Type II: fracture with a significant translational or angular deviation, which occurs due to hyperextension and axial compression combined with a mechanism of flexion-compression

Type IIa: fracture with a small translational deviation and wide angulation, with an increase in posterior disc space between C2-C3 upon application of traction, which occurs due to a flexion-distraction

Type III: fracture with a large translational and angular deviation, which is associated with unilateral or bilateral dislocation of the C2-C3 joint facets and occurs due to a flexion-compression mechanism.

AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system[3]

A morphology-based classification system for clinical and research purposes.The AOSpine subaxial cervical spine injury classification system characterises injury morphology, mechanism of injury, integrity of facets, and neurological status. AOSpine Injury Classification System Opens in new window These criteria (and additional modifiers believed to be important in the management of cervical spine injuries) can be combined using standardised nomenclature to succinctly convey complex information about a patient’s injury pattern.

Lower cervical spine fractures

A classification tool has been derived by expert consensus and validated for intra- and inter-rater reliability.[3] Injuries are assessed by four criteria: (1) morphology, (2) associated facet injury, (3) neurological status, and (4) case-specific modifiers. Morphology is divided into (A) compression injuries, (B) tension-band injuries, and (C) translational injuries. Each category is further subclassified as:

Morphology

Type A - Compression injuries

A0: No bony or minor injury

A1: Single endplate fracture; posterior vertebral wall spared

A2: Both endplates fractured; posterior vertebral wall spared

A3: Single endplate fracture involving posterior vertebral wall

A4: Both endplates fractured involving posterior vertebral wall

Type B - Tension-band injuries

B1: Predominately bony posterior tension-band injury

B2: Complete disruption of posterior capsuloligamentous or bony-capsuloligamentous structures

B3: Anterior tension-band injury

Type C - Translational injuries

C: Displacement or translation of vertebral body relative to another in any direction

Facet injury

F1: Not displaced; fragment <1 cm; <40% lateral mass involved

F2: Displaced or fragment >1 cm or >40% lateral mass involved

F3: Floating lateral mass (complete bony disconnection)

F4: Subluxed/perched/dislocated facet (inferior articular process of rostral vertebra rests on or anterior to superior articular process of caudal vertebra)

Neurology

N0: Intact

N1: Transient deficit completely resolved at time of assessment

N2: Radiculopathy

N3: Incomplete spinal cord injury (spared function below injury)

N4: Complete spinal cord injury (no spared function below injury)

NX: Undetermined

+ Designates ongoing compression

Modifiers

M1: Partial posterior capsuloligamentous injury

M2: Critical disk herniation (extruded nucleus pulposus)

M3: Spine-stiffening disease (i.e., diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, ankylosing spondylitis, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, ossification of the ligamentum flavum)

M4: Vertebral artery injury

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer