Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Prioritise resuscitation in line with standard ABC practice. Request an urgent critical care review for any patient with ongoing haemodynamic instability despite adequate resuscitative efforts. Consider activating major haemorrhage protocols early.[34][36][57]

Before diagnostic endoscopy consider intubating the patient if needed (e.g.,if there is haematemesis, or there is a perceived risk of a haemodynamically unstable patient having blood in the stomach, or if the patient presents with an altered mental status). Make sure the patient is appropriately resuscitated before undergoing diagnostic endoscopy.

Follow your local protocols for the pre-endoscopy care of patients with active non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Consider anti-emetics to control nausea and vomiting.

Once the haemorrhage is confirmed by endoscopy, refer the patient to a gastroenterology service for endoscopic treatment.[34][36]

The main goals of initial treatment are to:

Control the bleeding and prevent complications

Eliminate the underlying cause where possible

Identify patients at risk of rebleeding or those who need to be admitted to hospital for further treatment.

Prioritise resuscitation in line with standard ABC practice; protect the airway to prevent aspiration and obtain peripheral venous access. Follow your local protocol.

Give intravenous fluids to all patients.[34]

Monitor the patient using a validated early warning score (e.g., National Early Warning Score 2 [NEWS2]) and use clinical review to determine the infusion rate for your patient.[34] NEWS2 Opens in new window

Guidelines from the National Institute for Care and Health Excellence (NICE) in the UK and a consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding led by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) recommend using a crystalloid solution as a bolus of 500 mL in less than 15 minutes in haemodynamically unstable patients.[34][58] The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines recommend prompt intravascular volume replacement using crystalloid fluids in haemodynamically unstable patients.[35]

Check local protocols for specific recommendations on fluid choice. There is debate, based on conflicting evidence, on whether there is a benefit in using normal saline or balanced crystalloid in critically ill patients.

Practical tip

Be aware that large volumes of normal saline as the sole fluid for resuscitation may lead to hyperchloraemic acidosis. Also note that use of lactate-containing fluid in a patient with impaired liver metabolism may lead to a spuriously elevated lactate level, so results need to be interpreted with other markers of volume status.

Evidence: Choice of fluids

Evidence from a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) suggests there is no difference between normal saline and a balanced crystalloid for critically ill patients in mortality at 90 days, although results from two meta-analyses including these RCTs point to a possible small benefit of balanced solutions compared with normal saline.

There has been extensive debate over the choice between normal saline (an unbalanced crystalloid) versus a balanced crystalloid (such as Hartmann’s solution [also known as Ringer’s lactate] or Plasma-Lyte®). Clinical practice varies widely, so you should check local protocols.

In 2021 to 2022, two large double blind RCTs were published assessing intravenous fluid resuscitation in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with a balanced crystalloid solution (Plasma-Lyte) versus normal saline: the Plasma-Lyte 148 versus Saline (PLUS) trial (53 ICUs in Australia and New Zealand; N= 5037) and the Balanced Solutions in Intensive Care Study (BaSICS) trial (75 ICUs in Brazil; N=11,052).[59][60]

In the PLUS study 45.2% of patients were admitted to ICU directly from surgery (emergency or elective), 42.3% had sepsis and 79.0% were receiving mechanical ventilation at the time of randomisation.

In BaSICS almost half the patients (48.4%) were admitted to ICU after elective surgery and around 68.0% had some form of fluid resuscitation before being randomised.

Both found no difference in 90-day mortality overall or in prespecified subgroups for patients with acute kidney injury (AKI), sepsis or post-surgery. They also found no difference in the risk of AKI.

In BaSICS, for patients with traumatic brain injury, there was a small decrease in 90-day mortality with normal saline - however, the overall number of patients was small (<5% of total included in the study) so there is some uncertainty about this result. Patients with traumatic brain injury were excluded from PLUS as the authors felt these patients should be receiving saline or a solution of similar tonicity.

One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs (including PLUS and BaSICS) confirmed no overall difference, although the authors did highlight a non-significant trend towards a benefit of balanced solutions for risk of death.[61][Evidence A]

One subsequent individual patient data meta-analysis included six RCTs of which only PLUS and BaSICS were assessed as being at low risk of bias. There was no statistically significant difference in in-hospital mortality (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.02). However, the authors argued that using a Bayesian analysis there was a high probability that balanced solutions reduced in-hospital mortality, although they acknowledged that the absolute risk reduction was small.[62]

A pre-specified subgroup analysis of patients with traumatic brain injury (N=1961) found that balanced solutions increased the risk of in-hospital mortality compared with normal saline (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.82).

Previous evidence has been mixed.

One 2015 double-blind, cluster randomised, double-crossover trial conducted in four ICUs in New Zealand (N=2278), the 0.9% Saline vs Plasma-Lyte for ICU fluid Therapy (SPLIT) trial, found no difference for in-hospital mortality, AKI, or use of renal-replacement therapy.[63]

However, one 2018 US multi-centre unblinded cluster-randomised trial - the isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal events Trial (SMART), among 15,802 critically ill adults receiving ICU care - found possible small benefits from balanced crystalloid (Ringer’s lactate or Plasma-Lyte) compared with normal saline. The 30-day outcomes showed a non-significant reduced mortality in the balanced crystalloid group versus the normal saline group (10.3% vs 11.1%; OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.01) and a major adverse kidney event rate of 14.3% versus 15.4% respectively (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.99).[64]

One 2019 Cochrane review included 21 RCTs (N=20,213) assessing balanced crystalloids versus normal saline for resuscitation or maintenance in a critical care setting.[65]

The three largest RCTs in the Cochrane review (including SMART and SPLIT) all examined fluid resuscitation in adults and made up 94.2% of participants (N=19,054).

There was no difference in in‐hospital mortality (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01; High quality evidence as assessed by GRADE), acute renal injury (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.00; GRADE low), or organ system dysfunction (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.61; GRADE very low).

Haemodynamically unstable patients

Request an urgent critical care review for any patient with ongoing haemodynamic instability despite adequate resuscitative efforts. Consider activating major haemorrhage protocols early.[34][36][38]

Base decisions on blood transfusion on the full clinical picture; bear in mind that overtransfusion may be as damaging as under-transfusion.[36]

The BSG consensus care bundle recommends to consider a higher trigger for transfusion than Hb <70 g/L in patients with ischaemic heart disease or haemodynamic instability.[34]

Give platelet transfusion to patients who are actively bleeding and have a platelet count of <50 × 10 9/L.[34][36]

Give fresh frozen plasma if the patient is actively bleeding and has a prothrombin time (or international normalised ratio) or activated partial thromboplastin time >1.5 times normal.[36]

Give cryoprecipitate if the patient has a fibrinogen level that remains <1.5 g/L despite fresh frozen plasma.[36]

Practical tip

Before diagnostic endoscopy consider intubating the patient if needed (e.g., if there is haematemesis, or there is a perceived risk of a haemodynamically unstable patient having blood in the stomach, or if the patient presents with an altered mental status). Make sure the patient is appropriately resuscitated before undergoing diagnostic endoscopy.

The routine use of tranexamic acid in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is not recommended.[35] Studies have shown that high-dose tranexamic acid does not reduce mortality in these patients.[66][67][68]

The ESGE does not recommend the use of tranexamic acid in patients with acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.[35] The ESGE based this recommendation on HALT-IT, an international multicentre randomised controlled trial. The study found that tranexamic acid did not reduce death from gastrointestinal bleeding, compared with placebo. Tranexamic acid was associated with a higher number of venous thromboembolic events.[68]

Haemodynamically stable patients

The BSH and the BSG consensus care bundle recommends following a restrictive transfusion protocol (trigger: Hb <70 g/L; target: 70-100 g/L) in haemodynamically stable patients.[34][57]

Do not offer platelet transfusion if the patient is haemodynamically stable and not actively bleeding.[36]

Patients taking anticoagulation therapy (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs])

Consider seeking advice from an appropriate specialist if the patient is taking warfarin or a DOAC.

The BSG consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding recommends suspending DOACs at presentation and seeking advice from an haematologist when managing patients with severe haemorrhage to weigh up the risks and benefits of the DOAC.[34]

In patients with haemodynamic instability who take a DOAC, the BSG suggests considering the use of reversal agents: idarucizumab in patients taking dabigatran, recombinant coagulation factor Xa (andexanet alfa) in patients taking factor Xa inhibitors (note: it is only licensed in patients treated with apixaban or rivaroxaban), or intravenous four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate if andexanet alfa is not available.[69] Check local protocols for specific recommendations on reversal of DOACs.

The BSG care bundle recommends suspending warfarin at presentation but stresses the importance of ensuring a plan is in place for restarting it. Consult a specialist to discuss the risks associated with stopping warfarin and the need for monitoring.[34]

In patients with haemodynamic instability who take a vitamin K antagonist (usually warfarin), the BSG recommends administering intravenous vitamin K and four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate if prothrombin complex concentrate is not available.[69]

Note that the NICE in the UK recommends:[36]

Prothrombin complex concentrate in patients who are taking warfarin and actively bleeding

Following local warfarin protocols to treat patients who are taking warfarin and whose upper gastrointestinal bleeding has stopped

Recombinant factor Vlla (eptacog alfa) when all other methods have failed.

If any medications are temporarily stopped, also seek advice on the appropriate time for these to be restarted. The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommends restarting anticoagulation:[69]

As soon as possible after 7 days of anticoagulant interruption in patients with low thrombotic risk

Preferably within 3 days of anticoagulant interruption in patients with high thrombotic risk, with heparin bridging.

Patients taking aspirin, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or dual antiplatelet therapy

If the patient is taking aspirin, other NSAIDs (including cyclo-oxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), or dual antiplatelet therapy:

In general, continue aspirin in the acute phase, if your patient is taking this for secondary prevention.[34][35][36][69][70]

Consider seeking urgent advice from a specialist if there is major haemorrhage.

NICE does not make a specific recommendation about major haemorrhage, but advises continuing aspirin only once haemostasis has been achieved.[36]

The BSG consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommend continuing aspirin if this is taken as part of dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), and the P2Y12 is temporarily stopped.[34][69]

The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline recommends that, if aspirin is stopped, it should be restarted as soon as haemostasis is achieved or there is no further evidence of haemorrhage.[69]

The BSG care bundle cites two studies that demonstrate a threefold increase in the risk of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events if aspirin, prescribed for the secondary prevention, is discontinued.[34][70][71][72]

The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline recommends considering permanently discontinuing aspirin if the patient is taking it for primary prevention.[69]

If the patient is taking any other NSAIDs (including COX-2 inhibitors), NICE recommends stopping these during the acute phase.[36]

If the patient is taking dual antiplatelet therapy, seek advice from the appropriate specialist to weigh up the benefits and risks of continuing the P2Y12 inhibitor. Discuss the balance of benefits versus risk with your patient. In general, if the patient:[34]

Does not have coronary artery stents, the P2Y12 inhibitor should be stopped temporarily until haemostasis is achieved

Does have coronary artery stents, dual antiplatelet therapy should ideally be continued due to the high risk of stent thrombosis. However, the risks and benefits of doing so need to be carefully considered by a specialist.

Follow your local protocols for the pre-endoscopy care of patients with active non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

In practice, consider giving an anti-emetic (e.g., cyclizine, promethazine, ondansetron, prochlorperazine) for nausea and vomiting, which may be a cause or an aggravating factor in patients with MWT.

Prokinetics, although not routinely used in UK practice, may improve gastric mucosa visualisation during diagnostic endoscopy by inducing gastric emptying; high-quality evidence supports the use of intravenous erythromycin in particular.[73] The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends pre-endoscopy administration of erythromycin in selected patients with clinically severe or ongoing active upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The ESGE acknowledges that there are difficulties accessing erythromycin in many countries and warns of contraindications to be aware of.[35]

Do not give proton-pump inhibitors pre-endoscopy. This is in line with recommendations from National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines and a consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding led by the British Society of Gastroenterology.[34][36] NICE does not recommend the use of H2 antagonists before endoscopy.[36]

Following the risk assessment, if Glasgow-Blatchford score ≤1, consider managing the patient as an outpatient if safe and appropriate to do so. This approach is supported by latest evidence and in line with recommendations from European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines and a consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding led by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG).[34][35] See Risk stratification under Diagnosis recommendations.

Refer all patients with suspected acute upper GI bleeding for upper GI endoscopy (i.e., gastroscopy).[34][35][36] Follow your local protocol for recommendations on the optimal timing of the procedure for your patient. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the ESGE, and a consensus care bundle led by the BSG, agree that endoscopy should always be performed early (i.e., within 24 hours of presentation) with suspected acute upper GI bleed. However, the exact timing of the procedure within the 24-hour period is controversial and specific recommendations from NICE, the BSG, and the ESGE differ as follows.

The ESGE recommends upper GI endoscopy ≤24 hours from presentation following haemodynamic resuscitation. The ESGE does not recommend urgent (defined by the ESGE as ≤12 hours from presentation) endoscopy.[35]

NICE and the BSG care bundle recommend:[34][36]

Urgent endoscopy, immediately after resuscitation, if the patient is unstable with severe acute upper GI bleeding

Endoscopy within 24 hours of admission for all other patients with upper GI bleeding.

Practical tip

Ensure that haemodynamically unstable patients are adequately resuscitated before undergoing endoscopy.

For more on diagnostic endoscopy, see Imaging under Diagnosis recommendations.

After the endoscopy, review the endoscopy report and instructions from the endoscopist on the ward.[35]

Once the haemorrhage is confirmed by endoscopy, refer the patient to a gastroenterology service for endoscopic treatment.[34][36]

Endoscopic techniques are specialised and should only be undertaken by someone with adequate training and experience.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends using one of the following methods for the endoscopic treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding:[36]

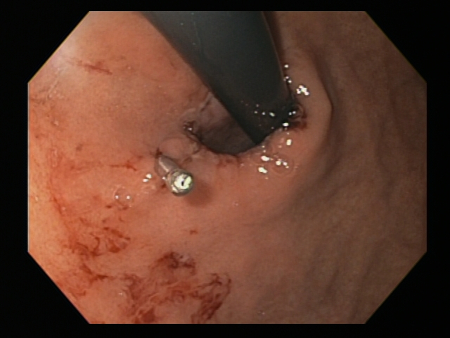

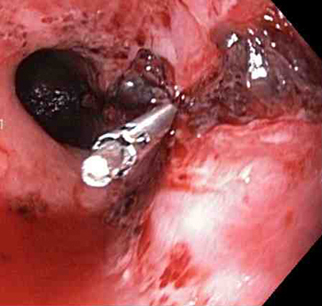

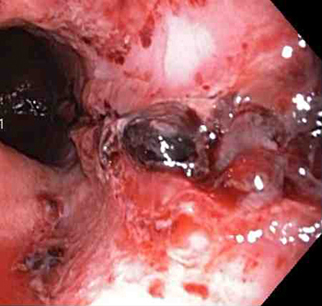

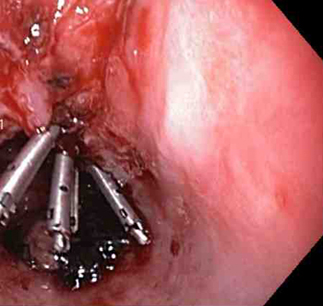

A mechanical method (e.g., clips) with or without adrenaline (epinephrine). In practice, both through-the-scope clips (TTSC) and over-the-scope clips are options depending on availability and expertise. However, for MWT, TTSC usually suffice.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mallory Weiss tear after application of through-the-scope clip results in haemostasisFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission [Citation ends].

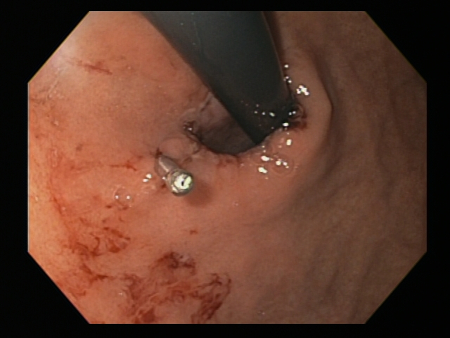

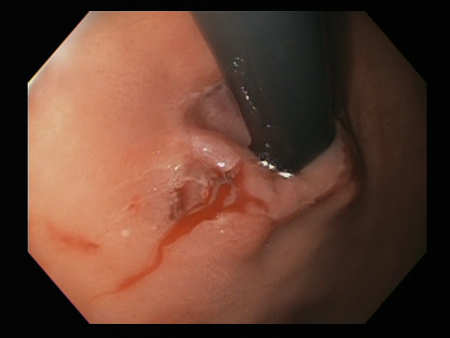

Mallory Weiss tear following cauterisation with a bipolar probe

Mallory Weiss tear following cauterisation with a bipolar probeFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission

Thermal coagulation with adrenaline.

Do not use adrenaline as monotherapy for endoscopic treatment.[36]

More info: Approaches to endoscopic treatment of non-variceal upper GI bleeding

Accepted endoscopic modalities include the following.

Injection therapy

Through-the-scope clips (TTSC), alone or in combination with adrenaline injection to clear the visual field

TTSC are widely available, have a robust evidence base and are usually sufficient to control bleeding in MWT.

TTSC use is as safe and effective as other methods for controlling actively bleeding lesions.[76][77][78][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mallory Weiss tear after application of through-the-scope clip results in haemostasisFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission [Citation ends].

Thermal coagulation

This includes multipolar electrocoagulation or heater probe.

Thermal coagulation is safe and often successful when given by experienced operators.[79][80]

Mallory Weiss tear following cauterisation with a bipolar probeFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission

Mechanical therapy

Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) for MWT has been described in case reports and small randomised controlled trials. The mechanism is similar to that described for variceal band ligation: the affected mucosa is suctioned into the ligating cup device, after which a rubber band is deployed. EBL is simple and safe.[81][82][83] In most cases, EBL is used as a single therapy in which the bleeding point is aspirated and ligated. In practice, EBL is used less commonly in the UK than other forms of mechanical haemostasis, but may be considered as a treatment option in patients with uncontrollable bleeding from MWT.

Cap-mounted, or over-the-scope clips (OTSC) are recommended by the ESGE guidelines in patients with persistent bleeding despite standard endoscopic treatments.[35] Persistent bleeding is defined as ongoing active bleeding refractory to standard haemostasis modalities.[35] The larger OTSCs are less available and not all endoscopists have the expertise to use them.

Topical therapy

A topical hemostatic spray/powder is recommended by the ESGE for patients with persistent bleeding despite standard endoscopic treatments.[35]

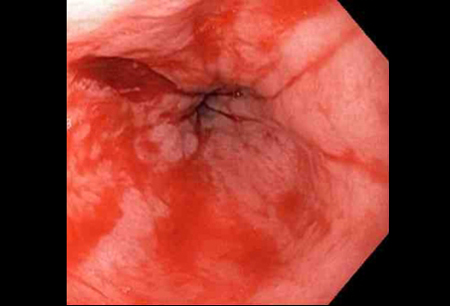

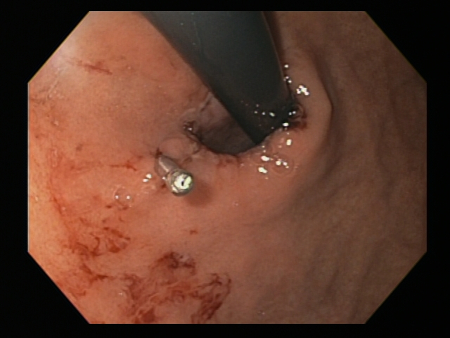

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mallory-Weiss tear after adrenaline injection (the bleeding has stopped, allowing better visualisation of the lesion)From the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adrenaline is injected locally around the site of the Mallory-Weiss tearFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

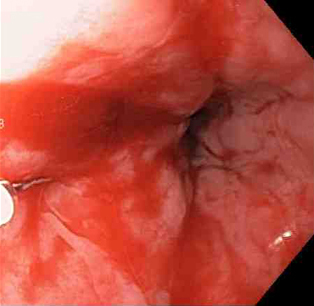

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Adrenaline is injected locally around the site of the Mallory-Weiss tearFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Actively bleeding tear appears as a red longitudinal defect with normal surrounding mucosaFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Actively bleeding tear appears as a red longitudinal defect with normal surrounding mucosaFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A through-the-scope clip deployed in the centre of the lesion (no previous adrenaline was infused in this case)From the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A through-the-scope clip deployed in the centre of the lesion (no previous adrenaline was infused in this case)From the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-bleeding adherent clotFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Non-bleeding adherent clotFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three haemoclips deployed to complete closure of the mucosal defectFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three haemoclips deployed to complete closure of the mucosal defectFrom the collection of Juan Carlos Munoz, MD, University of Florida [Citation ends].

NICE recommends giving a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) post-endoscopy to patients with stigmata (a visible vessel and adherent blood clot) of recent haemorrhage shown on endoscopy; however, NICE does not make a specific recommendation on the preferred route of administration or dose.[36] Follow your local protocols for advice on regimens.

Note that European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines recommend high-dose PPI post-endoscopy for all patients who receive endoscopic treatments.[35]

Practical tip

Remember to use the Rockall score post-endoscopy.[36] [ Rockall Score for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

A score of ≤2 is associated with a low risk of further bleeding or death.

A plan, based on the Rockall score, should be in place in case the patient starts bleeding again.

Patients who rebleed after endoscopic and medical treatments may need emergency surgery or interventional radiology to control the bleeding.[35][36] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK recommends:[36]

Repeat endoscopy for patients who rebleed with a view to perform further endoscopic treatment or emergency surgery

Interventional radiology for unstable patients who rebleed after endoscopic treatment. Refer the patient urgently for surgery if interventional radiology is not promptly available

Repeat endoscopy, with treatment as appropriate, for all patients at high risk of rebleeding, particularly if there is doubt about adequate haemostasis at the first endoscopy.

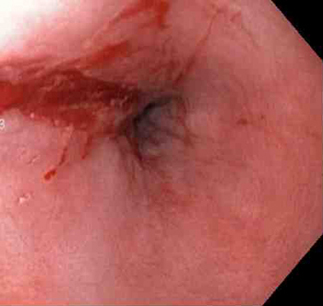

Rebleeding occurs in about 8% to 15% of patients, usually within the first 24 hours and most often in patients with high-risk factors for rebleeding, including:[84]

Age >65 years

Haematemesis and/or haematochezia at presentation

Haemodynamic instability/shock

Alcohol-use disorder

Aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use

Multiple blood transfusions

Comorbidities (anaemia, chronic liver disease, coronary artery disease, COPD, renal failure)

Actively bleeding lesions. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bleeding Mallory Weiss Tear viewed on retroflexionFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mallory Weiss tear after application of through-the-scope clip results in haemostasisFrom the personal collection of Douglas Adler; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer