Recommendations

Urgent

Strongly suspect bacterial meningitis in adults with all of the following symptoms in the red flag combination:[22]

Fever

Headache

Neck stiffness

Altered level of consciousness or cognition (including confusion or delirium)

Consider bacterial meningitis in adults with any of the above symptoms.[15][23]

Recognise cardiorespiratory arrest, suspected sepsis, meningococcal disease (not covered here), and shock.[15]

These problems take priority over ‘uncomplicated’ bacterial meningitis

Follow local protocols for management

See Sepsis in adults, Meningococcal disease, and Shock.

If you suspect bacterial meningitis, within 1 hour of arrival at hospital:[22]

Arrange initial assessment by senior clinical decision-maker (a clinician with core competencies in the care of acutely ill adult patients - e.g., ST3 level doctor or above in the UK)

Perform a lumbar puncture (unless contraindicated) to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), even if antibiotics have been given in the community[15]

Take blood cultures, even if antibiotics have been given in the community[15]

Assess the need for urgent senior review early using a validated scoring system, such as the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2).[25] Consult local guidelines for the recommended scoring system at your institution.

Seek advice from a senior clinical decision-maker (registrar or consultant) on the initial management of acute bacterial meningitis, as well as a microbiologist or infectious diseases consultant.[15]

Perform a lumbar puncture before starting antibiotics, unless it is not safe to do so or it will cause a clinically significant delay to starting antibiotics.[22]

Delay lumbar puncture, but DO give antibiotics if you suspect bacterial meningitis and the patient has:[15]

Shock

Sepsis or rapidly progressing rash

Severe respiratory or cardiac compromise

Confirmed/known bleeding or high risk of bleeding

Raised intracranial pressure, indicated by:

Reduced or fluctuating level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale of <9 or less or a progressive and sustained or rapid fall in level of consciousness) [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

New focal neurological signs, including seizures or posturing

Abnormal pupillary reactions or papilloedema

In practice, timing of lumbar puncture is a clinical decision. Seek senior advice if you are unsure.

Do not routinely perform neuroimaging before lumbar puncture.[22] Perform cranial imaging before lumbar puncture if there is a risk of cerebral herniation due to conditions such as brain abscess, subdural empyema, or large cerebral infarction.[23][26][27]

This has been a controversial area.[15][28][29] Delaying LP for a computed tomography (CT) scan can cause delays in antibiotic administration, which may lead to an increase in mortality.[30][31]

In practice, most patients will have LP without the need for prior neuroimaging.[15]

The following signs suggest risk of cerebral herniation secondary to raised intracranial pressure:

Papilloedema[15]

Focal neurological deficits (excluding nerve palsies)[15][23]

Altered mental status[15][23] [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Severe immunocompromise[23]

Regardless of decisions about pre-LP neuroimaging, delay or do NOT perform LP in the following situations:[15][23]

Respiratory or cardiac compromise

Signs of severe sepsis or a rapidly evolving rash

Infection at the site of the LP

A coagulopathy

Key Recommendations

Initial assessment

Assess the patient using an ABCDE approach, noting in particular:[15]

Airway – signs of obstruction

Breathing – respiratory rate, oxygen saturation

Circulation – pulse, capillary refill time, urine output, blood pressure

Disability – Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), focal neurological signs, seizures, papilloedema, capillary glucose [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Exposure – petechial or purpuric rash (see Meningococcal disease).

Investigations

As well as taking blood for culture, take blood for:[15][22]

Full blood count

Urea and electrolytes, creatinine, glucose, lactate, coagulation screen, liver function tests

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for pneumococcus and meningococcus

Blood gases

C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or procalcitonin (if available).

Do not rule out bacterial meningitis based only on a normal CRP, PCT, or white blood cell count.[22]

Observe the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample for clues to the diagnosis (see table below) and request the following investigations:[15] [22]

Glucose (at same time as blood glucose taken, so that the cerebrospinal fluid to blood glucose ratio can be calculated)[22]

Protein

Microscopy, culture, and sensitivities

Cell count

Lactate (if prior antibiotics have not been given)

PCR for relevant pathogens (e.g., pneumococcus and meningococcus, enterovirus, herpes simplex varicella zoster, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Classic cerebrospinal fluid features of the different causes of meningitis[15] (reproduced with permission) | |||||

Normal | Bacterial | Viral | Tuberculosis | Fungal | |

Opening pressure (cm CSF) | 12 to 20 | Raised | Normal/mildly raised | Raised | Raised |

Appearance | Clear | Turbid, cloudy, purulent | Clear | Clear or cloudy | Clear or cloudy |

CSF WBC count (cells/uL) | <5 | Raised (typically >100)a | Raised (typically 5 to 1000)a | Raised (typically 5 to 500)a | Raised (typically 5 to 500)a |

Predominant cell type | n/a | Neutrophilsb | Lymphocytesc | Lymphocytesd | Lymphocytes |

CSF protein (g/L) | <0.4 | Raised | Mildly raised | Markedly raised | Raised |

CSF glucose (mmol) | 2.6 to 4.5 | Very low | Normal/slightly low | Very low | Low |

CSF/plasma glucose ratio | >0.66 | Very low | Normal/slightly low | Very low | Low |

Local laboratory ranges for biochemical tests should be consulted and may vary from those quoted here. A traumatic lumbar puncture will affect the results by falsely elevating the white cells due to excessive red cells. A common correction factor used is 1:1000. aOccasionally the CSF WBC count is normal (especially in immunodeficiency or tuberculous meningitis). bMay be lymphocytic if antibiotics given before lumbar puncture (partially treated bacterial meningitis), or with certain bacteria (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes). cMay be neutrophilic in enteroviral meningitis (especially early in disease). dMay be neutrophils early in the course of disease. | |||||

Do not obtain a nasal swab for pneumococcal disease.[15]

Do not order neuroimaging unless you need to detect alternative pathology (e.g., abscess, subdural empyema, or large cerebral infarction) if there are signs of risk of cerebral herniation.[15]

Early recognition is essential. Be aware that bacterial meningitis:[22]

Is a rapidly evolving condition

Can present with non-specific symptoms and signs (without the red flag combination of fever, headache, neck stiffness, and altered level of consciousness or cognition), particularly in older adults

May be difficult to distinguish from other infections with similar symptoms and signs

Symptoms and signs may be more difficult to identify in young adults, who may appear well at presentation

Meningitis and sepsis can occur at the same time, particularly in people with a rash.[22]

The most common features of bacterial meningitis in adults are:[23]

Headache

Present in 87% of adults with bacterial meningitis[16]

Neck stiffness

Fever

Present in 77% of adults with bacterial meningitis[16]

Altered mental status

The classic triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status occurs in only 41% to 51% of patients.[23][33][34] However, in one study, 95% had at least two of the four symptoms of headache, fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status.[16]

Do not exclude the diagnosis of meningitis just because classic symptoms are absent.

Symptoms and signs that may indicate bacterial meningitis in adults.[22]

Symptoms or sign | Further information |

Red flag combination

|

|

Appearance

|

|

Behaviour

|

|

Cardiovascular

|

|

Neurological

|

|

Other

|

Assess the patient using an ABCDE approach, noting in particular:[15]

Airway – signs of obstruction

Breathing – respiratory rate, oxygen saturation

Circulation – pulse, capillary refill time, urine output, blood pressure

Disability – Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, focal neurological signs, seizures, papilloedema, capillary glucose [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Exposure – petechial or purpuric rash (see Meningococcal disease)

Recognise cardiorespiratory arrest, suspected sepsis, meningococcal disease (systemic meningococcal sepsis with or without meningococcal meningitis – not covered here), and shock.[15]

These problems take priority over ‘uncomplicated’ bacterial meningitis

Follow local protocols for management

See Sepsis in adults, Meningococcal disease, and Shock

Practical tip

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[35][36][37]

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST3 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[35][37][38][39]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Practical tip

Meningococcal meningitis cannot be reliably clinically differentiated from bacterial meningitis caused by other bacteria before obtaining Gram stain results.[40]

A petechial rash occurs in 20% to 52% of patients with meningitis and indicates meningococcal infection in more than 90% of these patients.[16]

If the patient has a purpuric or petechial rash, hypotension, and altered mental state with or without symptoms of meningitis, consider meningococcal disease.[15] See Meningococcal disease.

If you suspect non-meningococcal bacterial meningitis, within 1 hour of arrival at hospital:

Assess illness severity using a validated scoring system, such as the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2)[15][36] Consult local guidelines for the recommended scoring system at your institution.

Arrange urgent review by a clinician competent to assess the acutely ill patient if there is an aggregate score of 5/6 (or a score of 3 in any single physiological parameter).

Call the critical care team urgently if the patient has a score of 7 or more.

Do not be falsely reassured if the early warning score is lower than these parameters, because patients with meningitis can deteriorate rapidly.

Seek advice from a senior clinical decision-maker (registrar or consultant) on the initial management of acute bacterial meningitis, as well as a microbiologist or infectious diseases consultant.[15]

Be aware that the sensitivities of Brudzinski's sign and Kernig's sign (classically associated with meningitis) are so low that they are not helpful in diagnosing bacterial meningitis.

More info: Clinical signs of meningism (meningeal irritation)

Kernig’s sign and Brudzinski’s sign are classical signs of meningeal irritation used since the early 20th century to aid the diagnosis of meningitis.[41] Kernig’s sign is the inability to straighten the leg when the hip is flexed to 90°, and Brudzinski’s sign is severe neck stiffness causing the patient’s hips and knees to flex when the neck is flexed.

The 2024 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on recognition, diagnosis and management of bacterial meningitis and meningococcal disease does not recommend checking for Brudzinski's or Kernig’s sign for suspected bacterial meningitis. This is due to their low sensitivity and the difficulty in eliciting these signs, particularly in babies.[22] NICE notes that these signs were introduced at a time when people often presented later (after a few days) and antibiotics did not exist.[22]

The 2016 UK joint specialist societies guideline on the diagnosis and management of acute meningitis and meningococcal sepsis in immunocompetent adults states that Kernig's sign and Brudzinski's sign should not be relied upon for diagnosis of suspected meningitis, noting that sensitivity can be as low as 5%, despite their high specificity (up to 95%).[15]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) is an early warning score produced by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK. It is based on the assessment of six individual parameters, which are assigned a score of between 0 and 3: respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and level of consciousness. There are different scales for oxygen saturation levels based on a patient’s physiological target (with scale 2 being used for patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure). The score is then aggregated to give a final total score; the higher the score, the higher the risk of clinical deteriorationReproduced from: Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London: RCP, 2017. [Citation ends].

Practical tip

Tuberculous meningitis is a medical emergency, but diagnosis can be challenging. Early recognition and prompt treatment improve survival.[42][43] Features include:

1 to 2 weeks prodrome with low-grade fever, malaise, weight loss, and gradual onset of headache

Progresses to worsening headache, vomiting, confusion, and coma

Neck stiffness

III, IV, and VI cranial nerve palsies

Urinary retention

Focal neurological signs such as monoplegia, hemiplegia, and paraplegia

About 50% of patients with bacterial meningitis have predisposing conditions, so ask about risk factors including the following.

Advanced age

Older people are more commonly affected because of impaired or waning immunity.[2]

Crowding

Ideal for bacterial transmission. Outbreaks have been reported in US college dormitories and in training camps for military recruits.[1]

Exposure to pathogens

Risk of acquiring bacterial meningitis is increased after exposure to infection within the household or close contact with a patient who has meningitis.[1]

Visiting an area with a recent outbreak; consider recent travel abroad.[22]

Ask about a source of infection such as otitis media/sinusitis or contact with a person who has had suspected sepsis.[15]

Missed relevant immunisations, such as meningococcal, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) or pneumococcal vaccines.[22]

Immunocompromising conditions

About 50% of patients with bacterial meningitis have a predisposing condition.

Includes chronic conditions such as diabetes, alcohol misuse, or eculizumab therapy.[15]

One third of patients with predisposing conditions have an immunodeficiency.[16]

Congenital immunodeficiencies, such as complement deficiencies, X-linked agammaglobulinaemia, IgG subclass deficiency, or interleukin 1 receptor-associated kinase 4 deficiency, have been associated with bacterial meningitis.[19][22]

Asplenia or hyposplenia increases the risk of overwhelming bacterial infections with encapsulated bacteria, particularly S pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.[19][22]

HIV infection makes people susceptible to bacterial meningitis, particularly if they develop AIDS.

Malignancy:

Patients with leukaemia and lymphoma are susceptible to bacterial meningitis.[17]

Cranial anatomical defects, ventriculoperitoneal shunt

Cochlear implants

Sickle cell disease

Patients are more likely to get meningitis due to impaired splenic function and impaired complement cascade among other mechanisms.[20]

Contiguous infection

Cerebrospinal fluid leak

Patients with a cerebrospinal fluid leak are at higher risk of bacterial meningitis than the general population.[22]

Check for signs of raised intracranial pressure, including:

Focal neurological signs

May include dilated non-reactive pupil, abnormalities of ocular motility, abnormal visual fields, gaze palsy, arm or leg drift

Abnormal eye movement

Suggests cranial nerve palsy (III, IV, VI)

Papilloedema

An enlarged blind spot may be identified when you examine the visual fields

Facial palsy

Cranial nerve VII may be damaged due to inflammation

Balance problems or hearing impairment

Cranial nerve VIII may be damaged due to inflammation

Note other features of meningitis including:[22]

Vomiting

Confusion

May be the only sign in older people

Photophobia

Well-recognised symptom of bacterial meningitis[15]

Seizures

Petechial or purpuric rash

May be present with any type of bacterial meningitis

Blood tests

Take blood for culture within 1 hour of arrival at hospital and ideally prior to giving antibiotics to identify the causative organism and target treatment accordingly.[15][22]

Taking blood for culture should not delay administration of antibiotics.[15]

Take blood cultures, even if antibiotics have been given in the community.[15] It is good practice to tell the laboratory that the patient has received antibiotics.

Take blood for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for specific bacteria, including meningococcal and pneumococcal.[22]

This is especially important if antibiotics have been given prior to taking blood or performing a lumbar puncture, as PCR will remain positive for several days after antibiotics have been started.[15][46][47]

It is useful in distinguishing bacterial from viral meningitis; false-negative results are uncommon (about 5% of cases).[2]

Patients with severe bacterial meningitis often have metabolic abnormalities.[15] Always request:

Serum glucose - may show hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia[15][22]

Full blood count - may show raised white blood cell count, low red blood cell count, and low platelet count[15][22]

Patients with rapidly progressive infections may initially have a normal white blood cell count

Neutropenia can occur in severe infections

Serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes - may show acidosis, hypokalaemia, hypocalcaemia, and hypomagnesaemia[22]

Low sodium may point towards tuberculous meningitis

Venous blood gas - mainly to measure lactate concentration

Liver function tests - may be raised, showing metabolic abnormalities[15][22]

Coagulation screen - may show evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation such as prolonged thrombin time, elevated fibrin degradation products or D-dimer, or low fibrinogen or antithrombin levels[22]

Seek consent and test all patients with meningitis for HIV as a screen for predisposition to meningitis.[15][22]

HIV infection is associated with a higher incidence of bacterial meningitis and a corresponding higher mortality than in the general population.[15]

Up to 24% of patients with acute HIV seroconversion illness present with meningitis, but HIV antibody tests may be negative in this early phase of the illness.[15][49][50]

Measure C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or serum procalcitonin (PCT) if available:

If the cerebrospinal fluid Gram stain is negative and the differential diagnosis is between bacterial and viral meningitis, a normal serum CRP concentration excludes bacterial meningitis with around 99% certainty.[51]

Serum procalcitonin: this has both sensitivity and specificity of over 90% when used to distinguish between bacterial and viral meningitis.[52][53]

Do not perform procalcitonin testing without an established, evidence-based protocol.[54]

Although PCT may help differentiate bacterial from other inflammatory causes, evidence does not show a large difference in diagnostic accuracy for bacterial meningitis compared to CRP.[15][22]

Cerebrospinal fluid

Do a lumbar puncture (LP) to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within 1 hour of arrival at hospital unless there are indications for neuroimaging or contraindications (see below).[15]

Perform the lumbar puncture before starting antibiotics, unless it is not safe to do so or it will cause a clinically significant delay to starting antibiotics.[22]

In practice, timing of lumbar puncture is a clinical decision. Seek senior advice if you are unsure. The need for a rapid LP has to be weighed against the desire to start antimicrobial treatment urgently.[15]

Carry out LP even if the patient has started antibiotics, preferably within 4 hours of starting treatment.[15]

The culture rate can drop off rapidly after 4 hours, making it difficult to identify the causative organism (but prompt molecular tests will still identify the causative organism even after antibiotics have been started).

At least 15 mL of CSF is required for investigations.[15][24] Inform the lab of an urgent CSF sample, which will need confirmation of receipt and urgent processing.

Biochemical measurements can indicate the likely cause of bacterial meningitis, but are not always definitive. Interpret results within the clinical context.

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Measure opening pressure (if patient is horizontal).[15]

Request the following to be performed on the CSF sample.

CSF microscopy, Gram stain, culture, and sensitivities[15][22]

Gram stain rapidly and accurately identifies the causative bacteria in 60% to 90% of patients with community-acquired meningitis.[61] It has a sensitivity of 50% to 99% and a specificity of 97% to 100%.[15][16] This means that if bacteria are present in the CSF, you can be certain of the diagnosis, but a lack of bacteria on the Gram stain does not exclude the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis.

The likelihood of a positive Gram stain result depends on the specific pathogen: the Gram stain is positive in 90% in cases of pneumococcal meningitis, 70% to 90% in cases of meningococcal meningitis, 50% in cases of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis, and 25% to 35% in Listeria monocytogenes meningitis.[23][62][63]

CSF culture is diagnostic in 70% to 85% of patients.[44] However, even if culture is negative due to antibiotic administration, bacteria may be identifiable in the CSF for up to 48 hours after intravenous antibiotics.[15][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram-stained Streptococcus species bacteriaCDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

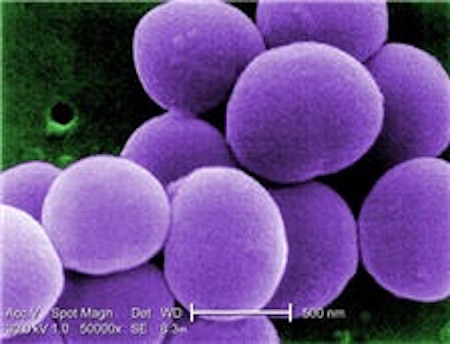

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Staphylococcus aureusCDC/Matthew J. Arduino, DRPH [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Staphylococcus aureusCDC/Matthew J. Arduino, DRPH [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Escherichia coliCDC/Janice Haney Carr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Escherichia coliCDC/Janice Haney Carr [Citation ends].

CSF red and white cell count[22]

CSF biochemistry

Bacterial meningitis tends to have a higher CSF protein than viral meningitis.[65]

CSF glucose[15]

The CSF glucose is low in bacterial meningitis, but the concentration is affected by the concomitant plasma glucose.[66] Therefore, blood glucose should be checked at the same time as the LP to allow interpretation of the CSF glucose.[22] Normally CSF glucose is about two-thirds of the plasma glucose.[15] A CSF glucose concentration of <2.5 mmol/L (<45 mg/dL) or <40% of simultaneously measured serum glucose in bacterial meningitis is likely to indicate a bacterial meningitis.[16]

CSF lactate[15]

CSF PCR for pneumococcus (and meningococcus - see Meningococcal disease)[15][22]

PCR is useful in distinguishing bacterial from viral meningitis.

It is helpful in diagnosing bacterial meningitis in patients who have been pre-treated with antibiotics.[46]

CSF PCR has been reported to have a sensitivity of 79% to 100% for Streptococcus pneumoniae, and 67% to 100% for H influenzae.[23][27]

The value of L monocytogenes PCR is currently unclear.[23][27]

About 5% to 26% of cases of meningitis are caused by bacteria other than S pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, or H influenzae and are not routinely detected by PCR.[23][27]

CSF PCR for tuberculosis (TB) if you have a high clinical suspicion for TB meningitis.[15]

Evidence: CSF lactate

CSF lactate differentiates bacterial from viral meningitis more accurately than CSF glucose, CSF/plasma glucose ratio, CSF protein, or CSF total number of leukocytes. If measured prior to starting antibiotics, CSF lactate has a high negative predictive value to rule out bacterial meningitis and provides reassurance to stop or withhold antibiotics.

One meta-analysis of 25 studies performed in 16 countries and including 783 patients with bacterial meningitis and 909 patients with viral meningitis found that CSF lactate had excellent accuracy in predicting bacterial meningitis. In a head-to-head meta-analysis of these 25 studies, the diagnostic accuracy of the CSF lactate concentration cut-off of >35 mg/dL was higher than that of CSF glucose, CSF/plasma glucose ratio, CSF protein, or CSF total number of leukocytes.[67]

A second meta-analysis included 33 studies. The pooled test characteristics of CSF lactate were sensitivity 0.93 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.96), specificity 0.96 (95% CI 0.93 to 0.98), likelihood ratio positive 22.9 (95% CI 12.6 to 41.9), likelihood ratio negative 0.07 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.12), and diagnostic odds ratio 313 (95% CI 141 to 698), and suggested a CSF lactate of 35 mg/dL could be the optimal cut-off value for distinguishing bacterial meningitis from aseptic meningitis. The sensitivity of CSF lactate concentration was reduced by about 50% in patients who received antibiotic treatment before lumbar puncture, compared with those not receiving antibiotic pre-treatment.[68]

Classic cerebrospinal fluid features of the different causes of meningitis[15] (reproduced with permission) | |||||

Normal | Bacterial | Viral | Tuberculosis | Fungal | |

Opening pressure (cm CSF) | 12 to 20 | Raised | Normal/mildly raised | Raised | Raised |

Appearance | Clear | Turbid, cloudy, purulent | Clear | Clear or cloudy | Clear or cloudy |

CSF WBC count (cells/uL) | <5 | Raised (typically >100)a | Raised (typically 5 to 1000)a | Raised (typically 5 to 500)a | Raised (typically 5 to 500)a |

Predominant cell type | n/a | Neutrophilsb | Lymphocytesc | Lymphocytesd | Lymphocytes |

CSF protein (g/L) | <0.4 | Raised | Mildly raised | Markedly raised | Raised |

CSF glucose (mmol) | 2.6 to 4.5 | Very low | Normal/slightly low | Very low | Low |

CSF/plasma glucose ratio | >0.66 | Very low | Normal/slightly low | Very low | Low |

Local laboratory ranges for biochemical tests should be consulted and may vary from those quoted here. A traumatic lumbar puncture will affect the results by falsely elevating the white cells due to excessive red cells. A common correction factor used is 1:1000. aOccasionally the CSF WBC count is normal (especially in immunodeficiency or tuberculous meningitis). bMay be lymphocytic if antibiotics given before lumbar puncture (partially treated bacterial meningitis), or with certain bacteria (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes). cMay be neutrophilic in enteroviral meningitis (especially early in disease). dMay be neutrophils early in the course of disease. | |||||

Do not perform lumbar puncture if there is:[22]

Extensive or rapidly spreading purpura

Infection at the lumbar puncture site[15]

Risk factors for an evolving space-occupying lesion

Any of the following symptoms or signs of raised intracranial pressure, such as:

Focal neurological signs (including seizures or posturing)

Abnormal pupillary reactions or papilloedema[15]

A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 9 or less, or a progressive and sustained or rapid fall in level of consciousness [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Delay lumbar puncture but DO give antibiotics if you suspect bacterial meningitis and the patient has any of the following relative contraindications:[15]

Shock[22]

Suspected sepsis

Severe respiratory or cardiac compromise

Confirmed/known bleeding or high risk of bleeding[22]

Review the decision to delay lumbar puncture at 12 hours and regularly thereafter.[15]

Debate: Glasgow coma scale (GCS) thresholds for neuroimaging prior to lumbar puncture

Guidelines acknowledge the uncertainty remaining about the ideal GCS score to indicate a requirement for neuroimaging prior to lumbar puncture.

The exact GCS score recommended by guidelines to indicate the requirement for a computed tomographic scan prior to lumbar puncture varies.

Some guidelines are non-specific, stating ‘abnormal level of consciousness’.[70] This means obtunded/not alert or unresponsive.[26]

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends prior neuroimaging if the GCS score is 9 or less, or there is a progressive and sustained or rapid fall in level of consciousness.[22]

The UK joint specialist societies guideline recommends that a lumbar puncture can be performed without prior neuroimaging if the GCS score is >12, and may be safe at lower levels.[71][72] The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases guideline recommends neuroimaging if the GCS score is <10.[23]

A decision about whether to obtain neuroimaging prior to lumbar puncture will depend on your local protocols and resources, as well as the clinical picture in individual patients.

Wait 4 hours after the lumbar puncture before starting prophylactic subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin should an individual patient require anticoagulation.

Be aware that specific recommendations exist for lumbar puncture in patients on anticoagulants.[15] UK joint specialist societies guideline: when should a lumbar puncture be performed in patients who are on anticoagulants? Opens in new window

Cranial computed tomography

Do not routinely perform neuroimaging before lumbar puncture.

Only perform cranial imaging before lumbar puncture if there are:[22]

risk factors for an evolving space-occupying lesion or

any of these symptoms or signs, which might indicate raised intracranial pressure:

New focal neurological features (including seizures or posturing)

Abnormal pupillary reactions or papilloedema[15]

A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 9 or less, or a progressive and sustained or rapid fall in level of consciousness

These clinical features indicate a risk of cerebral herniation due to conditions such as brain abscess, subdural empyema, or large cerebral infarction.[23][26][27]

This has been a controversial area.[15][28][29] Delaying LP for a CT scan can cause delays in antibiotic administration, which may lead to an increase in mortality.[30][31] NICE recommends taking bloods, giving antibiotics and stabilising the patient before imaging.[22]

In practice, most patients will have LP without the need for prior neuroimaging.[15]

Regardless of decisions about pre-LP neuroimaging, delay or do NOT perform LP in the following situations:[15][22][23]

Extensive or rapidly spreading purpura

Infection at the lumbar puncture site

Respiratory or cardiac compromise

Signs of severe sepsis

A coagulopathy

Specific GCS levels indicating a need to delay lumbar puncture or to obtain cranial imaging have been debated. Seek senior advice if you are uncertain about either of these situations.

Computed tomography (CT) scan may identify a tumour, a brain abscess, or meningitis-associated complications such as brain infarction, generalised cerebral oedema, or hydrocephalus.[23][73]

CT scan will not pick up raised intracranial pressure per se.

Neuroimaging is not indicated unless you suspect alternative pathology (i.e., because there are signs indicating risk of cerebral herniation).[15]

In practice, magnetic resonance imaging should be done only if pathology is suspected that is not evident on CT.

More info: Timing of cranial imaging in relation to lumbar puncture

This has been a controversial area.[28][29] A review of the evidence in 2024 resulted in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommending against routinely performing neuroimaging before lumbar puncture.[22]

Delaying lumbar puncture for a CT scan can cause delays in antibiotic administration, which may lead to an increase in mortality.[22][30][31]

Lumbar puncture without prior CT is also associated with lower rates of neurological and/or hearing deficits and functional impairment, and a shorter time to antibiotic treatment (with or without corticosteroids), relative to lumbar puncture after CT.[22]

If neuroimaging shows no signs of risk of cerebral herniation, perform a lumbar puncture as soon as possible unless:[15]

An alternative diagnosis is established

The patient has:

Repeated seizures

Deteriorating GCS [ Glasgow Coma Scale Opens in new window ]

Severe cardiac/respiratory compromise

Other microbiological tests

Do not obtain a nasal swab for pneumococcal disease.[15]

It is not clear whether nasal strains are definitely related to that which caused the meningitis.

Additional tests for viral meningitis

In the UK, the commonest viral causes of meningitis are enteroviruses and herpes viruses.[15] If tests are negative for bacterial aetiology but you still suspect meningitis, confirm the diagnosis with:[15]

CSF, stool, and throat swab PCR for enterovirus

CSF PCR for herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2 and varicella zoster virus

How to perform a diagnostic lumbar puncture in adults. Includes a discussion of patient positioning, choice of needle, and measurement of opening and closing pressure.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer